Wright Was Right Captain For Mets But New Biography Doesn't Have The Same Power

BASEBALL IS MAKING A MISTAKE PLACING SO MANY EX-PLAYERS IN TV BOOTH

Pregame Pepper

Did you know ...

Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan played for all four original expansion teams: the New York Mets, Houston Astros (nee Colt .45s), Los Angeles Angels (then called California Angels), and Texas Rangers (originally the second-edition Washington Senators).

Timeless Trivia

After entering the 2020,playoffs with the worst rotation ERA of any playoff team in baseball history, Atlanta swept the first two rounds by holding opponents scoreless in 46 of 49 innings, giving the Braves the best team earned run average ever posted in a single postseason.

Leading Off

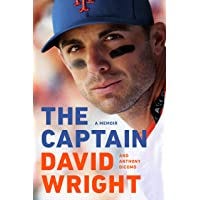

David Wright’s new memoir captures some of his career, but not enough

By James Schapiro

Understand this: I’m the biggest David Wright fan I know. Growing up, I played third base and wore number five. For my 16th birthday, my parents gave me a David Wright game model A2K. In college, I had a cardboard cutout of Wright’s face on my wall.

So imagine what it takes for me to say this: David Wright’s memoir is just okay.

The Captain, scheduled for release October 13th, is an interesting enough read for Mets fans. Wright tells some interesting stories, looks inside the Mets clubhouse, and describes his thoughts during some of his most memorable moments. At times, it’s funny, endearing, and profound.

But too often, it’s not. Too often, it slips into page upon page of exposition, reading like a summary of Wright’s Baseball-Reference page. When it’s good, it’s really good. But that doesn’t happen enough.

Injuries and comebacks are the defining feature of Wright’s career. The Captain, at least, captures these moments well.

Wright’s comebacks were also the reason he became my favorite player. In 2009, at age 12, I was diagnosed with pediatric epilepsy. My life changed. Even once I reached high school, I couldn’t drive or stay out late; I certainly couldn’t party. Each time I had a seizure, the restrictions were extended.

Meanwhile, also in 2009, Wright took a Matt Cain fastball to the head. He missed weeks with a concussion, and when he came back, he was shaken. “Stepping back into the batter’s box, I couldn’t shake that Little League mentality of bailing out on inside pitches,” he writes.

Wright and I healed together. Almost every summer, I had another seizure and Wright recovered from another injury. His 2015 recovery, in particular, brings out excellent writing. “Each Monday, I met with Dr. Watkins in his Marina del Rey office, hoping he might clear me for more intensive activities,” he writes. “Each Monday, he said no.”

It’s simple and to-the-point, and makes Wright’s emotions clear. It doesn’t mean much to write “I was frustrated.” It’s much more rewarding to understand the narrator’s frustration without being told.

The injury that really stands out to me, though, came in 2013. On August 2nd, as the Mets played the Royals, Wright was batting .309/.391/.512. In the tenth inning, he hit a slow ground ball, and sprinted down the line, trying for an infield hit. Sure enough, Wright beat the throw — and strained his hamstring as he crossed first base.

Too often, though, Wright does the opposite of what gives the book its best moments. Instead of showing, he tells. He slips into generic description, and leaves out the illustrative details.

Nowhere is this more obvious than Wright’s narration of game five of the 2015 World Series. Down three games to one, the Mets led in the ninth, but on a grounder to third, Eric Hosmer, representing the tying run, sprinted home as Wright threw to first. The Royals won three innings later.

Here’s how Wright tells the story:

“The Royals managed to tie the game off Matt (Harvey) and Jeurys Familia. They won it in twelve innings, celebrating on our field as our fans went home unhappy.”

That’s it. The biggest Mets moment of the decade is reduced to two lines that anyone who watched the game could have written.

This problem is compounded by another factor: Wright doesn’t want to scandalize. He won’t complain or rant; he’s almost absurdly respectful. Consider his treatment of Mets nemesis Chase Utley:

“I had a lot of respect for Utley’s hard-nosed style, which I considered similar to mine,” Wright writes. “Like me, Utley was a loyal player who really cared about winning.”

And his social life? It’s just as you’d imagine it.

“Despite New York’s temptations, I wasn’t much of a partier or a drinker,” he writes. “I didn’t spend my nights seeking out hot clubs or dates with celebrities or anything like that. I was never going to get caught doing something unsavory on TMZ or ‘Page Six’ in the New York Post. A lot of what some people enjoy about the city was lost on me.”

Wright’s stories just aren’t shocking or surprising. Even in the chapter called “adult stuff,” it turns out he’s just talking about negotiating his first contract.

The best moments of the book come in the final chapters, as Wright works toward one last return to the field. His voice becomes sharper; his memories get more specific. Suddenly, the book shines.

The night before Wright’s final game, I took the train from Providence, where I was in my senior year of college, to New York. I had three tickets to the game, for me, my girlfriend, who was flying in from Michigan, and my brother. The next day, we got to Citi Field hours early. With Wright’s career nearly over, I’d found a new favorite active Met: Brandon Nimmo, an always-smiling outfielder who got on base like he was born to do it. But Wright would always be my favorite.

Wright walked in the first. In the fourth, he fouled out. He’d been scheduled to take two at-bats and then depart, so that, we assumed, was that.

Sure enough, in the fifth, after Wright took the field, Mets manager Mickey Callaway came out to pull him. As the “Captain America” theme played, Wright waved to the crowd, hugged his teammates, hugged his coaches, waved again...then walked off the field, down the dugout steps, and up the tunnel to the clubhouse.

The game stayed scoreless for far too long, but finally, in the 12th, the Mets won on Austin Jackson’s walk-off hit. They celebrated on the field. Wright led the charge.

The play that really stands out to me, though, came in the seventh. Long after Wright had left the game, Brandon Nimmo came to bat. His .404 OBP was the highest full-season mark for a Met since Wright’s .416 in 2007. Leading off the inning, Nimmo singled to right — and pulled his hamstring as he crossed first base.

James Schapiro is a freelance sports reporter. His writing has appeared in Baseball Prospectus, The Delacorte Review, and Elite Sports NY. He writes the blog Shea Bridge Report. Follow him on twitter @jschapiro_SBR.

Cleaning Up

Please, MLB: Bring Back Local Team Announcers To Postseason Broadcasts

By Dan Schlossberg

During the Good Old Days of broadcast baseball, the World Series announcing teams always included one broadcaster from each of the two contestants.

That was a great idea – especially considering how poorly the so-called “national announcers” have been handling their postseason assignments.

Matt Vasgersian, who bounces around networks almost as often as Edwin Jackson changes teams, has a great voice but needs a fact-checker more urgently than candidates in political debates.

If he wanted to learn the correct pronunciation of Travis d’Arnaud’s surname, for example, all he had to do was listen to an inning or two of any Atlanta Braves broadcast.

He also needs to know that d’Arnaud was never traded from the Dodgers to the Braves but to the Tampa Bay Rays, where he spent all of the 2019 season before Atlanta signed him as a free agent – after they failed to land first choice Yasmani Grandal.

Vasgersian has a great voice and a plesant demeanor in the booth but he’s often surrounded by former players, managers, or even general managers who seem uncomfortable behind a microphone. They also sound uncomfortable.

Sometimes, it seems they don’t even know what they’re watching. In Thursday’s NLDS finale between Miami and Atlanta, Fox Sports announcer Adam Amin (who?) said “Ground ball to Acuna” even though the ball was hit to second baseman Ozzie Albies. Ouch!

With few exceptions, such as John Smoltz, Jim Kaat, and even newcomer Adam Wainwright, players don’t make good announcers. Many of them, especially Harold Reynolds and Bill Ripken, are truly awful and difficult to listen to.

When the FS1 image conked out during one of the Braves-Marlins games, I ran upstairs to catch the MLB Network broadcast on Sirius XM. As expected, the “local” Atlanta announcers were far superior to the national guys.

The reason is obvious: they see the team every day, know the participants, and know the history of the men and team involved, not to mention the history of the game.

One established baseball writer, auditioning for MLB Network, lost his bid for a berth because Reynolds did not realize Ted Williams was once a promising pitcher.

Williams once struck out 17 men while pitching for his San Diego high school team – there’s even a picture of him pitching in his autobiography – but Reynolds had no knowledge of it.

Instead, he challenged the auditioning writer, who had said that Williams, along with Babe Ruth and George Sisler, might not have been discovered as a hitter had the designated hitter rule come along decades sooner.

Reynolds is the only announcer, national or network, who persists in whistling as if he were sitting in the stands. It is not just annoying but ear-splitting and totally unprofessional.

MLB Network, like MLB teams, needs coaches: one to improve broadcast techniques, one to keep anchors well-versed in baseball history, one to provide instant fixes that should be corrected on-air, and another to make sure anyone assigned to a particular series knows as much about the teams involved as the local broadcasters.

That’s exactly why adding team broadcasters to postseason crews would be the best way to improve the quality of network broadcasts (are you listening, ESPN?).

Stuffing a room full of former players is simply not the best way to serve your audience.

HERE’S THE PITCH Weekend Editor Dan Schlossberg is former AP Broadcast Editor for New Jersey and host of a podcast called BRAVES BANTER. His e.mail address is ballauthor@gmail.com.

.