Night Lights In Major League Baseball Started With College Football

We look back at how a college football program in Kansas paved the way for night games in the Negro Leagues, and eventually across MLB.

IBWAA members love to write about baseball. So much so, we've decided to create our own newsletter about it! Subscribe to Here's the Pitch to expand your love of baseball, discover new voices, and support independent writing. Original content six days a week, straight to your inbox and straight from the hearts of baseball fans.

Pregame Pepper

Did you know…

. . . The first night game between two Major League Baseball teams took place on May 24, 1935, between the Cincinnati Reds and Philadelphia Phillies at the Reds’ home of Crosley Field. At this time, the Reds were in the midst of a years-long funk both on the field and in terms of attendance, and the country was still going through the Great Depression, so night games were thought of as a way to generate much-needed revenue for the club.

The game was originally scheduled for May 23, but a rainout pushed it to May 24.

Before the inaugural game began, President Franklin D. Roosevelt pushed a telegraph button in the White House that sent a signal to the stadium for the lights to turn on. When they lit ablaze, the crowd roared.

The Reds won, 2-1, and hosted six more night games that season.

The next MLB team to host night games was the Brooklyn Dodgers on June 15, 1938, with the Reds as the visiting team. On that night, the Dodgers were no-hit as Reds hurler Johnny Vander Meer tossed his second consecutive no-hitter.

The first American League night game was played at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park between the Philadelphia A’s and the Cleveland Indians on May 16, 1939. The World Series did not adopt night games until 1971, and Wrigley Field — the last MLB stadium to install lights — did not host night games until 1988.

Leading Off

How Lawrence, Kansas, Gave Us Night Baseball

By Paul White

Before the college football season began in the Fall of 1929, only one college in the Midwest had installed a lighting system, allowing them to play games at night. Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, had installed lights before their 1928 season and had great results, seeing an increase in attendance as well as the school’s first conference championship.

Before the 1929 season began, another small midwestern college followed suit. Haskell Institute (now known as Haskell Indians Nations University), a school in Lawrence, Kansas, that served the Native American population, decided to install lights at their football stadium.

The athletic department was one of Haskell’s calling cards at the time. Jim Thorpe, often viewed as the country’s greatest all-around athlete at the time, had once been a student there, and the football program at the tiny school was called the “Powerhouse of the West” for their willingness to take on, and often defeat, much larger schools. In recent years they’d beaten the likes of TCU, Baylor, and Michigan State.

Though the school only played two home games that season, both at night, Haskell athletic director Frank W. McDonald was thrilled with the new lights.

“Just look at this crowd,” he said on the night Haskell opened their season by defeating Friends University, 38-7. “It’s great and our lighting system is paid for.”

Bill Hargiss, head football coach at The University of Kansas, across town from Haskell, attended the game and was impressed with what he saw.

“I’ve always been against night football, but this game has just about converted me,” he said.

He wasn’t alone.

In nearby Kansas City, J.L. “Wilkie” Wilkinson, part-owner of the famed Kansas City Monarchs, was thinking of ways his team could attract more fans. Like most Negro Leagues teams, the Monarchs spent a lot of their time touring the country playing exhibitions against local teams, semi-pro squads, and, sometimes, teams of Major League players. They brought baseball to places where it wasn’t played, certainly not at the level a top Negro Leagues team could play.

Often, the Monarchs played two or even three games in one day. The more games they played, the more money they made, which was directly tied to the number of fans they packed into the stands. But they had two factors limiting attendance. One was the normal workday hours for potential fans, which limited their ability to go watch a game. The other was an inability to play after the sun went down, during after-work hours when fans were more available.

Wilkinson had experimented with primitive lighting systems in the past, hoisting gasoline-powered torches into the sky to play nighttime softball as far back as 1904. He’d never found anything that worked quite right, though, and had always abandoned the effort. When Wilkie heard about Haskell’s new lighting system, he was intrigued.

He arranged to bring his team out to Haskell Stadium, and they spent hours practicing under the lights. They took at-bats and practiced tracking fly balls and line drives.

“We discovered it wasn’t too difficult to follow the ball,” said Tom Baird, the Monarchs’ other co-owner. “We decided then and there that the Monarchs were going to play night baseball.”

The club spent most of the winter investing in the development of their own lighting system, with the added requirement that it be portable. The Monarchs needed to bring it on the road with them, setting up shop in towns across the country, playing night baseball before anyone else. Reports indicate they invested between $22,000 and $50,000 in the system, which they towed with them in several trucks.

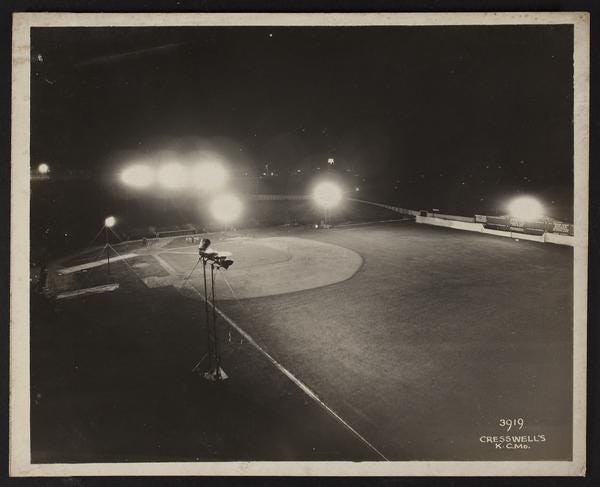

In 1930, any time the Monarchs arrived in a new town, telescoping light poles were set up around the field, powered by their own portable generators that were also towed along. The system had three 1,500-watt bulbs on each pole, and the entire system could pump out 27,000 watts of power.

It was an enormous success. In April, the Monarchs won a night game in Enid, Oklahoma. In May they won night games in Waco, Texas, and Nashville, Tennessee. In September, they crushed a team in Madison, Wisconsin, in front of “one of the biggest crowds to ever see a baseball game in this city,” but unfortunately they had to end the game early when the gas motor of their generator caught fire in the ninth inning.

A small fire or two notwithstanding, night baseball was here to stay. Within five years, the Cincinnati Reds became the first Major League team to install lights at their stadium, a move credited to Larry MacPhail having seen the lights succeed in the Minor Leagues, when the reality was that the Monarchs had been touring the country with them for years at that point. That fact was eventually recognized and is now mentioned on J.L. Wilkinson’s plaque in the Hall of Fame.

And it’s all because a small college for Native Americans in Lawrence, Kansas, saw the light first.

Paul White is an IBWAA Life Member who writes at Lost in Left Field. He is also a member of SABR and has written for their BioProject and Games Project. Paul is currently writing a book for McFarland Publishers about the history of the Hall of Fame’s recognition of the Negro Leagues. He lives with his wife in the suburbs of Kansas City.