IBWAA members love to write about baseball. So much so, we've decided to create our own newsletter about it! Subscribe to Here's the Pitch to expand your love of baseball, discover new voices, and support independent writing. Original content six days a week, straight to your inbox and straight from the hearts of baseball fans.

Pregame Pepper

Did you know …

A first-time candidate has been elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame for seven years in a row . . .

There were 21 women in MLB on-field coaching or player development positions in 2020 . . .

Actors Jon Hamm and John Goodman both root for the St. Louis Cardinals . . .

Lou Whitaker and Jackie Robinson are the only second basemen in baseball history who are 200 batting runs, 50 fielding runs and 25 base-running runs above average.

Leading Off

Lifetime Tenure, Lifetime Fans: Baseball and the Justices of the Supreme Court

By Bill Pruden

On January 20, Chief Justice John Roberts will administer the oath of office to President-elect Joe Biden, marking the start of a new presidential term. In so doing, Roberts will be making a rare appearance outside the cloistered confines of the Supreme Court. But despite the Justices’ public invisibility, one place that they can often be found is at the ballpark.

The Court has historically boasted a lineup of passionate baseball fans.

Its long history with the game made headlines in 1922 with a ruling in Federal Baseball Clubs v. National League. That case, which held that the Sherman Antitrust Act did not apply to Major League Baseball, proved central to the game’s ongoing operations.

The exemption was reaffirmed in the Court’s 1953 ruling in Toolson v. New York Yankees. And, of course, there was its 1972 decision in Flood v. Kuhn, which, although affirming the reserve clause, nevertheless represented the beginning of the end of baseball as it was then known. The reserve clause was abolished soon afterward and the financial dynamics between players and owners were forever altered.

For many, it was the Flood case, especially Justice Harry Blackmun’s opinion, which first alerted the public to the Justices’ love of baseball. In fact, the first part of the opinion shined a spotlight on the Court’s veneration of the game and its players for it was, as super-fan Blackmun himself acknowledged, an ode to baseball’s history. And anyone--lawyer or layman--who read it, could not miss the deep personal connection to the game that many of the Justices have had. Indeed, the connections made clear that despite their high office, the Justices were just quintessential Americans in love with the national pastime.

Those personal connections went back at least to the start of the 20th Century and Theodore Roosevelt appointee Justice William R. Day. A member of the Court for almost two decades beginning in 1903, Day is regularly included on the lists of the Court’s most fervent fans. That status might have resulted from his practice of regularly leaving the Court after oral arguments and heading straight to the ballpark to catch that day’s Washington Senators game.

Chief Justice William Howard Taft, who as president inaugurated the tradition of the season-opening first pitch, was a dedicated fan during his tenure on the Court during the Roaring Twenties. So too was Chief Justice Fred Vinson, who served from 1946-1953. A star at Centre College and in semi-pro leagues, Vinson turned down a try-out with the St. Louis Cardinals, opting instead to focus on pursuing a legal career, but his love for the game never waned.

Nor did it for many others. Justice William J. Brennan Jr., an ardent fan, delighted in recalling his introduction to the Court and his fellow members. According to Brennan, on his first day, Chief Justice Earl Warren, himself known for periodically taking his clerks to games, brought Brennan into a conference room. Flipping on the light, the pair found the rest of their brethren huddled around the television watching the opening game of the 1956 World Series. A quick set of introductions was followed by a call to turn out the lights so that the nation’s top jurists could return to the Fall Classic.

One of Brennan’s long-time colleagues also included on the list of the Court’s most diehard fans was Potter Stewart, who served from 1958 to 1981. Stewart reportedly offered numerous additions to Blackmun’s biographically-oriented historical tribute in the Flood opinion. The Cincinnati native’s love of baseball was later recalled in a eulogy delivered by fellow Yale alum George H. W. Bush, a baseball fan himself. The 41st president, who captained the 1947 and 1948 Yale baseball teams that were runners-up in the inaugural College World Series, happily memorialized Stewart’s life-long allegiance to his hometown Reds.

But Bush failed to remind the audience of the famous note passed among his brethren by that same Justice Stewart during oral arguments on October 10, 1973. The historic note had two important bits of information: “V.P. Agnew just resigned !!” and “Mets 2, Reds 0” in the NLCS.

The current Court has a strong complement of fans, too. By most accounts, the most rabid is Justice Samuel Alito. Following his nomination by President George W. Bush, who previously owned the Texas Rangers, it was a rare news profile that failed to mention Alito’s passion for the Philadelphia Phillies.

His attendance at a Phillies Fantasy Camp was a clear indication of the depth of his love for the National League club — not to mention publication of pre-confirmation photos of a star-struck Alito meeting Jim Bunning, then a U.S. Senator from Kentucky but previously a Hall of Fame pitcher for the Phillies. Alito’s reaction to Bunning’s memorabilia-lined office represented every encounter between a fan and the hero he idolized. Among that memorabilia were items from the 1964 Father’s Day perfect game Bunning, a father of nine, threw against the Mets at Shea Stadium. It remains an iconic Phillies moment.

Alito’s passion for the Phillies was acknowledged and celebrated by his new judicial teammates, who arranged for the Phillie Phanatic to be a surprise special guest at the traditional welcome party given to the Court’s newest member.

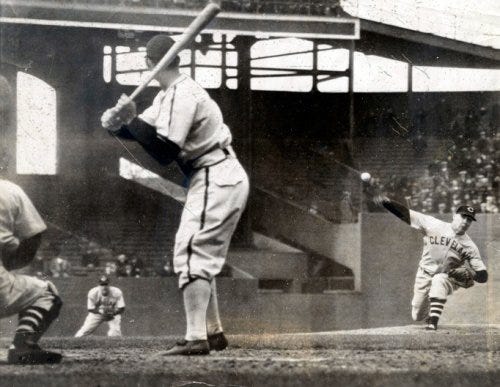

The Court Alito joined in 2005 already included a number of avid fans, but none greater than Chicago native John Paul Stevens. The Court’s then-senior justice was an avid Cubs fan and his chambers featured a framed scorecard from Babe Ruth's famous “Called Shot” game, which Stevens had attended.

He reveled in throwing out the first pitch at a 2005 Cubs game and was grateful to be able to live long enough to see the Cubs finally win the World Series in 2016, a victory made all the sweeter by his attendance at Game Four in Wrigley Field. So recognized was his devotion that the Cubs Twitter account acknowledged his death when the 99-year-old jurist passed away in 2019.

Speaking of throwing out the first pitch, it increasingly seems to be a perk of the job for those who are interested. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, whose ruling as a District Court judge in 1995 ended the 1994 strike and earned her the title “The judge who saved baseball,” has done the honors in both leagues.

Her first turn came in Yankee Stadium for her beloved Bronx Bombers (a devotion that led President Barack Obama to kid that Sotomayor had ordered a pinstriped judicial robe in anticipation of the addition of New York Mets fan Elena Kagan to the Court). She later took the mound before a Washington Nationals game in late September 2019 as the team was barreling toward the post-season and an improbable World Series win.

Justice Alito would show that same judicial evenhandedness, performing the task with a pitch before a Phillies game before crossing over to the American League and a Rangers contest.

Even those who are not zealous fans understand the connection of baseball with the American populace. It was likely no accident that in his 2005 confirmation hearing, now Chief Justice John Roberts, explained his approach to judging by drawing upon baseball. He unequivocally asserted that “Judges are like umpires. Umpires don’t make the rules, they apply them. The role of an umpire and a judge is critical…but it is a limited role.” He also noted that “Nobody ever went to a ball game to see the umpire” and then promised, “I will remember that it's my job to call balls and strikes and not to pitch or bat.”

In its own way, it was a pointed tribute to the game as well as a reminder of its centrality to the American experience. That fact probably explains why baseball is referenced, alluded to, and analogized more than any other sport in Court decisions. But in the end, it is the game itself to which the justices, and all others, return, for it is the distinctive time-honored game, and the players who have written its history, that makes us fans.

While the stories are many and the love of the game real, it is perhaps appropriate to close with a quick look at a man whose ties to the game were long and varied, Justice Arthur Goldberg. A Chicago native, Goldberg, who also served as Secretary of Labor and UN Ambassador, always said that the best of his many youthful jobs had been manning a coffee urn at Wrigley Field, a post ideally suited to watching his beloved Cubs. Years later it was Goldberg who argued on behalf of Curt Flood before a Court that still included his former colleagues and fellow fans Brennan and Stewart.

But two years earlier, while running for Governor of New York, Goldberg took a break from the campaign trail by taking in a Mets-Cubs game at Shea Stadium. The skepticism about politicians being what it is, Goldberg’s appearance raised questions about his bona fides as a fan, but those who knew the former justice quickly attested to his passion. But while his candidacy led him to reference his Cub loyalties in the past tense, when he got to the stadium, his true colors emerged as he asked if he could get his picture taken with Mr. Cub, Ernie Banks.

Meanwhile, during the game, Goldberg found himself under siege from one of his companions, reporter Jimmy Breslin, who kept badgering the candidate about the issue of drug addiction. An exasperated Goldberg was heard to ask, “What'd we bring him for? I want to watch the game.”

And so it goes. Whether a Justice or a juvenile, in the end, a fan just wants to enjoy that most American of experiences. We all just want to watch the game.

Bill Pruden is a high school history and government teacher who has been a baseball fan for over half a century and a student of the Supreme Court since his days in law school left him more interested in the Justices than in the work they did. He has been writing about baseball--primarily through SABR sponsored platforms, but also in some historical works--for about a decade. His email address is courtwatchernc@aol.com.

Cleaning Up

Close But No Cigar: These Hurlers Knocked On Door Of 300 Club

By Dan Schlossberg

Only 24 pitchers in baseball history won 300 games.

It’s not easy. Think of the math: a player needs to average 15 years of 20 wins or 20 years of 15 wins.

No wonder nobody’s done it since 2009 and nobody’s on the horizon — especially in an era of five-man rotations, strict pitch counts, and few complete games.

A bunch of others could have vaulted over the 300-win plateau but missed for one reason or another.

Bob Feller, who finished with 266 victories, was stopped by wartime military service in the U.S. Navy. He won eight battle stars for his work as a gunner on the U.S.S. Alabama during World War 2 but ran out of time in his trek toward 300.

Asked years later if he had any regrets, he told me, “I didn’t win 300 but we did win World War 2 and that was probably more important.” Probably?

Tommy John had a longer career — 26 years — but needed a year off for the elbow ligament surgery that was later named after him. He wound up with 288, a dozen short of the golden number that almost certainly would have punched his ticket for Cooperstown. “I’d rather be in the Hall of Fame than have a surgery named after me,” he admitted in a private conversation.

Fellow lefty Jim Kaat’s nemesis was neither war nor injury but a manager who wanted a situational southpaw for his bullpen. Tony La Russa, returning to the managerial ranks this year at age 76, was the guy who took a durable starter and assigned him to the bullpen for the last four years of his career. Aided enormously by his ability to hit and field, Kaat won 283 times. But he fell 17 short of that “automatic” ticket to the Hall of Fame gallery.

Like Kaat, Ferguson Jenkins missed the magic number because he too was marooned in the bullpen — early in his career. But Jenkins, with 284 wins, eventually reached the Hall of Fame gallery.

So did Bert Blyleven, who had 287 wins, and Robin Roberts, with 286. Both missed 300 because they pitched for teams that couldn’t score.

“If you follow the game,” Blyleven said, “you know how difficult it is for a pitcher to win. Everything has to go your way. I lost 250 games in my career but a lot of them were close. If I lost 1-0 I thought it was my fault. It made me work harder.”

Blyleven had 20 no-decisions in 1979 and more 1-0 victories than anyone not named Grover Cleveland Alexander. “I knew I was 13 short of 300,” said Blyleven, who threw 60 shutouts, “but if you include my Little League wins, I’m well over. I went as far as my body could take me. When my mind and body told me I couldn’t go nine anymore, I knew it was time to do something else.”

John wanted to hang on and tie Ryan’s record of pitching for 27 years. “I definitely wanted to get there,” he said, “but nobody would sign me. I sent tapes to the Cardinals and Orioles, telling them I would start or relieve. [Cardinals manager] Whitey Herzog wanted me but [GM] Dal Maxvill said, ‘Why would you want an old guy like that when we can utilize the younger pitchers from our organization?’”

John won just one fewer game after returning from elbow surgery than Sandy Koufax won in his whole career. But Koufax, whose arthritic elbow forced his premature retirement, is in the Hall of Fame.

“He struck out a lot of guys and his wins were more spectacular,” the former pitcher said, “but a win is a win. The guys I played with and against who saw me pitch know how well I did. Just look at the record.”

Roberts, who once went 28-7 and twice topped 30 complete games, had a 1-10 mark for the abysmal 1961 Phillies, a team that finished last. He later pitched better for the Cubs, Orioles, and expansion Colt .45s. But it was too late to get to 300.

Jenkins, like John, was a victim of his own age. “I thought about winning 300 for quite a few years,” he said, “and was hoping to have that chance with the Cubs. I went to spring training in 1984 at the invitation of Dallas Green. There were 15 younger pitchers and me. It came down to a numbers crunch. I did fairly well but they wanted some of the younger guys to get a better shot. I decided it was time to retire.”

That same year, Kaat went to spring training with the Pittsburgh Pirates. “My career was over but Chuck Tanner thought I could still pitch,” he revealed. “I had a pretty good spring but when you’re 45 and they have young prospects, your chances are slim. I wanted to give it one last fling and it was fun anyway.”

Among the pitching legends who never reached the 300 Club — or even came close — were Bob Gibson, Juan Marichal, Don Drysdale, Whitey Ford, and Jim Palmer.

No active pitchers have much of a shot either, according to The Bill James Handbook 2021.

Justin Verlander, out with Tommy John surgery, will be 39 years old and 74 wins short before he pitches again. Zack Greinke, 37, is 92 victories away. Max Scherzer, 36, and Clayton Kershaw, 33, have both won 175 games. Jon Lester has 193 but he’s 37.

Dan Schlossberg of Fair Lawn, NJ is the author of The 300 Club: Have We Seen the Last of Our 300-Game Winners? He’s also weekend editor of HERE’S THE PITCH, national baseball writer for forbes.com, and columnist for Ball Nine. Dan’s e.mail is ballauthor@gmail.com.

Timeless Trivia

MLB postponed 40 games because of COVID-19 outbreaks in 2020 . . .

Before rules were changed during the season, a doubleheader with two nine-inning games was played on July 28 . . .

Although he led the Giants to three world championships, manager Bruce Bochy had a losing record (1052-1054) with the team . . .

In 2020, Yankees DJ LeMahieu and Luke Voit were the first teammates to lead their league in batting and home runs since Hank Aaron and Eddie Mathews of the 1959 Milwaukee Braves.

________________________________________________________________

Know Your Editors

HERE’S THE PITCH is published daily except Sundays and holidays. Brian Harl [bchrom831@gmail.com] handles Monday and Tuesday editions, Elizabeth Muratore [nymfan97@gmail.com] does Wednesday and Thursday, and Dan Schlossberg [ballauthor@gmail.com] edits the weekend editions on Friday and Saturday. Readers are encouraged to contribute comments, articles, and letters to the editor. HTP reserves the right to edit for brevity, clarity, and good taste.

_________________________________________________________________________