Passing On The Art Of Scorekeeping To Future Generations

Today, one IBWAA member discusses his lifelong love of keeping score at baseball games and how he has passed that love on to his children and grandchildren.

IBWAA members love to write about baseball. So much so, we've decided to create our own newsletter about it! Subscribe to Here's the Pitch to expand your love of baseball, discover new voices, and support independent writing. Original content six days a week, straight to your inbox and straight from the hearts of baseball fans.

Pregame Pepper

Did you know…

. . . On a recent episode of Antiques Roadshow, a scorecard from the legendary 1951 Bobby Thomson “Shot Heard ‘Round The World” game was featured as an artifact. This wasn’t just any fan-etched scorecard — it came directly from the press box. The scorecard is completely filled out, except one box is missing: Thomson’s home run, the last at-bat of the game. The owner of the artifact, whose father was in the press box that day, explained that “bedlam broke out” when Thomson hit the home run, and everyone in the press box went so berserk that they didn’t finish scoring the game. The scorecard was valued at $20,000-$25,000.

. . . Purists may scoff at the notion of keeping score digitally, but for more tech-savvy baseball fans, there are now several apps they can choose from to score any game of their choosing, including Gamechanger and iScore.

Leading Off

Keeping Score

By Russ Walsh

“Scorecard lineup here!”

Whenever I entered the ballpark in my hometown of Philadelphia, whether it was Connie Mack Stadium, Veterans Stadium, or Citizens Bank Park, those were always the first words I would hear: “Scorecard lineup here!” Our first stop after walking through the gates was always at the kiosk that was selling the day’s program with that scorecard inside and the little Phillies red pencil that came with it.

Keeping the score of the game is a family tradition passed down from my father to me, from me to my daughter, and now from me to my grandson. It is part of the grand tradition of baseball, a sport obsessed with records and statistics, to sit and watch a game while recording every pitch, every play, every nuance that can fit in a box about half a square inch.

I learned to keep score at about the same time I started playing Little League baseball in 1955. I was eight. I don’t remember my father teaching me, but I know he did. The idea appealed to me. At my Little League games, I watched over the shoulder of whatever adult, usually an assistant coach or a mom who had volunteered, was keeping score. It was important, too. Sometimes if there was a dispute on the field about how many outs there were, who was up next, or how many runs scored in the third inning, the scorebook was the final arbiter. I got good at keeping score -- sometimes when I attended games when my team was not playing, coaches would ask me to be the scorekeeper.

I honed my skill by scoring Phillies games I listened to on my transistor radio while lying in bed at night. I would get an old scorebook that had been used in a previous year (my dad was a coach) and turn to the back where there were always unused pages. Or I would improvise with some graph paper from my math homework. I can remember filling in names like Haddix, Hamner, Ennis, and Ashburn on my scorecards.

For whatever reason, one particular game I remember scoring was pitched by a Phillies player named Herman Wehmeier. I think the name intrigued me. Wehmeier pitched for several teams in the 1940s and ‘50s, with varying success, but I remember keeping score for a game he pitched against the Pittsburgh Pirates, when he went ten innings and helped win the game with a base hit in the final frame. That game is stuck in my head some 65 years later. Writing things down preserves them in the memory.

I taught my daughter Beth to keep score almost as soon as she could hold a pencil. Being my daughter, Beth had learned the game by osmosis, and she also played second base on our local softball team. Beth’s ability to keep score came in handy when I was coaching the Bristol High School baseball team in Bristol, Pa., in the late 1970s. None of my bench players wanted to keep score because, I suppose, it might have made their bench status more permanent in their minds, so I asked Beth to do it. She was very good at scoring, and it was amusing to see an eight-year-old sitting on the bench with a bunch of huge high school ballplayers hovering around her as she called out who was scheduled to bat that inning.

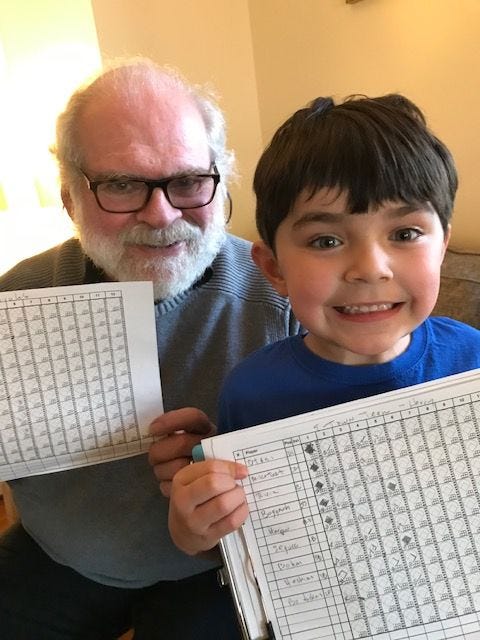

I carried all this history with me as I went to visit my grandson Henry in Elizabethtown, Pa., last week. Henry, who is approaching six years old, is a baseball fanatic. He loves the game and already has a season of T-Ball under his belt, a huge collection of baseball cards in his room, and a father and mother who love the game, too. I decided that on this visit, I would teach Henry to keep score. Since Major League Baseball was still in a lockout, I decided the best way to teach him was through a board game we had played before, Across the Board Baseball. I packed up the game and some scoresheets I printed off the internet and headed out.

We played for hours. Henry was very attentive. He quickly learned the numbers of each position and how to score a groundout to shortstop as 6-3 and a fly ball to left field as F-7. He giggled when his team scored a run and he got to fill in the diamond on the scorecard with his pencil.

When a roll of the dice showed a player had struck out, I showed Henry how to mark a K on the scoresheet.

“Why a K?” asked Henry.

I didn’t know, so we looked it up. An ESPN article called The Art of Scoring, by Jim Caple, helped me out. It seems Henry Chadwick invented and set up many of the rules of scoring a baseball game back in the 1860s. While the system has evolved over time, one thing that has not changed is the “K” for strikeout. Chadwick used the last letter of an out -- in this case the word “struck” -- as a way to identify the play. When we mark a “K” in our scorebooks today, we are carrying on a tradition that dates back to the earliest days of professional baseball.

And this is why I wanted Henry to learn to keep score and why I encourage everyone to teach their children to keep score. It is a great tradition that helps to perpetuate the great traditions of a very traditional game. No matter what changes may come to baseball, and the new collective bargaining agreement will bring several, keeping score remains a constant that allows us to replay the games in our mind’s eye.

My niece Olivia is a dedicated scorekeeper. She was taught to keep score when she was quite young by her dad, Leonard Alborn. She always kept score when she and her dad went to games. Leonard died suddenly and tragically four years ago. These days, I take Olivia to the Phillies games. Our first stop is at the kiosk where they sell the scorecards and she buys her own scorecard and pencil. Olivia keeps score at every game she attends. We always stay until the last out, and the tradition continues.

Russ Walsh is a retired teacher, diehard Phillies fan, and student of the history of baseball with a special interest in the odd, quirky, and once in a lifetime events that happen on the baseball field. He writes for both the SABR BioProject and the SABR Games Project and maintains his own blog The Faith of a Phillies Fan. You can reach Russ on Twitter @faithofaphilli1.

Extra Innings

“With [Ichiro Suzuki], every ground ball is potentially a base hit. It was always so hard to determine: If a guy made a little bit of a high throw, would Ichiro have been safe with a good throw? Did the guy have to hurry the throw because it was Ichiro? Was he going to be safe or was he going to be out? It was always tough to say. It was always tough to be the official scorer on infield grounders.

"Almost every one was an adventure for the scorer to determine whether he was going to beat that out.”

- Eric Radovich, one of the Seattle Mariners’ longtime official scorers

Can't wait to score my first Phillies game this year!

Very nice piece, Russ.