IBWAA members love to write about baseball. So much so, we've decided to create our own newsletter about it! Subscribe to Here's the Pitch to expand your love of baseball, discover new voices, and support independent writing. Original content six days a week, straight to your inbox and straight from the hearts of baseball fans.

Pregame Pepper

Did you know…

The career of Jose Abreu seems over, as the Cuban first baseman has been released by the Houston Astros at age 37. A former MVP and three-time All-Star, he had hoped a trip to the low minors (Class A West Palm Beach) would energize his lost power . . .

Thinking out loud here, suppose the pitching-hungry Astros and hitting-hungry Braves traded expiring contracts: third baseman Alex Bregman for starting pitcher Max Fried . . .

Houston has been hammering by pitching injuries, with almost an entire starting rotation on the IL except for ancient ace Justin Verlander . . .

The Los Angeles Dodgers are still hot to trot for a shortstop, hoping to move Mookie Betts back to second, where he’s better defensively . . .

Looking forward to the telecast of the first major-league game from Rickwood Field, last bastion of the Negro Leagues and the oldest ballpark (1910) still in use . . .

Jason Jennings of the Colorado Rockies remains the only pitcher in modern era big-league history to throw a shutout and hit a home run in his debut (in fact, he went 3-for-5 that night). He only hit one other home run — and it was the only one hit by an opposing pitcher against Hall of Famer Greg Maddux (who gave up 352 to position players) in a career that stretched for 23 seasons.

Leading Off

Do more stolen bases assure winning baseball?

By Andrew Sharp

Stolen-base attempts have increased the past two seasons after several years of historic lows. As expected, restrictions on the positioning of infielders and on pickoff attempts have increased the number of successful stolen-base attempts.

So it’s unlikely steals ever again will drop to the level of the 1950s, even if a low total of steals hasn’t always kept teams from successful seasons.

Since 1901, when the American League entered the scene, 11 teams have failed to steal even 20 bases in a season. The lowest total ever was 13 by the 1957 Washington Senators.

In just 51 attempts all season, Washington base runners were thrown out 38 times trying to steal. Either the opposing catchers were especially good, or the Senators were lacking in speed and/or managerial daring. Given that Washington fired manager Chuck Dressen after a 5-16 start and eventually lost 99 games, you can safely draw your own conclusions.

This futility on the bases and last-place finish was quite a comedown from the franchise that in 1913 had 287 steals, one short of the A.L. record and total that was not topped for 63 years.

The 1950s were the nadir in the history of stolen bases in the major leagues. The percentage of steals per game has been less than 0.3 only six times since 1901, five of those between 1950 and 1956. The other time was 1949. A May 14, 2022, New York Times article contrasted those numbers with the 1987 average of 0.85 steals per game and the percentage from 2018 to 2021 – just under 0.5 per game.

It’s hardly a surprise that 10 of the lowest 21 team totals come from the 1950s. Add 1949 and 1960, the total is 12 of 21. The 1958 Senators stole just 22 bases -- tied for the 15th lowest total. That team also finished last. So did the 1960 Kansas City Athletics, second with the fewest steals after Washington with 16.

Yet a near-record low total did not automatically doom a team in the standings. Winning teams and bad teams are equally represented among those that stole the fewest bases.

Playing 162 games, the 1972 Tigers stole just 17 bases, tied for the third-worst all-time, but still won their division. The 1949 St. Louis Cardinals just missed the N.L. pennant, winning 96 times and finishing a game behind the Dodgers. Like the Tigers, those Cards stole 17 bases -- in just 30 attempts. The Dodgers, in contrast, led the league with 117 steals, 69 more than any other team.

The 1953 Cardinals won 83 games and finished in third place. They made just 40 steal attempts, making it safely 18 times, tied for sixth lowest (the 1949 and 1953 Cards had different managers). The 1934 Yankees has just 19 stolen bases but won 94 games, finishing second.

The ’53 Browns, in their final season, lost 100 and finished last. They also had just 17 steals. Between them, the two St. Louis teams stole 35 bases in 1953. No Lou Brock there.

A rule change in 1920 no longer awarded steals for what today is considered defensive indifference – let them do it -- so some stolen-base totals from the dead-ball era probably are somewhat inflated.

Before Babe Ruth, steals were a key part of scoring. Then slugging became the more common way to generate offense. Although annual totals fluctuated a bit, the trend was down through the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s.

A paucity of hitting in the mid and late 1960s could be a factor in the resurgence of stolen base totals then. Brock’s success and that of the Oakland A’s in general surely contributed to the 1970s’ upward trends that continued through the ’80s.

Ty Cobb’s 1915 dead-ball era record of 96 steals stood until 1962 when Maury Wills stole 104 bases for the Dodgers. Brock topped Wills with 118 in 1974. Rickey Henderson’s record of 130 in 1984 still stands, Cobb’s 1915 mark has been topped nine times now, but not since 1987.

Washington’s 287 steals in 1913 were as one less than the A.L. record 288 in 1911 by the soon-to-be Yankees. The Senators finished second with 90 wins; New York finished at .500 in sixth place.

The 1976 Athletics set the new standard with 341 and finished second in the West with 87 wins. Bill North (75), Bert Campaneris (54), and slugger Don Baylor (52), led the way. Soon after, Henderson arrived.

The ’50s Senators never had a major stolen base threat, but they did have two players with the worst success rates among those with 10 or more attempts: Pete Runnels was 0 for 10 in 1952, and Eddie Yost was safe just once in 11 attempts in 1957.

En route to the Baseball Hall of Fame, Luis Aparicio led the league in steals for nine consecutive seasons. The first three times were emblematic of the era: His totals were 21 in 1956, 28 in ’57 and 29 in ’58.

Yet the lowest total in each league for an individual leader in steals –- 16 by Stan Hack in the N.L. in 1938 and 15 in the A.L. by Dom DiMaggio in 1950 –- likely will be more than the 1957 Senators’ paltry team total for years to come.

Andrew Sharp is a retired journalist and a member of SABR. He blogs about D.C. baseball at washingtonbaseballhistory.com. Email comments to andrewcsharp@yahoo.com.

Cleaning Up

Bad-News Braves Can’t Even Beat The Bad Teams

By Dan Schlossberg

In baseball, the way to sew up a pennant is to beat the bad teams and play .500 against the contenders.

Apparently, the Atlanta Braves forgot that time-tested adage.

All of a sudden, they’re easy prey for the Washington Nationals, the team universally picked to finish last in the National League East.

After losing six of their eight games against the Nats this season, however, the Braves are actually closer to third-place Washington than they are to first-place Philadelphia.

When the week started, Atlanta owned a record of 35-28, a winning percentage of .556, and a second-place standing (nine games behind) that is shrinking more quickly than Tom Hanks in Big.

Washington was 30-35, 15 games behind, but just six behind Atlanta after winning three times in four-game sets on consecutive weekends.

For the Braves, who started the season as prohibitive favorites to extend their best-in-baseball streak of six straight division titles, Murphy’s Law has enveloped the ballclub. And we don’t mean two-time MVP Dale Murphy, the would-be Hall of Famer whose continued exclusion from Cooperstown remains an agonizing oversight.

Aside from rejuvenated DH Marcell Ozuna, who has taken over the coveted three-hole in the batting order, the entire lineup is not just cold but frigid.

None of the eight Atlanta All-Stars sent to Seattle last summer is holding his head above the ice.

Catcher Sean Murphy suffered an oblique injury Opening Day, missed the first two months, and seems lost at the plate since returning.

The entire infield of Austin Riley, Orlando Arcia, Ozzie Albies, and Matt Olson is fumbling in the field and embarrassing themselves at the plate, flailing to reach pitches well out of the strike zone, rarely walking, and producing only sporadic power.

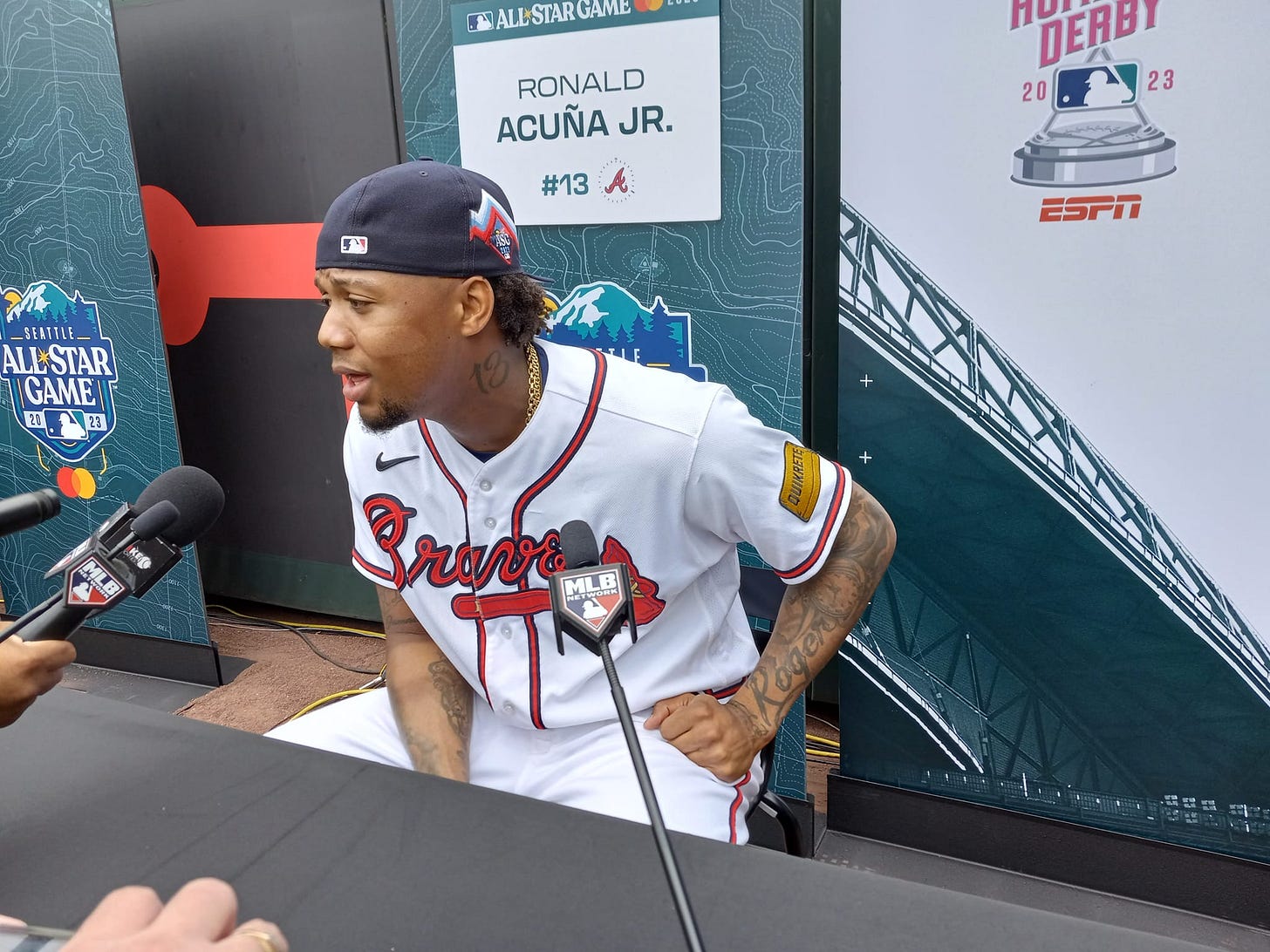

Outfielders Adam Duvall, Michael Harris II, and Jarred Kelenic aren’t much better. Nor was defending MVP Ronald Acuna, Jr., whose knee problems cost him two weeks of spring training and culminated in a torn ACL — ending his season early for the second time in four years.

Losing the leadoff man, who was coming off the only 40/70 season in baseball history, hurt. But losing center-fielder Michael Harris II and star pitcher Spencer Strider hurt more.

Harris, a Gold Glove contender, suffered a hamstring injury running the bases last night and has been placed on the 10-day IL, likely to be replaced by former Oakland standout Ramón Laureano, who’s been tearing it up for Triple-A Gwinnett after starting the season in a funk for Cleveland.

Strider’s 20 wins and 281 strikeouts led both leagues last year and he looked even better during the spring after unveiling a baffling breaking pitch that had batters totally off-balance.

Two starts into the season, however, his right arm started barking — forcing him to the injured list for the duration after an elbow brace procedure.

While remaining starters Max Fried, Chris Sale, and Reynaldo Lopez have all pitched their way into serious All-Star consideration, Charlie Morton has thrown like the 40-year-old he is, looking especially bad against Washington for reasons unknown.

Worried about keeping their top starters sharp all season, manager Brian Snitker has given them extra rest, trying to fill the gap with a parade of Not Ready For Prime Time Players.

The Braves have received less than a handful of solid starts from a revolving fill-in corps that has included Bryce Elder, Ray Kerr, Spencer Schwellenbach, AJ Smith-Shawver, Darius Vines, Hurston Waldrep, and Allan Winans. Never mind that Elder was an All-Star last year or that all of the others arrived with enormous expectations (which turned out to be little more than hype).

It won’t be long before the Braves again give the ball to Jesse Chavez, along with Morton the National League’s other 40-year-old pitcher (only American Leaguer Justin Verlander, 41, is older). The bespectacled Chavez, serving as a long man in the Braves pen, throws strikes and gets outs, as his record entering the week shows (1-1, 1.37 in 20 games and 26 1/3 innings) indicates.

Righting the ship won’t be easy. It’s not age — Olson is the oldest regular at 30 — or money — every key position player has a comfortable long-term contract.

Could it be complacency?

The 2023 Braves led the majors in wins (104), home runs (307), and slugging (.501), sharing and setting major-league marks in the last two categories. Five players topped 30 homers and three (Olson, Ozuna, and Acuna) topped 40, a feat originally accomplished by the Braves trio of Hank Aaron, Davey Johnson, and Darrell Evans in 1973.

Maybe it’s time to retool, recalling fleet outfielder Forrest Wall from Gwinnett, putting him at the top of the lineup, and reinstalling the left-right platoon of Kelenic and Duvall in left field. Having a base-stealer at the top could change the entire offense, as Acuna proved while setting a club record in steals (73) last summer.

Snitker has stuck stubbornly to the same lineup rather than shake things up, give his regulars a breather, or change the batting order. Nor has the stoic manager held clubhouse meetings.

But he hasn’t seen his team play this poorly since he succeeded Fredi Gonzalez as interim manager in 2016.

Before the season becomes a blemish on his record, it’s time to try something radical.

Former AP sportswriter Dan Schlossberg of Fair Lawn, NJ is the author of Home Run King: the Remarkable Record of Hank Aaron and 40 other baseball books. His email is ballauthor@gmail.com.

Timeless Trivia: More on the Bad-News Braves

“Obviously, there’s frustration. But you’ve got to keep your spirits up. We feel like, and know, we’re a better team than what we’ve done as of a late. But baseball is a crazy game. Sometimes it can flip on a dime. All we can do is show up every day and work, and trust that (the day it flips) is today or tomorrow.”

— Atlanta slugger Matt Olson on the team’s unexpected nose-dive in the NL East

With their loss to Baltimore Tuesday plus a Phillies win, the Braves fell a full 10 games behind first-place Philadelphia in the National League East — their largest deficit since the start of play on June 2, 2022, when they trailed the Mets by 10 1/2 games . . .

After avoiding a shutout since May 12, 2023 –- a span of 182 games and 390 days –- Atlanta suffered two in six games during the road trip that ended yesterday . . .

Sean Murphy’s 392-foot fly-out at Camden Yards Tuesday would have been a three-run homer in every other park but was an out at Oriole Park because the left-field fence was moved back 26 feet before the 2023 season . . .

Until light-hitting Baltimore shortstop Jorge Mateo connected with two men on in the second inning of the same game, Max Fried had never yielded a home run on an 0-2 breaking ball . . .

After starting the season 18-6, the Braves went 17-23 . . .

Atlanta has less than 100 games remaining but has made up a double-digit deficit before, most remarkably in 1993 when chasing and catching the San Francisco Giants in the National League West title chase (that’s no typo — the team was stuck in the wrong division for 25 years until the NL split into its current three-divisional format).

Know Your Editors

HERE’S THE PITCH is published daily except Sundays and holidays. Benjamin Chase [gopherben@gmail.com] handles Monday and Tuesday editions, Elizabeth Muratore [nymfan97@gmail.com] does Wednesday and Thursday, and Dan Schlossberg [ballauthor@gmail.com] edits the weekend editions on Friday and Saturday. Readers are encouraged to contribute comments, articles, and letters to the editor. HTP reserves the right to edit for brevity, clarity, and good taste.