The Forever Connection Between St. Louis and Stan Musial

Today, we look at the deep and strong relationship between a city and a baseball legend.

IBWAA members love to write about baseball. So much so, we've decided to create our own newsletter about it! Subscribe to Here's the Pitch to expand your love of baseball, discover new voices, and support independent writing. Original content six days a week, straight to your inbox and straight from the hearts of baseball fans.

Pregame Pepper - Stan The Man

Leading Off

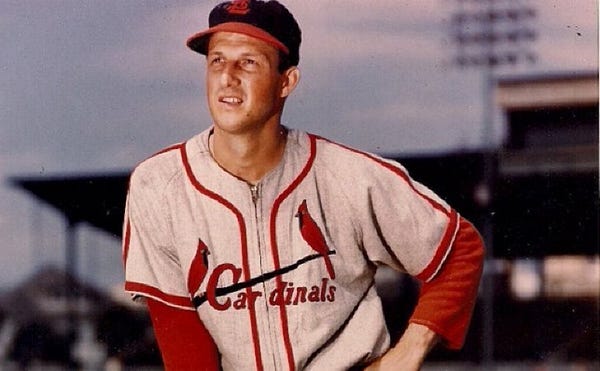

The Symbol of St. Louis: Stan “The Man” Musial

By Bill Pruden

Albert Pujols’s late-season renaissance served as a reminder of a now-distant era of major league baseball history. It was not so much the way the Hall of Fame-bound slugger performed as it was the way the city embraced the man whose best years had been achieved while wearing a St. Louis Cardinals uniform.

Indeed, in a time before free agency, the way Pujols finished his career, both in style and in the same uniform he had started it in, embraced by the fans and the city he had so impressively represented, was the norm—although without the detours that marked Pujols’s journey—something that was, in its own way, a central part of the bond between a team, its fans, and their shared city. It was part of what made baseball the national pastime. But it was a different time, one before free agency, when the early years of a player’s career were the time when the relationships were nurtured and developed and were not simply an extended audition prior to the bidding war to come when free agency arrived.

I harbor no ill will towards the modern players who, finally out from under the reserve clause, have taken advantage of the market value of their talents. And yet Pujols’s return was an illuminating reminder of the often-forgotten relationships and of the ties that were for so long central to fans, cities, their teams, and the game itself.

Interestingly, in that now all but forgotten time no one embodied that civic connection more than Pujols’s Cardinals predecessor Stan Musial. His nickname, Stan “The Man,” said it all. While it originated in the frustration of Brooklyn Dodgers fans who in 1946, bereft over their team’s inability to get Musial out, started to chant “Here comes the man again,” during a game at Ebbets Field, it became something more. Indeed, after St. Louis Post-Dispatch writer Bob Broeg heard it he included it in a story, and as one writer put it, “the man” became “The Man.” And over the course of the 22 seasons he played with the Cardinals it was a title he embodied in full. And yet for all his baseball heroics and accomplishments—and they fill pages of the game’s history books—it was in the way Musial went about his business, the kind of person, teammate, and friend he was, that he was truly “The Man.”

Certainly, it was a fitting moniker for a player whose name remains high on virtually every major list of offensive achievements that the Major League record books track. But it speaks loudest to the way he carried himself, and the way he represented the Cardinals and the National League at a time when only half the nation was able to see him play during the regular season. Happily, Musial’s status as the leader, along with Hank Aaron and Willie Mays, in All-Stars game appearances, allowed the denizens of many American League cities to see the best the National League had to offer.

Indeed, Musial’s baseball accomplishments were legendary, and featured a lifetime batting average of .331, with 3,630 hits. He won three Most Valuable Player Awards and was the leader of three World Series championship teams, something nobody, not even a member of the New York Yankees, could boast about during the 1940s and 1950s. And the list goes on, accomplishment after accomplishment, an unimagined happy ending for a guy who thought his baseball dream had died in 1940 when the aspiring pitcher injured his shoulder, diving for a ball in the outfield. But supported by his manager, one-time White Sox pitching star Dickie Kerr, Musial demonstrated a determination and resilience that would characterize his career and his character, remaking himself into one of the most feared hitters the game has ever seen.

Indeed, it was an approach that never changed. Curt Flood recalled that when he was traded to the Cardinals from the Cincinnati Reds, Musial helped keep his spirits up as he tried to find his place on his new team. But no less importantly, Flood also remembered the quiet inspiration Musial provided. Flood remembered clearly how despite his stature as an established superstar, Musial worked endlessly on his swing. Flood recalled thinking that if the immortal Musial was working that hard, he could give nothing less.

Some sportswriters said that when Ty Cobb retired from baseball he left the game with more money but fewer friends than anyone else ever had. Conversely, Musial was said to have left with more friends than anyone before him. It was an apt remark about a man whose friends ranged from the fan in the street to the man in the White House - after an introduction from a local St. Louis pol, President John F. Kennedy presented Musial with a PT-109 pin, and the two men were reported to be genuinely friendly. And yet, in the end, it was the average fan, his teammates, and the people of St. Louis, his neighbors, with whom the harmonica-playing Musial was most comfortable.

Two years ago today, on the 100th anniversary of his birth, an article on Musial noted that late in his life there had been an increasing number of books and articles on the St. Louis icon that included stories that simply were not true. And yet as the author noted, no one cared because Musial in fact was as good as the myth.

Indeed, the notoriously combative Bob Gibson, a teammate in Musial's final seasons, once observed that Musial was the "nicest man I ever met in baseball. And, to be honest, I can't relate to that." But the competitive Gibson could certainly relate to the man who Ty Cobb once called “the closest to being [a perfect ballplayer] in the game today... He plays as hard when his club is way out in front as he does when they're just a run or two behind." It was simply who he was.

The recognition of that stature did not end when his playing days were over. Indeed, generations later, when Pujols left the Cardinals and joined the Angels in 2012, the Angels greeted his arrival by placing billboards around Southern California welcoming Pujols and referring to him as "El Hombre," Spanish for “The Man.” Pujols was not pleased and made clear that in his view, there was only one baseball player deserving of the moniker, “The Man,” St. Louis icon Stan Musial. Indeed, not long after Musial’s death, Pujols observed, "I wish my kids had the opportunity to be around him because that's how I want my kids to live their lives. I want them to be like Stan Musial. Not the baseball player. The person."

The person who made every effort to attend the Hall of Fame ceremonies where his harmonica playing was guaranteed to bring smiles to the faces of his baseball brethren. The person who helped rookies and veterans alike and who never forgot a friend. Indeed, “The Man” who, while doing all he could to avoid having it come to light, had, upon hearing that his old manager, mentor, and friend, Dickie Kerr was experiencing tough times, bought Kerr and his wife a house in Houston. A Houston sports writer ultimately found out about it and the news spread but for Musial, it was simply a thank you to a most special friend.

There can be no denying that Stan Musial came from another time, and in many ways, Albert Pujols reminded us that you can still be loved in a city without spending your whole career there, and yet the longevity and the dedication it reflects, coupled with character, can make for something special. And that something, especially as embodied in the iconic life of Stan “The Man” Musial, offers any baseball fan something to think about as the hot stove league begins and the free agent derby gets underway. The relationship--between a player, his team, the fans, and the city--cannot be quantified. Scott Boras can’t put it in one of his famous binders, and neither the Yankees nor the Dodgers can write a check for the appropriate amount, but it does matter, and that is worth remembering—and not just in the baseball world.

Bill Pruden is a high school history and government teacher who has been a baseball fan for six decades. He has been writing about baseball--primarily through SABR-sponsored platforms, but also in some historical works--for about a decade. His email address is: courtwatchernc@aol.com.