In the 1970s, Former FBI Agent Had a Central Role in Policing Pro Sports

ALSO: OAKLAND B'S SEEK TO SUPPLANT OAKLAND A'S, STARTING TUESDAY

Pregame Pepper

Which was more unlikely: Cleveland winning nine in a row or Colorado ending the streak? . . .

Struggling Mets shortstop Francisco Lindor has switched from contacts to prescription glasses in the belief that seeing better will help his offense . . .

Dodgers teammates Shohei Ohtani and Mookie Betts are both bidding for their first batting title but San Diego’s Luis (Line-Drive) Arraez is seeking his third in a row . . .

Despite the thundering hooves of Yankees sluggers Aaron Judge and Giancarlo Stanton, Houston’s Kyle Tucker leads the majors in home runs . . .

Don’t look now but Padres closer Roberto Suarez — who took the job of departed free agent Josh Hader — has emerged as a strong contender for the National League’s Cy Young Award . . .

Milwaukee catcher William Contreras, supplying speed plus power as an unlikely leadoff man, is suddenly a candidate for National League MVP — especially if Ohtani and Betts split the vote.

Leading Off

Baseball’s First G-Man, Part Two

By Paul Jackson

Henry Fitzgibbon, the first Director of Security for Baseball, excelled at avoiding publicity, despite the tabloid-friendly substance of his work. Jerome Holtzman, one of the deans of sports writing in Fitzgibbon’s time, said of him in 1972: “He’s a wonderful private eye, just shuffles around, always watching and saying nothing, though if you’ve known him for two or three years, he might give you a ‘hello.’”

A rare Fitzgibbon profile appeared in the Los Angeles Times in 1971, describing him as a “tall gentleman with thinning gray hair, with more the bearing of a bank president.” The interview Fitzgibbon gave for this piece was by far the most we could find him talking about his own work, and to hear him tell it, risk management was the name of the game.

“If we never have a case, we’ll be highly successful. Our success is not measured by what we develop to report. It’s measured by what doesn’t happen.”

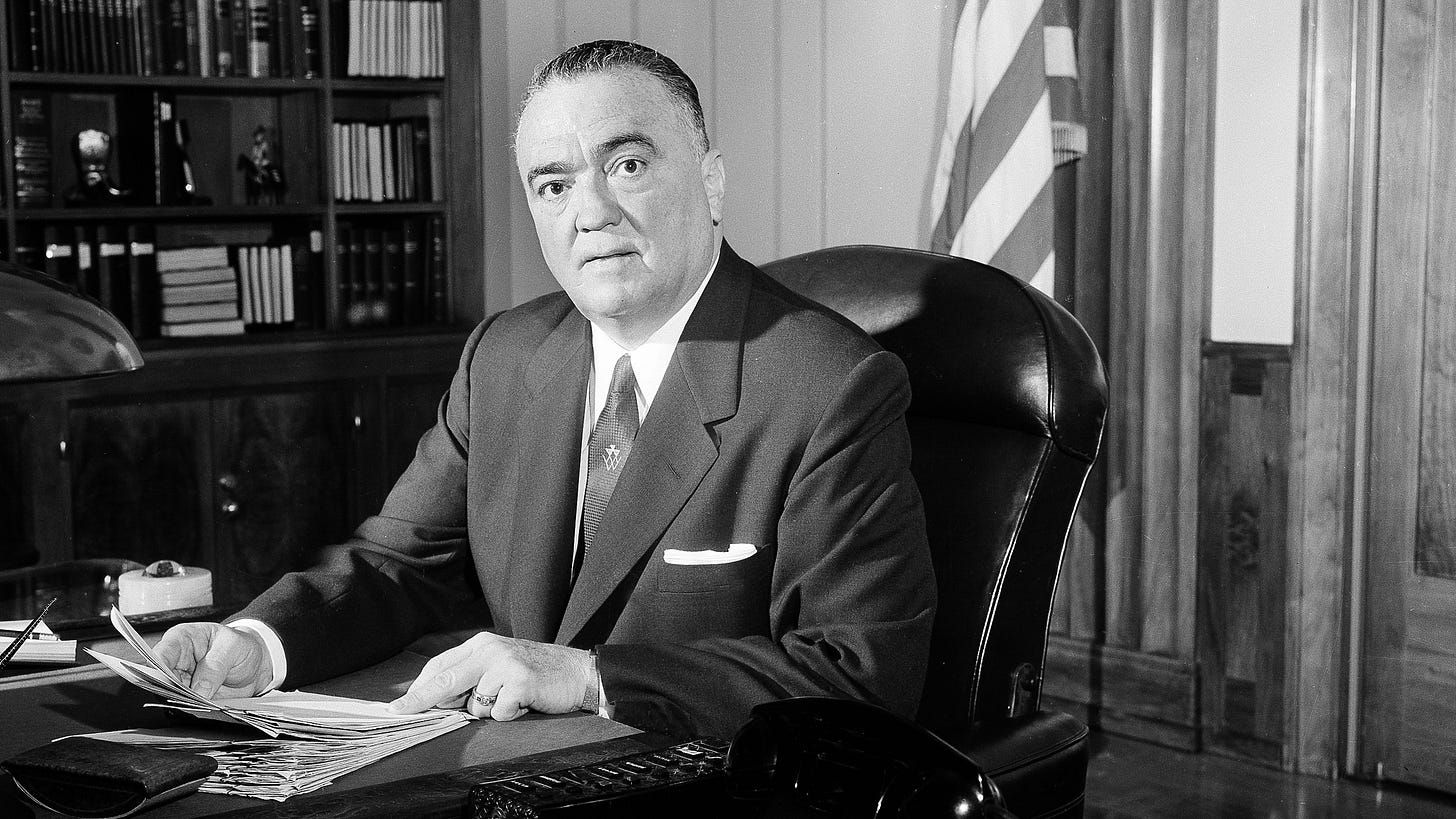

Like J. Edgar Hoover, Fitzgibbon saw gambling as the greatest danger to his new territory. “Billions are bet illegally every year on sports events–baseball, football, you name it.”

“Gamblers look for what they call an edge,” he explained. And a great way to find an edge was to build a personal relationship with a player.

As a result, he said his office’s first priority was education. “If we can inform the players and others what dangers exist in the fields of organized crime and gambling, we hope they’ll have the interest and intelligence to avoid such association.”

Though mild-mannered, Fitzgibbon never hid his origins or the pedigree that had earned him his role. A framed, autographed picture of his old boss, J. Edger Hoover, sat on the desk of his baseball office, and a lacquered truncheon hung on the wall.

J. Edgar Hoover had long sought to have the FBI in a close relationship with professional sports, and by the mid-1970s, the largest organizations had practically outsourced security matters to an unofficial wing of the Bureau.

In 1973, “Security Directors” right out of Quantico central casting were in place in the NFL, MLB, the NHL, and the NBA, bringing remarkable uniformity and consistency to an evolving profession. Three of the four directors lived in the same town, New City, New York (during their earlier overlapping time at the Bureau, they car-pooled), and they were so alike that even their childbearing habits were notably similar: three out of the four had at least four children. Fitzgibbon was the outlier in only this regard, but his deputy, Gallant, made up baseball’s deficit by having nine.

In provincial baseball, Fitzgibbon kept most of his work in-house, but the NFL security director, Jack Danahy, took the next step, building a national network of retired FBI agents, and some retired police, keeping them on retainer and ready to spring into action. This system quickly became the gold-standard, working so well that the NBA and NHL began tapping into the same freelance pool.

The men at the top all framed their roles using almost identical language: “My objective is to maintain the integrity of the sport.” This took their mission from legality up and out to morality, and everyone appreciated such a broad purview.

“These are not great civil libertarians we are talking about,” said Dick Moss, counsel for the MLB Players Association in 1976. “They are not overly concerned with players’ rights.”

“There’s too much invasion of the privacy of the player,” Arthur Goldberg, a former Supreme Court Justice complained. “This security business is just another example of the invasion.”

The Security Directors also adopted the Bureau’s emphasis on secrecy. Asked to explain how he kept tabs on baseball’s several-dozen clubs, the inscrutable Fitzgibbon had a ready response: “Security is a peculiar operation,” he said. “We don’t like to tell people how we operate.” You can see why he didn’t get many interviews.

A 1981 nationwide review of money in sports, released a few months after Fitzgibbon retired (for real), showed gambling’s soaring popularity during the prior decade, including an explosion of illegal gambling on professional sports. The money involved in illegal gambling had–at least–tripled in ten years, coinciding with a steady erosion of law enforcement resources which “decriminalized gambling by default,” the report said.

To whatever extent professional sports embraced hiring federal agents as a way to wage war on illegal gambling, given the scale of the problem, the former G-men on the payroll were just a bucket underneath an overtopping dam.

“There sure as hell is going to be another gambling scandal, just as sure as there’s going to be another earthquake in San Francisco,” a worried university president said in 1981. “It’s long overdue.”

And it was coming, no matter who was watching.

Paul Jackson writes about sports, history, and culture on Substack at Project 3.18. He has previously written for ESPN.com. Paul can be reached via email at pjacks2@gmail.com.

Cleaning Up

By Dan Schlossberg

As Archie Bunker might say, “Whoop-tee-do!”

The historic home opener of the Oakland Ballers Tuesday is sold out. Not bad for a minor-league team in a minor-league ballpark playing in a city where the major-league franchise averages under 7,000 fans per game.

The new Pioneer League team will play in a 4,000-seat ballpark far better suited to host fans than the decrepit Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum, home of the lame-duck Oakland (soon to be Las Vegas) Athletics.

According to the Ballers, the team has invested $1.6 million to bring the play area up to league standards and reactivate a historic ballpark once hailed for producing more baseball stars than any park in the country.

Infrastructure upgrades include new dugouts, a batter’s eye, netting, fencing, and a backstop. The 4,000 seats offer a comfortable viewing experience with convenient access to restrooms, food, and beverages.

More seats may become available depending upon decisions by holders of season tickets.

According to Ballers co-founder Paul Freedman, "Today marks an incredible milestone for the Oakland Ballers and all Oakland sports fans as we announce that our inaugural home opener at Raimondi Park on June 4th is sold out.

“The overwhelming demand for tickets reflects the excitement surrounding our team and its debut at Raimondi Park. As we put the final touches on our beloved Raimondi Park, we're not just preparing for a game—we're embracing a legacy.

“Raimondi Park has a storied history of producing baseball stars, and we're honored to revive that tradition in the heart of Oakland. We invite fans to join us not just for our sold-out opener, but for all of our opening week games so we can continue to show the world how we do it in Oakland.”

On game days, the Ballers will serve a variety of standard baseball fare, including hot dogs, nachos, burgers, fries, and vegetarian options, alongside beverages. Child-friendly menu options will be available, and popular food trucks will be on site on a rotating basis.

Families and children can enjoy the repaired playground area adjacent to the ballpark, providing a perfect retreat during Ballers' games and beyond. Additionally, the City of Oakland has ensured that all surrounding streets and sidewalks are undergoing or have undergone repaving ahead of the Opening Day, enhancing accessibility and safety for the neighborhood.

The Ballers are committed to ensuring fans are not reliant on personal vehicles to get to games.

A shuttle service from West Oakland BART to the field will operate continuously starting an hour before game time until half an hour after the game concludes.

In addition, a complimentary bike-and-scooter valet service will be stationed near Raimondi Park, with local bike groups facilitating cyclists' journeys to and from the park. On-site parking will be available, with three attended lots offering more than1,000 spaces, supplemented by a ride-share pickup lot and overflow options for peak volume days.

To ensure the safety and enjoyment of all attendees, security personnel will be stationed around the park area, managing crowd control and providing assistance as needed.

The Ballers are part of the Pioneer League, founded in 1939, as its first West Coast franchise. Backed by almost 50 Bay Area sports fans who believe that the true value of a sports team is its power to bring people together.

The Oakland Ballers — called B’s for short — are dedicated to delivering a joyful, community focused experience for Oakland and the entire East Bay.

According to a team spokesman, “We vow to never leave town. Built by Oakland, for Oakland, and forever Oakland.

Additional information can be found at www.oaklandballers.com.

Timeless Trivia: Durability Pays Dividends

A year ago, Atlanta teammates Matt Olson, Ozzie Albies, Austin Riley and Ronald Acuña, Jr. started 117 consecutive games from the start of the season — the first quartet to accomplish that feat in the major leagues since 1944 . . .

Olson, owner of the longest active streak in the majors, is still light years away from fellow first baseman Steve Garvey, who played an NL-record 1,207 consecutive games for the Dodgers and Padres from 1975-83 . . .

Garvey’s record is less than half of Cal Ripken Jr.’s 2,632, done entirely as an infielder with the Baltimore Orioles . . .

Ripken erased Lou Gehrig’s record of 2,130, compiled without benefit of days off for labor disputes (several, including one that lasted 232 days, occurred during Ripken’s run) . . .

Before Garvey, holders of the National League record included Billy Williams, Stan Musial, and the long-forgotten Gus Suhr . . .

AL record-holders who predated Gehrig were Everett Scott (1,307 games) and George Pinkney (577 games from 1885-90). Scott’s streak ended in 1925 . . .

Players with at least 500 consecutive games played in the 21st century: Miguel Tejada. Whit Merrifield, Prince Fielder, Alex Rodriguez, Hideki Matsui, Mark Teixeira, and Matt Olson.

Know Your Editors

HERE’S THE PITCH is published daily except Sundays and holidays. Benjamin Chase [gopherben@gmail.com] handles Monday and Tuesday editions, Elizabeth Muratore [nymfan97@gmail.com] does Wednesday and Thursday, and Dan Schlossberg [ballauthor@gmail.com] edits the weekend editions on Friday and Saturday. Readers are encouraged to contribute comments, articles, and letters to the editor. HTP reserves the right to edit for brevity, clarity, and good taste.