Baseball's Two-Way Greats Started Early

PLUS: MILWAUKEE BRAVES WERE A STRONG BUT SHORT-LIVED DYNASTY

Pregame Pepper

Did you know…

St. Petersburg mayor Ken Welch says he “(has) no interest in working with this ownership group” after their decision to pull out of the proposed new stadium deal on Tampa Bay. So much for the Athletics being the most troubled franchise . . .

With three starters injured, Bruce Bochy will be hard-pressed to get his Texas Rangers off to a good start in the AL West — even if Jacob deGrom recaptures his Cy Young form . . .

Former strikeout king Spencer Strider, with his ailing elbow repaired by a brace procedure, fanned five Red Sox in 2-plus innings in his first exhibition start and is on track to rejoin the Atlanta rotation in mid-April . . .

Ex-Braves southpaw Sean Newcomb, now with the Red Sox, has bounced between majors and minors because he was never able to throw strikes consistently . . .

Former MVP Kirk Gibson has left the Detroit Tigers broadcast team to cope with Parkinson’s disease . . .

The late Les Keiter, who recreated Giants games on New York’s WINS after the team split for San Francisco, remains the most exciting baseball announcer I ever heard.

Leading Off

Two-Way Players Dominated 19th Century Baseball

By Chris Jensen

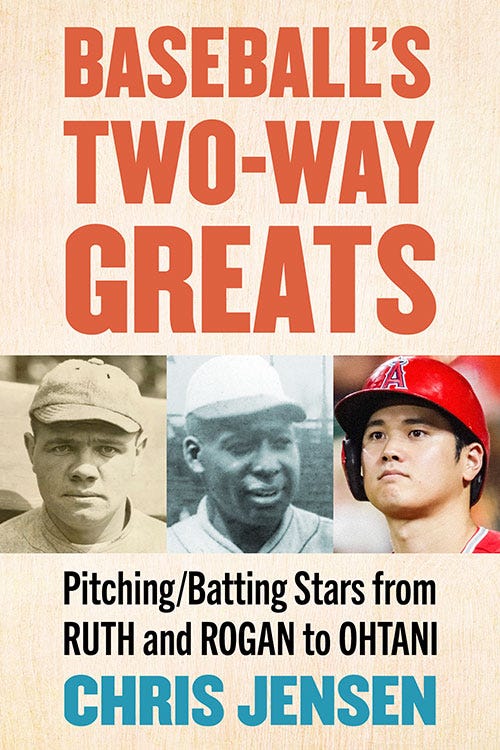

Of the 336 seasons in which a major-league player has pitched in at least 10 games and recorded more than 200 plate appearances, 291 came during the 19th century, according to research I did for my book Baseball’s Two-Way Greats: Pitching/Batting Stars from Ruth and Rogan to Ohtani.

Major League Baseball in the late 19th century was a frenetic game of shifting rules that changed on an annual basis. Starting in 1884, pitchers were allowed to throw overhand. Then in 1893, the rubber pitching slab was moved from 50 feet to 60 feet 6 inches from the rear of home plate. While pitchers could throw faster over-handed, it also meant they couldn’t keep pitching every game due to the extra strain on arms and shoulders.

Teams in the 19th century required versatile players who could play multiple positions, because rosters were nothing like the 26-man teams that compete today.

The 1876 Chicago White Stockings went through the entire season with just 11 players.

All five of the team’s pitchers also played in the field. Managers in the 19th Century did not have the luxury of a deep bench to mix and match against the competition. Teams had one or two ace pitchers who could toss 400-plus innings and mitigate the need to carry additional pitchers.

Modern player substitution was adopted in 1890 but not used frequently by managers for many years. Up until then, pitchers could only be taken out of the game due to an injury or switched out with another position, often right field.

John Montgomery Ward was baseball’s first two-way star, and he remains the only player in baseball history to record more than 2,000 hits and 150 pitching wins.

A number of additional 19th Century players stand out for their two-way accomplishments.

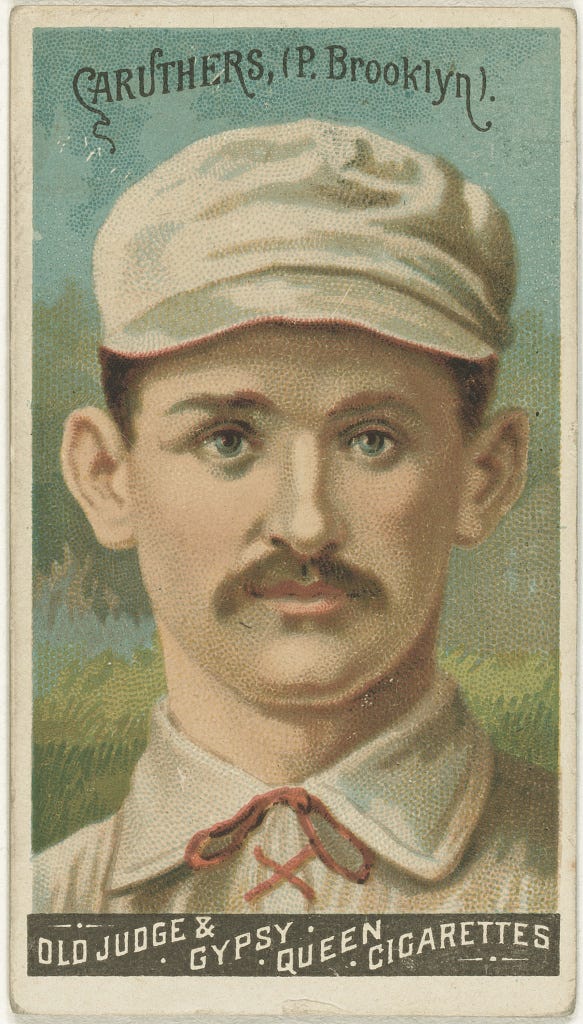

Bob Caruthers posted the two best Wins Above Replacement (WAR) totals in a season for a player who pitched at least 10 games, had 200 plate appearances and position- player WAR over 3.0. He recorded 11.5 WAR in 1886 and 10.7 WAR in 1887.

In 1886, he batted .334 (fourth in the league) and slugged .527 with 106 hits and led the American Association with .448 on-base percentage, .974 OPS, and adjusted OPS of 201. His eight homers tied for fourth in the league, and he played 43 games in the outfield and two games at second base to go with 44 pitching appearances. His 30 regular-season wins were supplemented by two more wins for the champion St. Louis Browns in the 1886 World Series.

Over 10 seasons, Caruthers generated 14.8 WAR as a position player, batting .282 with 695 hits and 152 stolen bases, getting on base at a .391 clip and recording a 134 OPS+. He posted a career record of 213-99 pitching from 1884 to 1892 with a 2.83 ERA, 298 complete games, and six straight seasons with at least 300 innings pitched.

Caruthers teamed up with another two-way star on the Browns in Dave Foutz.

Nicknamed “Scissors” due to his tall and lanky frame, Foutz collected 1,253 hits with a .276 average while playing 596 games at first base, 320 games in the outfield and pitching 251 games from 1884 to 1896. His career WAR total of 35.4 included offensive WAR of 12.4.

Foutz’s best season was 1886, when he pitched 504 innings and led the American Association with 41 wins, .719 winning percentage, and 2.11 ERA. Playing 34 games in right field and 11 games at first base that year, Foutz batted .280 and collected 116 hits, 59 RBIs, and an OPS+ of 111.

Kid Gleason only pitched during his first eight seasons, not playing much in the field those years, then had a long career as a second baseman. He had one outstanding season as a pitcher, 1890 for the Philadelphia Phillies, when he won 38 games (second in the NL) with a 2.63 ERA and finished third in complete games (54) and innings pitched (506). Gleason ended up going 138-131 over his pitching career with a 3.79 ERA. He batted over .300 three times and accumulated 329 stolen bases, 1,022 runs scored, and 1,946 hits.

Guy Hecker achieved the pitching Triple Crown in 1884 while going 52-20 with a 1.80 ERA and 385 strikeouts (seventh best all-time). He also produced a league-leading 72 complete games and 670 2/3 innings pitched, both third-best in baseball history.

The 52 wins are the third-highest figure ever.

That year, he also hit .297 with 94 hits and a 148 OPS+ for the Louisville Eclipse. His total WAR of 17.8 that season is the fifth-highest mark all-time. Two years later, Hecker led the American Association with a .341 average while winning 26 games on the mound. He remains the only pitcher to win a batting title.

On August 15, 1886, Hecker had an unbelievable day at the plate. He smacked three inside-the-park home runs to go with three singles, reaching base on an error in another at bat. His seven runs scored remains the major-league record and he pitched a complete-game four-hitter for the win.

Irish-born Tony Mullane became the first ambidextrous pitcher in major-league history on July 18, 1882. A switch-hitter at the plate but a natural righty hurler, Mullane learned to be an ambidextrous pitcher while overcoming an arm injury. He is tied with Ferguson Jenkins for 29th place all-time in pitching wins with 284.

An exceptional athlete and good fielder, Mullane stole 112 bases and had three seasons with 20 or more steals. His batting marks were inconsistent, but he was good enough to see regular action around the infield and outfield. In addition to serving as ace of the 1884 Toledo Blue Stockings, Mullane finished second on the team with a .276 average and third with 97 hits.

Other notable two-way players in the 19th century included George Bradley, Charlie Buffinton, Nixey Callahan, Win Mercer, Old Hoss Radbourn, Jack Stivetts, Adonis Terry, and Jim Whitney.

Chris Jensen has written for Seamheads, Start Spreading the News, Elysian Fields Quarterly and the Yankees Annual Yearbook. He is the author of the recently released Baseball’s Two-Way Greats: Pitching/Batting Stars from Ruth and Rogan to Ohtani as well as Baseball State by State: Major and Negro League Players, Ballparks, Museums and Historical Sites. Email him at chris.jensen81@hotmail.com.

Cleaning Up

The Team That Never Had a Losing Season

By Dan Schlossberg

Only one team in baseball history never had a losing season.

In between long residencies in Boston and Atlanta, the Milwaukee Braves lasted 13 seasons (1953-65). And they never lost more than they won.

Sure, that was the team of Warren Spahn and Eddie Mathews, imported from Boston; future home run king Hank Aaron; World Series MVP Lew Burdette; and so many others, including slugger Joe Adcock and eventual Hall of Fame second baseman Red Schoendienst. It’s also the place Joe Torre broke into the bigs as a catcher.

The Braves, whose sweep of the favored Philadelphia Athletics in the 1914 World Series made baseball history (plus the nickname “Miracle” Braves), won the 1948 National League pennant but couldn’t compete with a Boston Red Sox team powered by Ted Williams.

Braves Field was a cavernous ballpark more suitable to inside-the-park home runs in an era when fans clearly preferred the traditional long ball.

Attendance fell and the team slipped all the way to seventh (in an eight-team league) with a 64-89 record in 1952. Even though performance improved after Charlie Grimm replaced Tommy Holmes as manager, the last edition of the Boston Braves finished 32 games behind. Even the presence of Spahn (14-19, 2.98) and Mathews, who hit a team-best 25 home runs as a rookie, couldn’t save them.

But switching to Milwaukee certainly did.

Spahn (23-7, 2.10) had his best year, got great support from Burdette (15-5, 3.24) and Bob Buhl (13-8, 2.98), while Mathews (.302, 47, 135) was runner-up to Roy Campanella in the 1953 MVP voting.

The team finished 92-62, still 13 games behind the Brooklyn Dodgers but good enough for a solid second-place finish. Fans flocked through the turnstiles of the new Milwaukee County Stadium and the franchise proved one of the healthiest in either league.

A year later, a 20-year-old kid named Henry Louis Aaron made the Braves even better –- though his freshman numbers (.280, 13, 69) were certainly modest compared to what came later.

Those Braves finished third, eight games behind the New York Giants and three behind Brooklyn at 89-65.

Brooklyn rebounded to the top of the league – and won its only World Championship – in 1955 but the Braves rebounded too, finishing second at 85-69, still 13½ games from the top.

Things were closer in 1956. MUCH closer. Entering the final weekend, Milwaukee was one game ahead in the standings. They finished one game behind the powerful Dodgers with a final mark of 92-62. Fred Haney replaced Grimm early on and took the team to a .630 winning percentage (68-40) but it wasn’t enough. A.B.N.Q. = Almost But Not Quite.

Then came 1957, the best year in the history of the Milwaukee Braves. A 95-69 record was more than enough to give the club an eight-game bulge over the St. Louis Cardinals. Then they won a seven-game World Series over the Yankees, despite New York’s home-field advantage.

Aaron was National League MVP and Spahn took the Cy Young Award –- the only time either future Hall of Famer would win the coveted trophies. Acquiring Schoendienst in mid-season also helped tremendously.

A year later, Milwaukee went 92-62, giving it a comfortable eight-game edge on the Pittsburgh Pirates, but lost to the Yankees in the World Series despite winning three of the first four games.

With Schoendienst sidelined by tuberculosis in 1959, the Braves slipped to 86-68, the exact same record as the now-Los Angeles Dodgers. But they lost two straight unscheduled playoff games to the Dodgers, with Spahn and Burdette unable to increase their league-leading total of 21 wins (tied with Sam Jones of the Giants).

Second again in 1960 under new manager Chuck Dressen, the Braves posted a final mark of 88-66 – which would have been good enough to beat Brooklyn a year earlier. But Danny Murtaugh’s Pittsburgh Pirates won by seven games, setting the stage for the first World Series ended by a home run (Bill Mazeroski vs. the Yankees).

In 1961, the Braves were 83-71 but fourth, 10 games from the top, after replacement manager Birdie Tebbetts fared far more poorly than the man he replaced (Dressen).

By 1962, the romance between Wisconsin fans and their ballclub seemed to be fading as fast as the team’s fortunes. The team had a better record (86-76) but worse results (fourth place, 15½ games behind, in a league that had expanded to 10 teams).

Unhappy ownership then tapped colorful and innovative Bobby Bragan as manager. Often unspoken and unpredictable, Bragan’s Braves got a great year from the 42-year-old Spahn (23-7, 2.60, seven shutouts) but the manager left him in for a 16-inning, 1-0 loss in chilly San Francisco and the pitcher was never the same.

It was the last winning season for Spahn, who won more games than any pitcher after World War II and more games (363) than any left-hander in baseball history.

The Milwaukee Braves went on winning: 84-78 during a sixth-place season in 1963, 88-74 (fifth but only five games behind St. Louis) in 1964, and fifth again (86-76, 11 games out) in 1965, a lame-duck season in Milwaukee because ownership had already announced a move to Atlanta.

Bragan, the last manager of the Milwaukee Braves, would become the first manager of the Atlanta Braves. But he lasted only 111 games before coach Billy Hitchcock replaced him, reinstated the lefty-hitting Mathews from platoon status, and stabilized the ballclub. He also refused to use Rico Carty as a catcher — not even once.

At least Brash Bobby kept the string intact: no losing seasons for the Milwaukee Braves.

Former AP sportswriter Dan Schlossberg of Fair Lawn, NJ is the author of 42 baseball books, including Hank Aaron biographies 50 years apart. He covers the game for forbes.com, Memories & Dreams, USA TODAY Sports Weekly, Sports Collectors Digest, Here’s the Pitch, and many other outlets. Dan’s email is ballauthor@gmail.com.

Timeless Trivia

“Being out there for the first one is special. It’s like the first day of school. It’s like Christmas Day for baseball. Opening Day is always special, and I’m appreciative of the moment.”

— Atlanta Braves lefty Chris Sale, the NL’s defending Cy Young Award winner

Sale made his first Opening Day starts for the White Sox in 2013, 2014 and 2016. He also drew the honor with the Red Sox in 2018 and ’19 . . .

He made those starts during a span in which he finished in the top six in American League Cy Young Award voting over seven straight seasons (2012-18) . . .

Sale shares the record for consecutive All-Star Game starts (3) with Lefty Gomez and Robin Roberts . . .

He won the National League’s Triple Crown of pitching last year after finishing with an 18-3 record, 2.38 earned run average, and 225 strikeouts, also leading National League starters with 11.4 whiffs per nine innings . . .

His career ratio of 11.1 strikeouts per nine innings leads all active starting pitchers not named Blake Snell (11.22).

Know Your Editors

HERE’S THE PITCH is published daily except Sundays and holidays. Benjamin Chase [gopherben@gmail.com] handles the Monday issue with Dan Freedman [dfreedman@lionsgate.com] editing Tuesday and Jeff Kallman [easyace1955@outlook.com] at the helm Wednesday and Thursday. Original editor Dan Schlossberg [ballauthor@gmail.com], does the weekend editions on Friday and Saturday. Former editor Elizabeth Muratore [nymfan97@gmail.com] is now co-director [with Benjamin Chase and Jonathan Becker] of the Internet Baseball Writers Association of America, which publishes this newsletter and the annual ACTA book of the same name. Readers are encouraged to contribute comments, articles, and letters to the editor. HtP reserves the right to edit for brevity, clarity, and good taste.