Book Recalls the First Congressional Baseball Game

ALSO: JUSTIN VERLANDER JUST CAN'T STAY OFF INJURED LIST

IBWAA members love to write about baseball. So much so, we've decided to create our own newsletter about it! Subscribe to Here's the Pitch to expand your love of baseball, discover new voices, and support independent writing. Original content six days a week, straight to your inbox and straight from the hearts of baseball fans.

Pregame Pepper

Did you know…

Do these stats suggest Atlanta right fielder Ronald Acuña, Jr. is the top leadoff man of all time? Of all players in baseball history who have 2,000 or more plate appearances from the lead-off spot, he's the only one with an on-base percentage above .380 and a slugging percentage above .530 . . .

Revived Rangers ace Jacob deGrom went 737 days between wins — two years and seven days . . .

The Mets have won just two NL East titles (2015, 2006) since 1988, meaning no one on the current roster has ever won the division while playing for the team (Brandon Nimmo, who came up in 2016) is the longest-tenured current Met . . .

By contrast, the arch-rival Braves have taken 23 division crowns, a major-league record, plus 18 pennants, and four world championships . . .

Jasson Dominguez, emerging as the latest Yankees star, was the seventh different player in as many years to start the team’s opener in left field . . .

Yankees with Dartmouth pedigrees include bench coach Brad Ausmus, DH Ben Rice, former pitcher Jim Bettie, and one-time star third baseman Red Rolfe, for whom the Ivy League school in Hanover, NH named its baseball field . . .

The .627 winning percentage of Dodgers manager Dave Roberts entering this season was the best of the 144 men who managed at least 1,000 games. In nine years, he has nine playoff appearances, eight NL West titles, four pennants, two world championships, and the three best seasons in team history . . .

And finally, the father of Yankees pitcher Clarke Schmidt piloted the team's charter plane to Los Angeles for the 2024 World Series. A retired Marine Corps colonel and Delta Air Lines captain, Dwight Schmidt was at the controls for the team's flight to Burbank and has also piloted team charters for other road trip

Leading Off

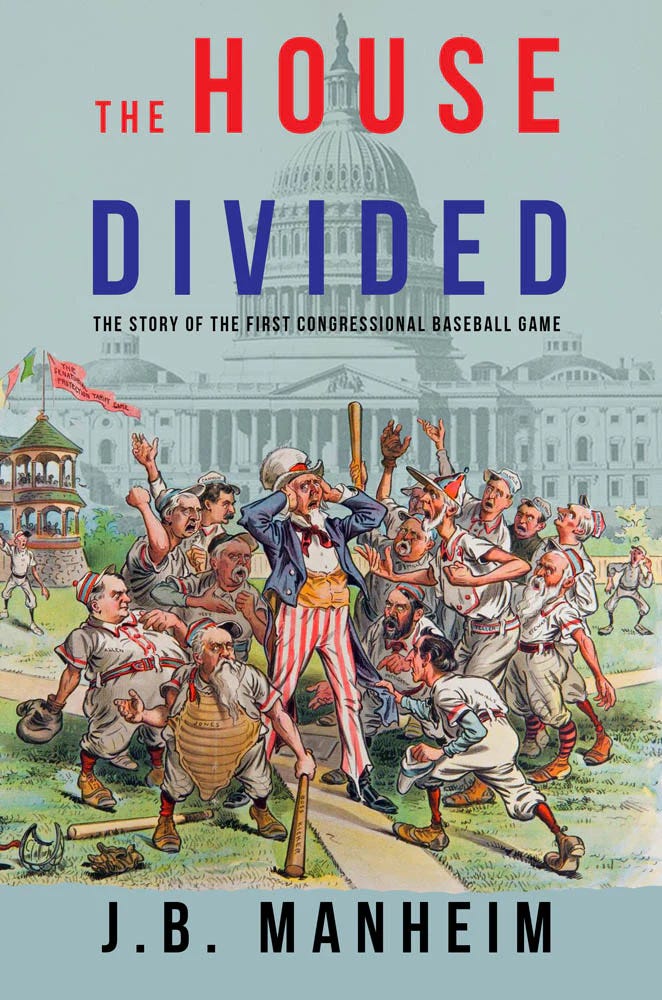

Book Review: The House Divided by J.B. Manheim

By Bill Pruden

J.D. Manheim’s The House Divided: The Story of the First Congressional Baseball Game is a highly readable and interesting though scattered work — one that offers readers both more and less than they would expect from either the title or the colorful cover.

While undeniably well-researched and full of information, the book often feels more like a collection of historical essays, each with their own focus, than a seamlessly- connected narrative.

Typical is the treatment Manheim gives to the early days of baseball in Washington.

It is a topic presented in detail and depth and one he complements with an equally fascinating look at the array of venues that hosted Washington’s teams in the years since the game’s beginning and up to the inaugural Congressional game.

We are also given a meteorological report of the once-in-a-century storm that swept through the Capital city late on the day and evening of that game.

And we are also treated to a extended report of road trip to a Baltimore baseball game by a combination of Congressmen and lobbyists, all of whom are more interested in the upcoming battle over tariff reform in the special session of Congress called by newly-inaugurated President William Howard Taft, than in anything related to baseball.

While the trip’s inclusion seems to be intended as the jumping-off point for the wandering, overly long, and ultimately unsatisfying discussion of who should be credited with making the game a reality, its greatest impact is in the informative treatment it offers about the hazards of car travel and the need for better roads in the early days of the automobile.

What we don’t get is much about the game.

Far more attention is paid to who should be credited as the founding father of this now iconic event, a title that Manheim ultimately bestows on freshman Congressman and future Pennsylvania governor John Tener, a former professional baseball player and one of the Baltimore road-trippers.

However, Tener is not given credit until Manheim has offered and then dismissed a wide range of other plausible options, ultimately returning to the previously- dismissed Tener. It is never clear exactly how he got there and that lack of clarity –- there and in other places — is the book’s greatest source of frustration.

Despite all that, I enjoyed the book and learned a lot. And yet as someone who has both worked as a Congressional aide and studied and taught politics and American history for decades, I was looking for a more cohesive and more tightly-presented narrative.

In its bits and pieces, it is fascinating and informative, but it offers a long and winding road — one no smoother than that taken by the Baltimore junketeers.

Indeed, it is the oftentimes tenuous connections Manheim makes between events, people, and resulting actions that are the most frustrating part of the reading experience. While the book is brimming with fun facts, the causation connections in particular are not always clear. Too often they are simply asserted, thus depriving the reader of a better understanding of the whys and wherefores.

This is particularly evident in the matter of the ratification of President Taft’s proposed 16th Amendment to the Constitution, allowing for Congressional enactment of an income tax.

Presented by the president with little fanfare in the midst of the debate over tariff reform, it seems almost an afterthought given the tariff’s status as the focus of the special session called by the President.

In fact, as presented throughout the narrative, the reader is led to believe that it is little more than a convenient distraction behind which the leadership can hide, while the central issue of tariff reform, something the leadership opposes, is debated.

That is the case because while the reformers see an income tax as the funding alternative that will allow for a lowering of tariffs, to the leadership it is a convenient ruse.

Even while Congress is voting to advance the Amendment, Congressional leaders —especially House Speaker Cannon and his allies — are confident in their belief that it will never be ratified in the states, thus leaving the nation’s financial landscape intact.

Secure in that belief, Cannon is able to humor, if not wholly support, the reformers, knowing that the status quo will be protected by the failure of the states to ratify the 16th Amendment.

Yet when ratification is achieved, and it suddenly becomes clear that with an income tax the country can afford to reduce tariffs, everything changes.

But while Manheim makes clear the surprise — indeed the amazement — with which Congressional leaders greeted the ratification that was never supposed to be, there is no explanation as to why the politically-astute Speaker and his allies so badly misread the political winds on the collateral issue at the heart of the political history element of the story.

While readers are treated to a day-by-day history of the special session, the connection between the battle over the tariff, the funding of the government that it provided (as well as its role as a protector of American trade interests), and its relationship to the game is never made clear but rather is a subject for conjecture and speculation.

At one point, the author says the game is intended to give the Democrats a chance to win after being consistently pummeled on the political battlefield, while at another point, he says the Congressional baseball game was intended to reduce partisan tensions. He likens it to a mother taking her children outside to get some fresh air in an effort to reduce the tension among the kids cooped up inside.

It is not a very convincing explanation, especially to anyone with much familiarity with politics, even acknowledging the differences between the politics of that era and today. Rather, it is one of the numerous places which, in a book that offers impressive detail on many topics, leaves the reader hungry for more in others.

In the end, The House Divided is a mixed bag. Interesting and informative, alternately detailed and superficial, it is paradoxically perhaps, at once both a fascinating and exasperating work, but one definitely worth reading.

Bill Pruden is a high school history and government teacher who has been a baseball fan for over six decades. He has been writing about the game--primarily through SABR sponsored platforms, but also in some historical works--for about a decade. His email address is: courtwatchernc@aol.com.

Cleaning Up

Verlander’s Quest For 300 Dims By The Second

By Dan Schlossberg

Unless and until the Kansas City Royals recall 45-year-old lefty Rich Hill from the minors, Justin Verlander will be the oldest man in the big leagues.

Technically, the 42-year-old pitcher is not even there.

A mere shadow of his former self, the three-time Cy Young Award winner just can’t avoid constant collisions with the dreaded injury list.

Signed to a one-year contract that guarantees him $15 million, Verlander has yet to win a game for his newest team, the San Francisco Giants.

And now that he’s sidelined into the month of June, he’s 0-for-the-first-third-of-the season. That is not how Buster Posey, the catcher-turned-executive, wanted to spend his 2025 budget.

Nor is it how the pitcher, still stuck on 262 wins, wanted to resume his self-admitted quest for 300 wins.

Nobody has joined the 300 Club since Randy Johnson did it in 2009, also as a member of the Giants. That leaves membership at 24, a ripe old number usually associated with Willie Mays, another Giant of the realm.

The only other 200-game winners active now are Max Scherzer (216) and Clayton Kershaw (212) but, like Verlander, both are constantly flirting with injury list stints.

Scherzer, now with the Toronto Blue Jays, and Kershaw, the long-time leading man of the Los Angeles Dodgers rotation, have given their teams the same number of wins as Verlander has given the Giants. Make that a big fat zero.

If there’s a silver lining in the black cloud that has hovered over Verlander for years, it’s that he’s looked better since joining the Giants than he did in his second sojourn with the Astros.

He had a 5.48 earned run average for Houston in 2024, working only 90 1/3 innings, thanks to shoulder inflammation and a serious neck problem.

Rocked in his final seven starts for the ‘stros, Verlander pitched so poorly that the team dropped him from its playoffs roster.

Now he has a pectoral nerve issue expected to keep him idle until June 3. When he returns, he’ll need to improve the 4.33 ERA he compiled over his first 10 outings in the City by the Bay.

To replace him on the active roster, the team could dip into its minor-league system, sign a discarded veteran like Lance Lynn or Kyle Gibson, or make a trade. And Jordan Hicks, just moved back to the bullpen after failing in the front lines of the rotation, could try again — if manager Bob Melvin can put up with his erratic performance.

Don’t expect Verlander to win his 10th invitation to an All-Star Game in July. In fact, it would be a major miracle if he’s able to overcome his latest injury and finish the season without going on the shelf again.

He’s so close to 300 wins, he can taste it. But he still needs 38 more — an average of 19 wins per season this year and next.

With only four months left this year and an owners lockout likely when the current Basic Agreement expires after the 2026 campaign, time is getting short.

Even the encouragement of wife Kate Upton might not help.

On the plus side, however, Verlander will be a shoo-in for Cooperstown five years after he finally hangs up his spikes. That could happen as early as 2030, assuming this is his last year.

HtP weekend editor Dan Schlossberg of Fair Lawn, NJ covers baseball for forbes.com, Memories & Dreams, USA TODAY Sports Weekly, Sports Collectors Digest, and many other outlets. His email is ballauthor@gmail.com.

Extra Innings: Beast & Least in the NL East

Now that Ronald Acuña, Jr. has returned to the Atlanta lineup, let’s assume the NL East race will be the same scramble that pre-season prognosticators predicted: Braves, Phillies, and Mets . . .

Philadelphia stretched its winning streak to seven with a rare shutout at Denver’s Coors Field over the pathetic Rockies Thursday . . .

Since the Braves switched from the NL West to the NL East after the 1993 season, they have 18 divisional titles, the Phils have seven, the Nationals four, and the Mets two . . .

The Marlins have never won a division crown but have two world championships by way of the wild-card route . . .

Oddly, the Pittsburgh Pirates own three NL East crowns — one more than the Mets — even though they haven’t been in the division since MLB switched to a three-division format after the ‘93 season . . .

It’s been nine years since the Mets were Beasts of the East, though their winter signing of Juan Soto was supposed to bring them instant success this season.

Know Your Editors

HERE’S THE PITCH is published daily except Sundays and holidays. Benjamin Chase [gopherben@gmail.com] handles the Monday issue with Dan Freedman [dfreedman@lionsgate.com] editing Tuesday and Jeff Kallman [easyace1955@outlook.com] at the helm Wednesday and Thursday. Original editor Dan Schlossberg [ballauthor@gmail.com], does the weekend editions on Friday and Saturday. Former editor Elizabeth Muratore [nymfan97@gmail.com] is now co-director [with Benjamin Chase and Jonathan Becker] of the Internet Baseball Writers Association of America, which publishes this newsletter and the annual ACTA book of the same name. Readers are encouraged to contribute comments, articles, and letters to the editor. HtP reserves the right to edit for brevity, clarity, and good taste.