Maybe Marty Marion ISN'T a Hall of Famer

PLUS: CHISOX ARE (THANKFULLY) WRAPPING HORRENDOUS CAMPAIGN

IBWAA members love to write about baseball. So much so, we've decided to create our own newsletter about it! Subscribe to Here's the Pitch to expand your love of baseball, discover new voices, and support independent writing. Original content six days a week, straight to your inbox and straight from the hearts of baseball fans.

Pregame Pepper

Did you know…

In the biggest regular-season game of his life, Max Fried blanked Kansas City for 8 2/3 innings last night as the Braves won, 3-0, and moved closer to the playoffs. In 8 seasons in Atlanta, the stone-faced southpaw went 72-36 with a 3.10 ERA, 854 strikeouts, Cy Young runner-up in 2022, and World Series ring.

Congrats to Yankee sluggers Aaron Judge and Giancarlo Stanton, who homered in the same game Thursday for the 14th time — tying the single-season club record of Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris in 1961 . . .

Among the 15 rookie Tigers who have turned the team into a playoff contender are third baseman Jace Jung, shortstop Trey Sweeney, and catcher Dillon Dingler . . .

Hard to believe the budget-conscious Bengals unloaded Jack Flaherty, Mark Canha, Andrew Chafin, Carson Kelly, and Gio Urshela since the trade deadline . . .

Detroit was sinking fast in the AL Central with a 55-63 record August 10 before blooming into a ballclub with the most wins in baseball since . . .

Cleveland All-Star Steven Kwan, normally a contact hitter, was batting .352 at the break but has been flirting with the Mendoza Line ever since . . .

No closer has won a Cy Young in 21 years but Cleveland’s Emmanuel Clase has a strong case . . .

Choosing the NL Rookie of the Year will be tough with Paul Skenes, Jackson Chourio, Jackson Merrill, Spencer Schwellenbach, and Shōta Imanaga all strong contenders.

Leading Off

Is Marty Marion A Hall of Famer?

By Paul Semendinger

Two weeks ago, I wrote an article that showed that between 1960 and 1985 most players who finished in the Top 10 of vote-getters for the Hall of Fame eventually earned enshrinement into the hallowed halls of Cooperstown. The most notable exception to that rule was Marty Marion, who finished among the Top 10 no fewer than eight times but never received enough votes to gain entry into the Hall of Fame. No player in that period finished so high in the Hall of Fame voting so often and failed to gain entry.

I began to wonder if Marty Marion belongs in the Hall of Fame...

In this day and age, most Hall of Fame arguments begin with WAR. Unfortunately, many of the arguments also end with WAR. For many fans, and baseball writers, if a player's WAR isn't high enough, he isn't a Hall of Famer. For many, WAR makes a cut-and-dry case. To those in the WAR camp, a score of 60 or better signifies that a player is Hall of Fame worthy. None of that bodes well for Marty Marion's Hall of Fame case.

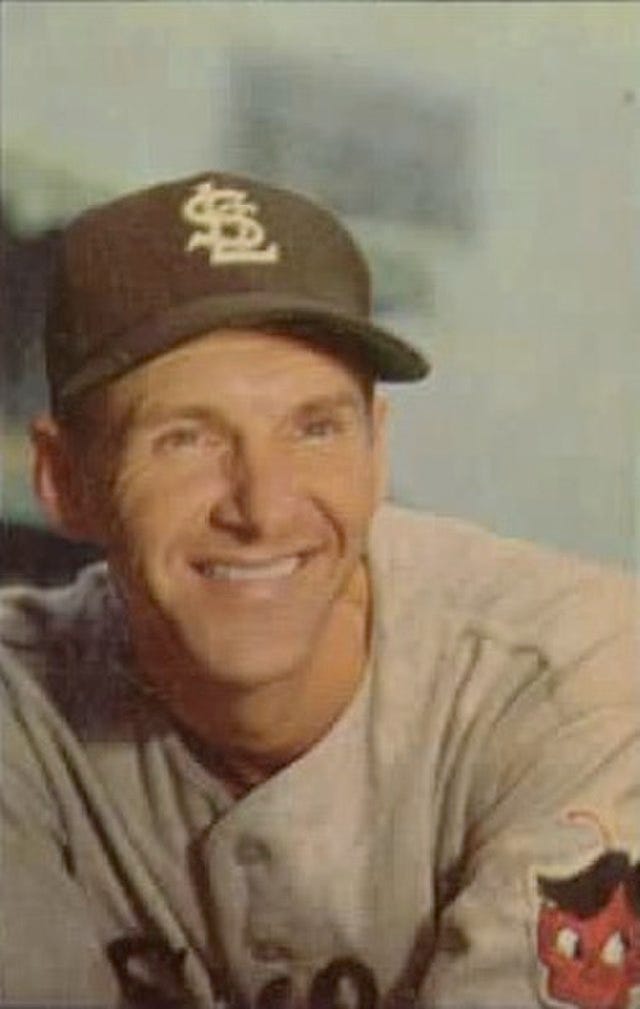

Marty Marion was a standout defensive shortstop who was not much of a hitter. Marion's lifetime batting average was an unimpressive .263. Marion never hit .300 in any season. He never hit even .290.

Marion's best batting average for any season was .280. Marion also didn't hit for power. He hit just 36 homers in his career. Marion didn't drive in runs, totaling just 624 runs batted in. All of these low numbers drag down Marion's lifetime WAR to an unimpressive 31.8. Among all-time shortstops, Marion ranks #69 all-time.

I believe WAR is a great starting point for a Hall of Fame discussion. I do not believe it is the be-all and end-all. But, a WAR of 31.8 doesn't even seem to be in the ballpark for Hall of Fame consideration. Still, I wanted to dig more deeply.

Marion's great skill was with his glove. In his day, he was considered the game's best- fielding shortstop. Some said that he was possibly the greatest fielding shortstop of all-time. His defense was instrumental in helping his team, the St. Louis Cardinals, reach four World Series (winning three of them) between 1942 and 1946.

Marion's defense was so impressive that he was selected the National League's Most Valuable Player in 1944. Marion was also seen as a leader on the diamond.

In his career, Marion earned MVP votes in seven different seasons, including six consecutive times from 1941 through 1946. In his day, he was considered one of the best, as the MVP votes seem to prove.

What hurts Marion's Hall of Fame case is the fact that his playing career wasn't very long. He played 13 seasons in the big leagues, but only 11 as a starter.

For players with shorter careers, there usually needs to be a standout feature to their play to help propel them into the Hall of Fame. For Marion, that standout feature is his defense but, unfortunately, defense is still very difficult to quantify. The numbers don't seem to bear this out. It can be said that Marty Marion was a great fielder, but in his career, he never led the league in chances, putouts, assists, or double plays.

It seems, then, that Marion's Hall of Fame case rests upon his leadership and the perception of his defense. Other glove-first shortstops from his relative era who were also on frequent pennant-winners, such as Pee Wee Reese and Phil Rizzuto, are in the Hall of Fame. With this, though, we come back to WAR.

Reese, not much of a hitter, had a WAR of 68.4 (14th all-time among shortstops), while Rizzuto compiled 42.2 WAR (41st all-time among shortstops).

Rizzuto's case (based just on WAR) is weak, at best, but still his performance was miles ahead of Marion's. Another glove-first shortstop, who was also a St. Louis Cardinal, was Ozzie Smith, who had a WAR of 76.9. Smith ranks eighth all-time among shortstops.

All three of those shortstops had careers much more noteworthy than Marion.

As I considered Marty Marion's case, I decided to go in one other different direction — All-Star games.

In his 11 full seasons, Marion was selected to eight All-Star contests. That alone sounds impressive, but I wondered if it really is.

I made a list of the eligible players who have not reached the Hall of Fame but who have the most All-Star appearances.

Heading that list are players excluded from the Hall of Fame for well-documented reasons: Pete Rose (17), Barry Bonds and Alex Rodriguez (14), Mark McGwire and Manny Ramirez (12), and Roger Clemens (11).

Next, though came some border-line players: Bill Freehan (11), Steve Garvey (10), plus Elston Howard, Dave Concepcion, Fred Lynn, Frank McCormick, and Gary Sheffield (9 each).

There are a host of players with eight All-Star games, like Marion, who are not in the Hall of Fame. This standard also does not help Marty Marion's case.

One name on the All-Star list that stands out is Dave Concepcion. On the surface, he seems like a good match for Marty Marion. Both of those players were glove-first All-Star shortstops on teams that were multiple-time champions.

I thought also of Bert Campaneris. Campy was in seven All-Star games.

Again, unfortunately, for Marion, when comparing him to Concepcion and Campaneris, two similar-type players, he comes up wanting.

While WAR isn't everything, it does serve as a guide. Both Concepcion and Campaneris are miles ahead of Marion.

Concepcion's lifetime WAR of 40.1 ranks 45th all-time. Campaneris was much more impressive (even with one less All-Star appearance) with a WAR of 53.0, good for 22nd all-time. (Campaneris actually has an interesting Hall of Fame case himself.)

When one looks at the players most like Marty Marion, the case becomes crystal clear. Of the 10 players most similar to Marty Marion, only Leo Durocher is in the Hall of Fame. But he’s there as a manager, not a player.

The most similar player to Marion is Rafael Ramirez, who also isn't getting called to Cooperstown any time soon.

It seems that Marty Marion was an outstanding defensive shortstop who had an impressive career.

It also seems clear that while he was an excellent player, he wasn't a Hall of Famer.

Paul Semendinger was just elected Vice President of the Elysian Fields Chapter of SABR. Dr. Semendinger has written a number of books including From Compton to the Bronx (with Roy White), The Least Among Them, Scattering the Ashes, and 365.2: Going The Distance. Paul will be running the NYC Marathon to support the Sesame Workshop. You can donate to support helping to educate children today by donating here: https://fundraiser.sesameworkshop.org/2024-nyc-marathon-fundraiser/drsem?tab=MyPage

Cleaning Up

This Year’s ‘Black Sox’ Were Historically Bad

By Phil Coffin

The Chicago White Sox are wrapping up one of the worst seasons in Major League Baseball history. They were chasing the record for most losses in a season in the majors since the American League began play in 1901. And they will just miss becoming the team with the worst winning percentage in the modern game.

Here’s a look at the 10 worst teams in modern history, starting with the White Sox, how they got so bad and how long it took to recover.

2024 Chicago White Sox 39-121 .244

---

Like two of the other teams on this list, the White Sox have had recent success. In 2021, they won the American League Central Division in Manager Tony La Russa’s return to the South Side. But as analyst Joe Sheehan wrote in a recent newsletter, “It’s a collapse with few parallels in baseball history, and none where owner intent -- the 1910s A’s, the 2000s Marlins -- wasn’t part of the equation.”

The top players on the roster regressed, top prospects never stepped forward, and the 2024 team chased the 1962 Mets with none of the allure that was attached to the Amazin’s.

The White Sox’s best player was a 31-year-old pitcher, Erick Fedde, who the season before was playing in South Korea. Chicago dealt him to the Cardinals at the trade deadline.

Two seasons before: 81-81, 61-101

Best player (season): Erick Fedde, 31, pitcher, 4.7 bWAR

Best player (career): Mike Clevinger, 33, pitcher, 17.4 bWAR

1916 Philadelphia Athletics 36-117 .235

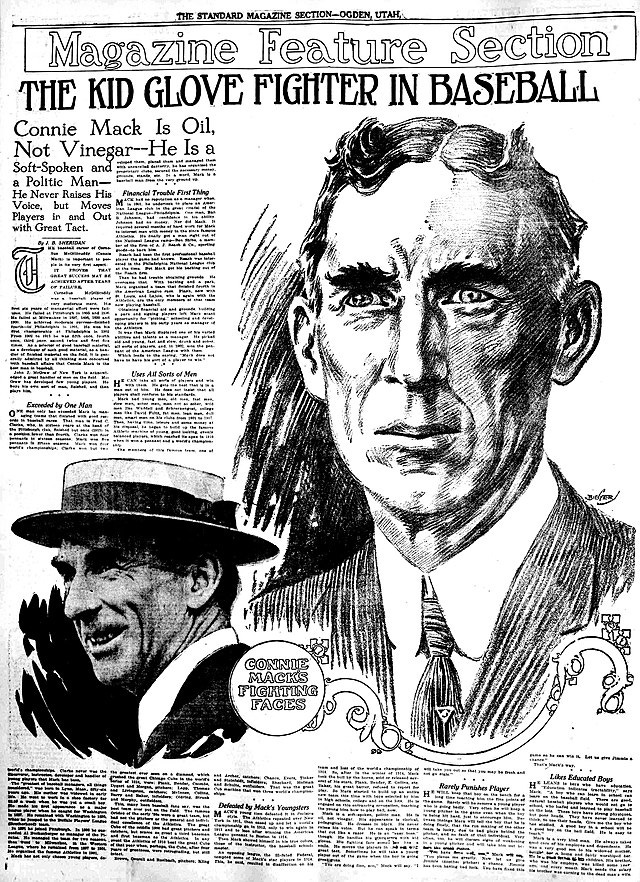

Connie Mack, owner and manager of the Athletics, constructed the American League’s first dynasty. From 1909 to 1914, the team averaged 97 victories and won four pennants and three World Series. But in 1914, Philadelphia lost the Series to the Miracle Braves and attendance plummeted nearly 40 percent as the AL and NL faced competition from the Federal League. While attendance sank, salaries spiraled upward, and Mack concluded he could no longer afford his star-laden roster. Gone were four future Hall of Famers (second baseman Eddie Collins, third baseman Home Run Baker and pitchers Eddie Plank and Charlie “Chief” Bender); after a 43-109 record in 1915, only the second losing mark in the team’s 15 seasons, the sell-off continued. What most likely looked like a historically bad .283 team in 1915 became the truly historically bad .235 team.

Two seasons before: 99-53, 43-109

Two seasons after: 55-98, 52-76

Next winning season: 1925 (88-64)

Best player (season): Amos Strunk, 26, center fielder, 4.1 bWAR

Best player (career): Napoleon Lajoie, 40, second baseman, 106.9 bWAR

1935 Boston Braves 38-115 .248

It took only three years for the 1914 Miracle Braves to fall from World Series champions to the second division. That’s where the Braves stayed until 1933, with only a single winning season in that stretch. By the time Boston began winning in ’33, buoyed by the power-hitting rookie outfielder Wally Berger, the team’s finances were in shambles, and by 1935, the team was Berger, Babe Ruth on his last legs and a bunch of nobodies. Berger led the National League in homers with 34 and RBIs with 130 (on a team that was last in the league in runs scored); the rest of the Braves hit only 41 homers and drove in 414 runs. Second on the team in homers was the 40-year-old Ruth, who played 28 games and homered six times as a drawing card who could no longer draw or hit.

Two seasons before: 83-71, 78-73

Two seasons after: 71-83, 79-73

Next winning season: 1937

Best player: Wally Berger, 29, center fielder, 5.8 bWAR

Best player (career): Babe Ruth, 40, 182.6 bWAR

1962 New York Mets 40-120 .250

Laugh at Marv Throneberry, face of the ’62 Mets, but he did have a positive Wins Above Replacement as calculated by Baseball Reference. OK, it was only 0.2, barely better than a replacement player, but it was positive. And the Mets led the league in drawing walks. But of the team’s four players with at least 2.0 WAR, only one was under 30 (25-year-old starter Al Jackson), and the six ex-Dodgers combined for a WAR of 2.5. The first season was hardly a fluke; the Mets lost at least 100 games in five of their first six seasons. But in season No. 8? They won 100 games and the World Series.

Two seasons before: None; expansion team

Two seasons after: 51-111, 53-109

Next winning season: 1969

Best player: Roger Craig, 32, pitcher, and Frank Thomas, 33, left fielder, 2.5 bWAR

Best player (career): Richie Ashburn, 35, center fielder, 64.2

1904 Washington Senators 38-113 .252

The professional teams in Washington had always been bad. Throughout the 19th century, no matter the league, no matter the name, Washington was a losing franchise. By 1899, the Senators capped a decade of losing in the National League with a 54-98 record, better than only the hapless Cleveland Spiders. The Senators were so lackluster that they were one of four teams contracted out of the league. They were resurrected as a charter member of the American League, and still they lost: 61-72 in their first season, and they just kept getting worse until they reached their 1904 nadir. They earned their record: last in runs scored, last in ERA. Two of their starters went 5-26 (Happy Townsend) and 5-23 (Beany Jacobson), but at least they had excellent nicknames.

Two seasons before: 61-75, 43-94

Two seasons after: 64-87, 55-95

Next winning season: 1912

Best player: Casey Patten, 30, pitcher, 3.7 bWAR

Best player (career): Patsy Donovan, 39, right fielder, 18.4 bWAR

1919 Philadelphia Athletics 36-104 .257

Philadelphia fans have the reputation for being impatient and unpleasant, but consider the disappointment that is in the city’s sporting DNA. Take these Athletics. As noted above, a sterling team was dismantled after 1914 for financial reasons, and the Athletics suffered 10 consecutive losing seasons. Connie Mack built another powerhouse and won two more World Series titles, only to dismantle the team during another financial crisis. After unloading Hall of Fame pieces, the Athletics had losing records every year from 1934 to 1946. It was no better across town, where the Phillies, after following up a 1915 World Series appearance with two more winning records, managed a single winning record in the next 31 seasons (and it wasn’t much of a winning record: 78-76). The losing was not confined to baseball: The Eagles had a losing record in their first 10 seasons in the NFL, beginning in 1933. They couldn’t creep above .500 until 1943, when they combined with the Steelers to become the wartime Steagles, with a 5-4-1 record. No wonder Philly fans can be surly.

Two seasons before: 55-98, 52-76

Two seasons after: 48-106, 50-103

Next winning season: 1925 (88-64)

Best player: Cy Perkins, 22, catcher, 1.4 bWAR

Best player (career): Jimmy Dykes, 22, second baseman, 34.8 bWAR

2003 Detroit Tigers 43-119 .265

Three years after the Tigers chased the Mets’ record for losses, they were in the World Series, an unprecedented turnaround for baseball’s biggest losers. The 2006 Tigers were unlike the 2003 team in almost every way. Of the regular nine-man lineup, only outfielder Craig Monroe remained in ’06. The Tigers had added a couple of stars, outfielder Magglio Ordonez and catcher Ivan Rodriguez, shortstop Carlos Guillen nearly matched his career-best season and DH Marcus Thames had a career year. On the mound, Jeremy Bonderman and Nate Cornejo, a combined 12-36 with an ERA above 5.00, had matured. But crucial improvement came from a 41-year-old veteran (Kenny Rogers) and a 23-year-old in his first full season (Justin Verlander). It also helped that the bullpen could hold a lead; the 2003 Tigers had 27 saves in all, while the 2006 team was led by Todd Jones, who saved 37 himself.

Two seasons before: 66-96, 55-106

Two seasons after: 72-90, 71-91

Next winning season: 2006 (lost in World Series)

Best player: Dmitri Young, 29, DH, 3.4 bWAR

Best player (career): Bobby Higginson, 33, right fielder, 23.1 bWAR

1952 Pittsburgh Pirates 42-112 .273

Murry Dickson had more WAR than any other player on the 1952 Pirates, but he was 35 years old and led the league in earned runs and home runs and was beginning a stretch of leading the NL in losses three consecutive years. The pitcher everyone wanted to see instead – no one more than Pirates management, including Branch Rickey – was a skinny 20-year-old who had walked 7.4 batters per inning the year before in Class D: Ron Necciai. “He had all the raw ability any pitcher ever had,” Rickey said. He started the 1952 season back in Class D, where on opening night he struck out 20 batters in a two-hit shutout. In his next start, Necciai struck out 19; three days after that, he fanned 11 of the 12 batters he faced in relief. That set up his May 13 start: 27 strikeouts (his 26th would have ended the game, but the third strike got away from the catcher and the batter reached base). He got one more start in Class D and whiffed another 24 batters. He received a promotion to Class B and then to Pittsburgh, in August. “He could be the answer to our prayers,” catcher Joe Garagiola said. He wasn’t; Necciai went 1-6 with a 7.08 ERA and walked 32 batters in 54 2/3 innings. He was overworked and underweight, thanks to ulcers, which only got worse after he was drafted into the Army. After a medical discharge, he was ready for a comeback, injured his shoulder and retired at age 23 in 1955, by which time the Pirates had improved only to a 60-win team. But by then the Pirates had found an answer to their prayers: a 20-year-old rookie outfielder named Roberto Clemente.

Two seasons before: 57-96, 64-90

Two seasons after: 50-104, 53-101

Next winning season: 1958

Best player: Murry Dickson, 35, pitcher, 5.2 bWAR

Best player (career): Ralph Kiner, 29, left fielder, 48.0 bWAR

1909 Washington Nationals 42-110 .276

By 1909, the team had become the Nationals, but one thing hadn’t changed: They still couldn’t win. Two years earlier, however, the Nationals had found a hard-throwing kid who had grown up on a Kansas farm and in the California oil fields: Walter Johnson. At age 21 he was not yet Walter Johnson – he went 13-25 with an ERA not a whole lot above league average – but the next year he was. Washington did not make such fortuitous player moves often enough, though; they let go of a 27-year-old part-time outfielder who had by then washed out with three AL teams. In his 30s, Gavvy Cravath went on to become the NL’s pre-eminent power hitter (aided, it must be said, by the forgiving dimensions of the Baker Bowl).

Two seasons before: 49-102, 67-85

Two seasons after: 66-85, 64-90

Next winning season: 1912

Best player: Walter Johnson, 21, pitcher, 3.8 bWAR

Best player (career): Johnson, 166.9 bWAR

1942 Philadelphia Phillies 42-109 .278

The Phillies were a quarter-century into their pit of losing seasons after this nightmare. They earned ignominy: The Phillies were last in just about every offensive and pitching category. The team’s owner, no surprise, wanted to sell, but he couldn’t find a buyer, so the National League took over the franchise. Years later, Bill Veeck said he wanted to buy that team and stock it with Negro league players – Jackie Robinson’s signing was still several years away – so this would have been a groundbreaking effort. Veeck said the commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, squashed the sale. But there is scant evidence that a sale to Veeck was ever contemplated. No Veeck, no integration – and for the Phillies, no quick path to winning. They didn’t break .500 until 1949. (And they didn’t integrate until 1957.)

Two seasons before: 45-106, 50-103

Two seasons after: 64-90, 61-92

Next winning season: 1949

Best player: Tommy Hughes, 22, pitcher, 3.3 bWAR

Best player (career): Chuck Klein, 37, pinch-hitter, 46.6 bWAR

1899 Cleveland Spiders 20-134 .130

What’s the difference between 1899 baseball and 1901 baseball that makes 1901 “modern”? In 1899, there was one major league, with 12 teams, some of which had owners – frequently called magnates by the press – that controlled two teams. By 1901, there were two major leagues and no syndicate ownership. Still, the 1899 Spiders are memorable for the worst season in major league history. The 1898 Spiders were a respectable 81-68, while the ’98 St. Louis Browns were 39-111. Two teams, same owners, who concluded that stacking the St. Louis franchise was the better play, so the Spiders were decimated. (For example, a midcareer Cy Young was “assigned” to St. Louis. So were six of the eight position players.) The Spiders, predictably enough, started off poorly, at 3-9, and then they became pathetic: 11 straight losses. The team’s longest winning streak was two games, on May 20 and 21, in a heady stretch in which it won four of six games. But by mid-June, the Spiders had added a 13-game losing streak. In the first game of a home doubleheader on July 1, the Spiders beat Boston, 10-9, to “improve” to 12-48 – a .200 percentage. They lost the second game, however, and then had to finish the season on the road because the rest of the league was frustrated that their cut of the Spiders’ paltry home attendance didn’t cover their costs. What followed was a 93-game road trip and an 8-85 record. Cleveland won only one of its final 40 games, sandwiching a 5-4 victory in 10 innings over Washington between losing streaks of 24 and 16 games. (The 24-game skid began with a loss that a newspaper account attributed to “stupid playing in the seventh.” The Washington Evening Star called the Cleveland team the Wanderers.) That didn’t just finish the season, it finished the Spiders; they were contracted out of existence. But they have persisted in baseball history.

Two seasons before: 69-62, 81-68

Two seasons after: None

Next winning season: None

Best players: Ossie Schrecongost, 24, catcher, and Charlie Zimmer, 38, catcher, 0.9 bWAR

Best player (career): Lave Cross, 33, third baseman, 46.5 bWAR (traded to St. Louis after 38 games)

Phil Coffin is the newest member of IBWAA. A longtime editor at The New York Times, he is the author of When Baseball Was Still Topps: Portraits of the Game in 1959, Card by Card and A Baseball Book of Days: Thirty-One Moments That Transformed the Game, due out later this year. This timely and well-researched historical piece is used this week in place of the usual Dan Schlossberg column.

Timeless Trivia: Ohtani’s 50th HR Ball Could Fetch Millions in Goldin’s Auction

The minute Shohei Ohtani hit his 50th home run—his second of the night—in the top of the seventh inning against the Miami Marlins last week, the ball became a treasured piece of memorabilia. Now it is up for auction by Goldin’s, which expects to realize seven figures in the sale, which started yesterday . . .

Ohtani’s 50th home run baseball came to Goldin directly from the fan who caught it . . .

The Dodgers DH finished the game 6-for-6 with three homers, two doubles, and 10 RBI, good for 17 total bases and one of the greatest games in MLB history . . .

He also stole two bases to become the first member of the 50/50 Club . . .

The Dodgers won the game by a score of 20-4 . . .

Opening bid for the auction is $500,000, but potential buyers will have a chance to purchase it outright for $4.5 million exclusively from Sept. 27-Oct. 9 . . .

If bidding reaches $3 million before Oct. 9 however, the option to purchase privately will no longer be available and interested parties must compete and bid for the ball in extended bidding that starts at 10 p.m. EDT on Wednesday, Oct. 16.

Extra Innings

Goodbye, Oakland Coliseum. The Athletics played their last game there Thursday and became the biggest lame duck in baseball history as their Las Vegas home won’t be ready until 2028.

The team played 4,493 regular-season games there in 56 seasons, winning 2,491, and took four World Series titles and six pennants while retiring the uniform numbers of Reggie Jackson (9), Ricky Henderson (24), Jim (Catfish) Hunter (27), Rollie Fingers (34), Dave Stewart (34) and Dennis Eckersley (43).

Know Your Editors

HERE’S THE PITCH is published daily except Sundays and holidays. Benjamin Chase [gopherben@gmail.com] handles Monday and Tuesday editions, Elizabeth Muratore [nymfan97@gmail.com] does Wednesday and Thursday, and Dan Schlossberg [ballauthor@gmail.com] edits the weekend editions on Friday and Saturday. Readers are encouraged to contribute comments, articles, and letters to the editor. HTP reserves the right to edit for brevity, clarity, and good taste.