Pregame Pepper

Did you know…

The longest trio in one broadcast booth was not Keith, Ron, and Gary, still together after 17 seasons with the Mets, but Pete Van Wieren, Skip Caray, and Ernie Johnson, together for an amazing 33 years with the Atlanta Braves . . .

Attention, base-stealers: the larger bases being introduced this year decrease the distance between bases by 4 1/2 inches . . .

Members of the Yankees rotation already stymied by injuries are Frankie Montas, probably out for the year after shoulder surgery, and Nestor Cortes, who has a low Grade 2 hamstring strain in his right leg.

Montas, 29, is a free agent after this season . . .

Yankees ace Gerrit Cole has made the most starts of any pitcher since 2017 . . .

Erstwhile Mets ace Jacob deGrom, now with Texas, already has injury worries, with tightness on his left side . . .

Mike Trout, captain of Team USA, is scheduled to leave Angels camp March 6 to participate in the World Baseball Classic for the first time. He said he might be eased into action early in the tournament but is excited to play . . .

Promising prospect Garrett Mitchell is Milwaukee’s new center fielder . . .

Shintaro Fujinami, signed out of the Japanese leagues, is no Shohei Ohtani but still promises to prove a major help to the rebuilding of the rotation by the lame-duck Oakland A’s.

Leading Off

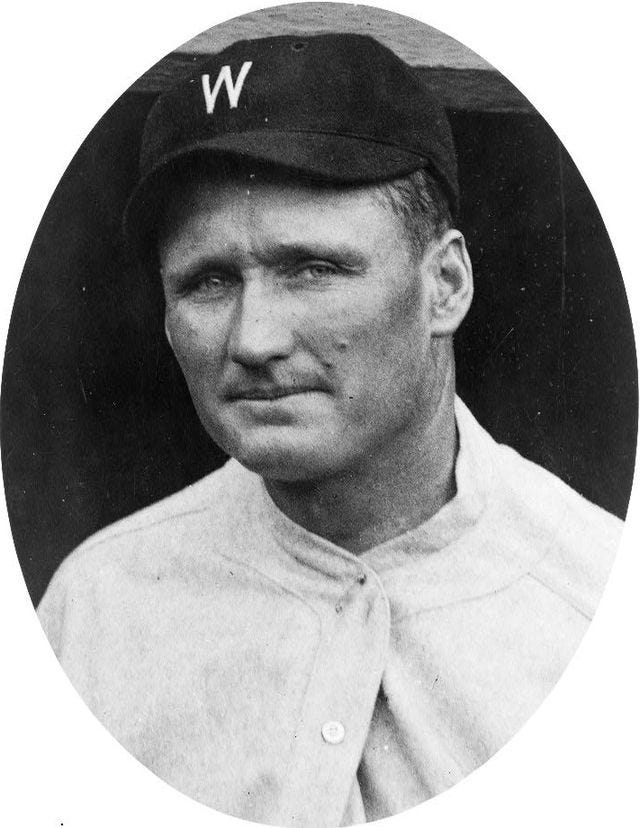

Walter Johnson, George Washington and the Rappahannock

By Andrew C. Sharp

Next to the apocryphal story about George Washington and the cherry tree, the most famous tale told about the Father of Our Country involves what he threw across the Rappahannock River. It was even alluded to on the icon Beach Boys’ album, All Summer Long, in 1964.*

Unlike the essential details of young George chopping down his father’s cherry tree, the story about Washington’s mighty heave has been passed down over years full of a variety of different accounts, starting with the event itself. Nobody knows when it happened or even what Washington is supposed to have thrown from the river banks. Some sources say he did it when he just 11 years old. Many people who have heard the story believe he threw a silver dollar clear across the much wider Potomac River.

Silver dollars were not minted as U.S. currency until 1796, but so-called Spanish dollars and colonial dollars were around when Washington was a younger man. The grandson of First Lady Martha Washington wrote that a young George Washington had thrown a piece of slate across the river.

In any case, on February 22, 1936 – the 204th anniversary of Washington’s birth -- Walter Johnson successfully threw two silver dollars across the Rappahannock. He did it at a spot that was part of Washington’s boyhood home near Fredericksburg, Va., close to where young George supposedly had done it.

Johnson’s effort drew national attention, including CBS radio coverage and front-page stories in hundreds of newspapers. He had been enlisted to try to duplicate Washington’s feat as part of a larger day of events commemorating the first president’s boyhood at a farm on the banks of the Rappahannock.

Johnson, less than a year after he resigned as manager of the Cleveland Indians, had just been selected as one of the first five inductees into baseball’s new Hall of Fame. The winter of 1936 was the first time since he reached the majors that he wasn’t preparing to head to spring training.

Officials in Fredericksburg apparently invited Johnson to their planned festivities and, thanks to Representative Sol Bloom of New York, head of the George Washington Bicentennial Commission, Johnson’s planned toss became the center of attention.

Bloom was a great champion of Washington but firmly believed that the cherry tree and Rappahannock tales where fictions that somehow diminished the memory of the first president. Bloom offered 20-to-1 odds that Johnson would not be able to throw a silver dollar to the river’s opposite bank.

The catch, it turned out after $5,000 was deposited to take up him up on those odds, was that Bloom insisted that 18th-century maps depicted the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg to be more than 1,300-feet wide -– farther than Washington or anyone could throw a coin. City officials dismissed that claim about the river’s width.

Johnson visited the spot where his throw was to be made and determined he might be able to do it. He began practicing at his Germantown, Md., farm. He wrote in a message to Fredericksburg officials, “I am practicing with a dollar against my barn door. Arm getting stronger, barn door weaker.”

People in Fredericksburg, who were told the river there was 372 feet wide, began trying without success to do it with lead washers. It turned out the distance from one bank to the other where Johnson’s throws were made was actually 272 feet.

On a typically cold winter day, Johnson was ready to give it a try. Crowds, estimated at a few thousand to 10,000 depending on the source, gathered on both side of the river. With $100 promised to the person who retrieved the official silver dollar, more folks gathered on the opposite side from Johnson and the official entourage.

Johnson first toss fell several feet short, but his second clearly made it to the other side. He then said he was ready to throw the official inscribed silver dollar. The Big Train threw it well into the crowd on the opposite side. A 31-year-old stone mason, called Peter Yon in most accounts but Pietro Yon in the next day’s New York Times, ended up with the coin.

Many people told reporters they believed Johnson’s toss lent credence to the George Washington story. Bloom was good-natured about it, but remained unconvinced and refused to pay off any bets.

Whether Washington did it or not, Walter Johnson on February 22, 1936, became forever part of the story.

* "Our Favorite Recording Sessions" -- Brian Wilson: "Hey, will you take off that hat? You look like George Washington!" Mike Love: "I'll throw you across the river.... I threw a silver dollar across; I can throw you."

Andrew C. Sharp is a retired daily newspaper journalist and a SABR member who has written several dozen BioProject and Games Project essays. He blogs about D.C. baseball at WashingtonBaseballHistory.com

Cleaning Up

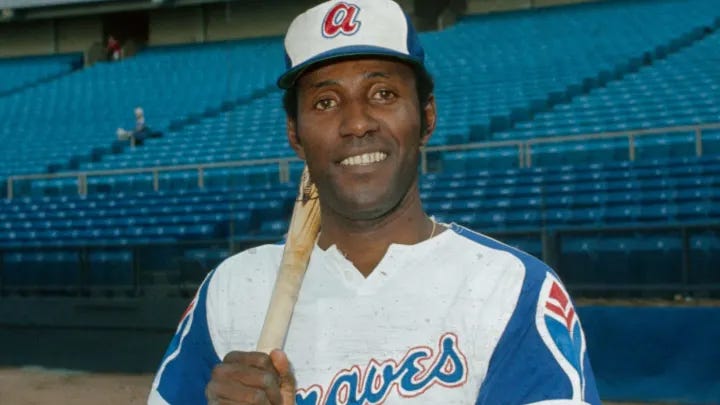

Rico Carty Was A Colorful Character In So Many Different, Often-Difficult Ways

By Dan Schlossberg

Let’s start with his lyrical name: Ricardo Adolfo Jacobo Carty.

Then there was his nickname: the Dominican slugger, in deference to his Caribbean accent, called himself “the Beeg Boy.”

To most people in baseball, he was simply Rico.

It was 60 years ago that he broke into the big leagues — beeg leagues in his jargon — with the Milwaukee Braves. The team already had future Hall of Famers Hank Aaron, Eddie Mathews, Joe Torre, and Warren Spahn but none had an ego as big as the rookie Dominican.

Rico was right about one thing: he could hit. Anyone, anytime, anywhere.

In 1964, his official first year, he gave Dick Allen a spirited run for the National League’s Rookie of the Year award.

Five years later, he hit .342 with a .401 on-base percentage but was foolishly left off MLB’s computerized All-Star ballot for 1970. Voting fans were paying attention, however, and made him the first write-in candidate to win a starting berth in the game.

Carty continued to impress, winning the NL batting title with a .366 mark, coupled with a .454 on-base average, .584 slugging percentage, and 1.037 OPS. Still unappreciated, however, the slugging left-fielder finished only 10th in the MVP voting.

Carty copied four of his uncles, accomplished Dominican boxers, when he battled with Aaron aboard the Braves team plane in 1972. The pushing-and-shoving match reached its climax when Carty called Aaron “a black son-of-a-bitch” and Henry responded with a cool but classic line: “You’re not exactly pink yourself.”

Carty, whose complexion was much darker than Aaron’s, had been a popular player among Braves fans. But the fight changed all that.

The team had no choice but to dump him, landing only a forgettable Texas Rangers pitcher named Jim Panther.

That started a Carty odyssey that led through Cleveland, Toronto, Oakland, and the North Side of Chicago in addition to Texas. He did reach a career peak in home runs when he hit 31 for the ‘78 Blue Jays but Carty was more of a line-drive hitter anyway.

He finished at .299 with 204 career home runs but hit .300 on the nose (with no home runs) during the first NL Championship Series, against the 1969 Miracle Mets.

Although the fans loved his smile and outgoing personality, coaches and managers found Carty difficult. Although he would have made a perfect designated hitter, the DH didn’t arrive in baseball until 1973.

That left Carty stranded in left field — the safest position to hide the defensively-challenged slugger. Bobby Bragan, hired to manage the team in 1963, thought moving him behind the plate would force Carty to pay more attention. You can look it up: Carty actually caught 17 games for the Milwaukee Braves in 1966.

Maybe Bragan knew Carty had caught for the Dominican team in the 1959 Pan-Am Games, when he played so well that eight teams offered him contracts. Carty, confused, signed them all, forcing Milwaukee to do some maneuvering to keep him.

Carty’s career was pockmarked with injuries and incidents.

He missed two full seasons — one with tuberculosis and another with a leg injury — and also punched a heckler, tangled with policemen, criticized managers, and complained that he didn’t play enough, although the Braves had to squeeze Felipe Alou, Lee Maye, Mack Jones, and Carty into two positions. No one was going to challenge Aaron’s playing time.

At 6’3” and 200 pounds, Carty was a mass of muscle — he maintained his form from his amateur boxing days — but was also a massive headache on and off the field. If not for his obvious ability to hit, he never would have lasted so long.

But, like Julio Franco years later, he was a well-sculpted Latino who loved the game and never wanted to quit. He played winter ball in his native country annually and, at age 49 in 1988, led the Dominican team to a third-place finish in the first Men’s Senior Baseball League World Series. Using a wooden bat, he also won a home run contest in the 40-plus age bracket.

He retired as the Dominican League’s all-time home run king with 59, though that record didn’t last. Enshrined in two Halls of Fame, honoring heroes of Caribbean Baseball and Latino Baseball and is even an honorary general in the Dominican army.

Not bad for a kid from San Pedro de Macoris who grew up with 15 brothers and sisters.

Now 83, Rico still lives in the Dominican. And reports say he can still swing the bat.

Former AP sportswriter Dan Schlossberg of Fair Lawn, NJ remembers watching Rico Carty play for the Braves in Milwaukee and Atlanta. He covers baseball for forbes.com, Latino Sports, Memories & Dreams, USA TODAY Sports Weekly, Sports Collectors Digest, and Here’s The Pitch. E.mail Dan via ballauthor@gmail.com.

Timeless Trivia

“I’m not thinking he can do the job, I know he can do the job. But he has to come up in here and he has to win a job. We’re not giving him anything. We just tried to get him ready to compete, and he’s ready to compete.”

— Braves third base coach Ron Washington on new shortstop Vaughn Grissom

After making two starts in 2022 because of three non-arm-related injuries, Red Sox southpaw Chris Sale, a walking injured list since closing out the 2018 World Series for Boston, has announced that “Humpty Dumpty got put back together,” and proclaimed himself 100 per cent healthy . . .

Detroit’s Spencer Turnbull, who threw a no-hitter in Seattle on May 18, 2021, hopes to prove he’s recovered from the Tommy John elbow surgery he underwent three weeks after his gem . . .

Also looking healthy again is Angels third baseman Anthony Rendon, a former NL RBI king held to 105 games by injuries over the last two years . . .

Lefty reliever Sean Doolittle, now 36, is back with the Nationals after undergoing an experimental alternative to Tommy John surgery . . .

Fernando Tatis, Jr. missed all of 2022 (fractured wrist, PED suspension) and will switch from shortstop to right field when he’s eligible to return April 20 . . .

From Mark Bowman of MLB.com: “When the Dodgers were at Vero Beach, they had first-class dining options for their employees, visiting team executives, scouts and media members. You could find steak, pasta, salads and great desserts.

“Well, [Dave] O’Brien and I went through the cafeteria line and found a table in the corner. Did I mention each table was adorned with a nice white tablecloth? Our tablecloth remained clean until I dropped some spaghetti. No big deal, right? Wrong. A few minutes later, an attendant approached us and said that table was reserved for Tommy [Lasorda]. We got up and left the spaghetti-stained cloth for Tommy.”

Know Your Editors

HERE’S THE PITCH is published daily except Sundays and holidays. Brian Harl [bchrom831@gmail.com] handles Monday and Tuesday editions, Elizabeth Muratore [nymfan97@gmail.com] does Wednesday and Thursday, and Dan Schlossberg [ballauthor@gmail.com] edits the weekend editions on Friday and Saturday. Readers are encouraged to contribute comments, articles, and letters to the editor. HTP reserves the right to edit for brevity, clarity, and good taste.

I loved the Braves TBS crew.

https://powderbluenostalgia.substack.com/p/the-superstation-effect