A Look Inside 'Field of Schemes'

ALSO: WELCOME CHANGES TO HALL OF FAME ERAs COMMITTEE RULES

Pregame Pepper

Did you know…

Yankees ace Gerrit Cole missed two months early in 2024 but will be out for all of 2025 and half of 2026 after Tommy John surgery on his pitching elbow . . .

New York could also lose DH Gioncarlo Stanton for the season if he needs surgery on both of his ailing elbows . . .

MVP contender and defending AL batting champion Bobby Witt, Jr. (forearm contusion) avoided any fractures after being hit by a pitch in the left forearm/wrist area Wednesday. Witt is coming off one of the best seasons in franchise history. He hit .332/.389/.588 and led the majors with 211 hits, including 45 doubles and 32 home runs. He also stole 31 bases and earned Gold Glove and Silver Slugger honors . . .

Steve Cohen’s Mets have spent more in four years than Marlins, Pirates, and Rays combined over the past 21 seasons . . .

Marc Badain, just named president of the Oakland-Sacramento-Las Vegas Athletics, is the former president of the NFL’s Raiders, which also moved from Oakland to Las Vegas . . .

Now that their new stadium deal is dead in the water, here’s betting the next team to move will be the Tampa Bay Rays — though MLB does not want to lose a potential $2 billion “entry fee” if it chooses a potential expansion city (Nashville? Charlotte?).

Leading Off

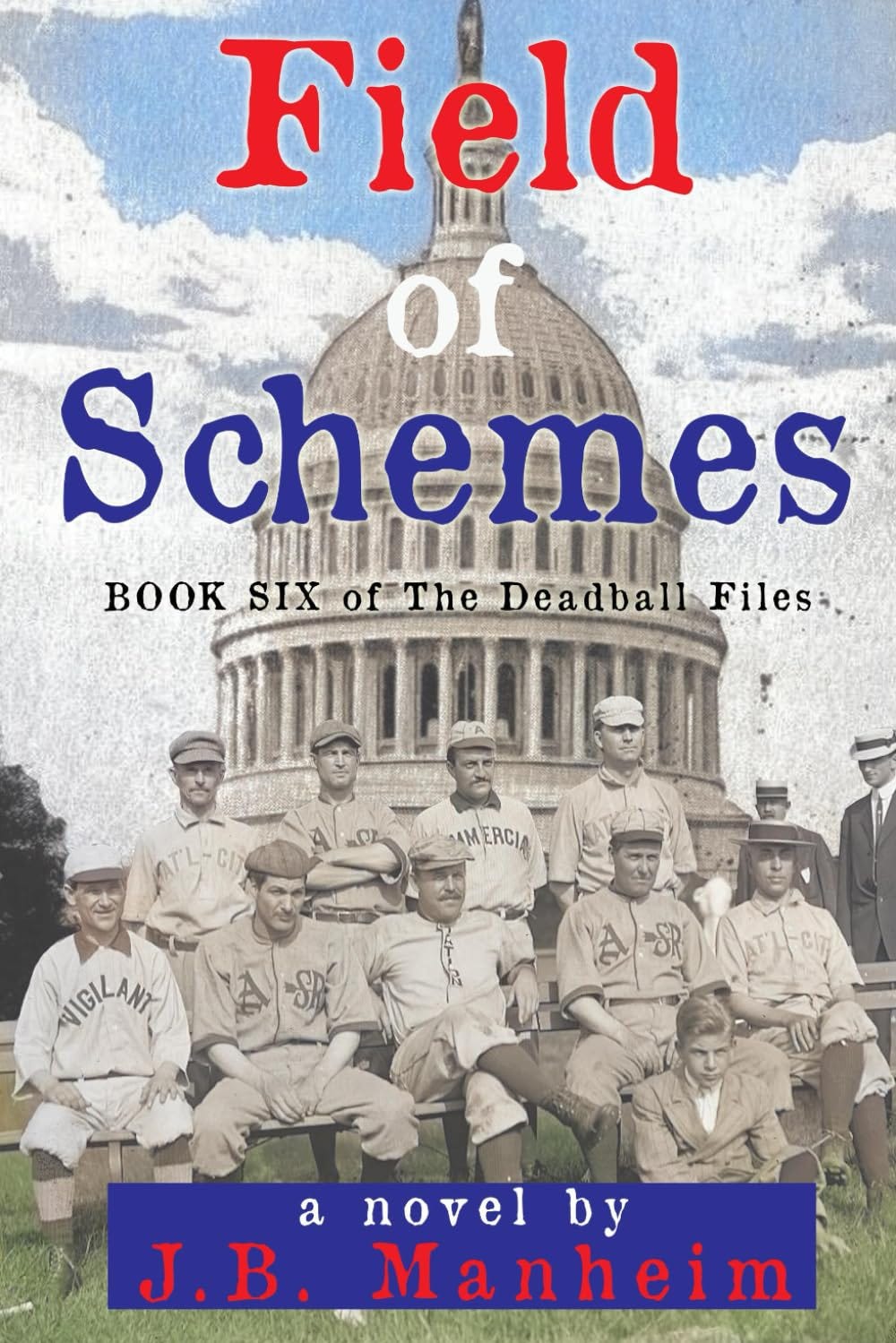

Book Review: J.B. Manheim’s ‘Field of Schemes’

By Kris Rutherford

The latest in J.B. Manheim’s series of baseball historical fiction, The Deadball Files, features Book Six, otherwise entitled Field of Schemes.

As its genre implies, Field of Schemes is part history and part fiction, with an additional dose of mystery that keeps the reader guessing throughout the work just what is and isn’t pure truth in the history and ongoing evolution of baseball.

It was published this spring by Sunbury Press.

Manheim’s grip on the internal aspects of America’s national pastime is intriguing —and makes the mixture of fact and storytelling more palpable to the reader.

Just what of baseball’s glorious and inglorious past is the result of Manheim’s research versus that of his imagination is something the reader must discern throughout each page of the 219-page work.

A mixture of personalities from history, including politicians and ballplayers, mixed with a believable group of fictional characters –- both protagonists and antagonists –- keeps the reader’s eyes on the turning pages.

The quest to determine which of Manheim’s tellings is based in fact keeps the attention of readers as they make equal attempts to discern fictional depictions used to convey a story of what could be in the annals of baseball history beginning at the turn of the 20th Century and carrying the reader right up to the present day.

In short, Manheim’s work is a tale of the history of gambling in baseball –- from the rudimentary techniques gamblers, gangsters, and blackmailers of the early days utilized (i.e., the 1919 Black Sox scandal) to what some nefarious characters with an inside knowledge of the subtleties of the game might be inclined to use to their advantage in the 21st century.

Whether fact or fiction, Manheim displays an in-depth knowledge of everything from the statistical aspects of gambling –- what is and, again, what could be –- to the manufacture of baseball equipment to put forth a telling, disturbing account of how gambling has and could impact the game.

His descriptions of aspects of gambling under baseball’s relatively new ties to online betting sites are like a trip into the underworld of a sport that, at least in its most nefarious aspects, has ties throughout the world and involves everything from the darkest corners of the internet to the choice of where and how baseballs are constructed –- and even marked –- in places like Central America and China.

Any work of fiction must have its characters, and Manheim does an excellent job of describing interactions of those made in his creation to those who have a basis in American history.

Even his depiction of the Commissioner of Baseball is convincing, despite the contriving movements of the man which the discerning reader can infer as fictional.

Still, Manheim’s descriptions of what the Commissioner of the game could become if given the inclination should be enough to pique the interests of even Rob Manfred, the controversial current and 10th Commissioner of the national game.

Manheim’s blend of those characters, true and fictional, who have a historical interest in baseball versus those like an investigative sportswriter with a notable reputation make for an intriguing tale of both the public and private face of baseball — even as deep as the underworld of which the casual fan has little, if any, awareness.

Indeed, the secrets of the game in Manheim’s work are stored in vaults to and of which only the most privileged have access and even fewer have knowledge.

Some may read J.B. Manheim’s Field of Schemes and consider it a partial indictment of baseball’s recent flirtation with online gambling sites, and they would likely be correct.

The author’s knowledge of the sport and of the many aspects that influence the outcome of a specific game, inning, out, and even a pitch are remarkable — and presented in an engrossing format using dialogue as opposed to strict narrative of facts that keep the reader guessing as to what is reality as the plot moves forward.

Likewise, the distinguishable facts that the author describes –- like the lifespan of the average baseball being 1.5 pitches -– are a gold mine of interest to even the casual fan.

A reader of Field of Schemes may take the work as a commentary on politics and the media, upon which the author is an avowed expert. There’s a backdrop of baseball as a unique presentation of how political systems and the media work together –- and at opposition –- to deliver a version of truth to the outside world.

Conversely, the reader may take the work as a baseball story instead, backed by the same politics and media savvy that often fills the pages of investigative sport journalism found on such online sites as ESPN and The Bleacher Report.

In any event, Field of Schemes is exactly what the author intends it to be and so describes in its introduction: a journey in which the reader becomes lost in the blend of fact vs. fiction, eventually emerging from the tale a little more weary of the innocent game schoolboys play and the multi-billion-dollar industry it has become both on the field and as a parlay for professional gamblers and the underworld of sport.

IBWAA member Kris Rutherford is the author of two mass-published books on the history of Texas League baseball including Baseball on the Prairie, How Seven Small-Town Teams Shaped Texas League History and The Galveston Buccaneers: Shearn Moody and the 1934 Texas League Championship. Rutherford spent the years 2013-2017 as a contributor to The Texas League Newsletter. He has also authored two works of youth sports fiction, Batting Ninth and Nothin’ But Net. His historical articles of countless Texas baseball personalities can be read on his blog “Me and Jerome,” accessible from his website www.krisrutherford.com.

Cleaning Up

Hall’s Eras Committee Rules Get Pre-Season Revision

By Dan Schlossberg

The Baseball Hall of Fame has changed its Eras Committees eligibility. Beginning with the upcoming year, any candidate on an Eras Committee ballot who does not receive at least five of 16 votes will be ineligible for consideration during their era’s next cycle. A candidate who receives four or fewer votes on two separate occasions is ruled permanently ineligible for future consideration.

That’s a giant step in the right direction but it isn’t enough.

The size of both the ballot and the voting panel need to be increased.

Until now, the ballot has been compiled by a committee that whittles its size to eight names. And the selection committee has had only 16 members.

Although there’s constant turnover in the makeup of both the ballot selection committee and the actual voting committee, it’s still too small — especially if it adheres to the traditional 75 per cent — or 12 out of 16 votes — required for election to the Hall of Fame.

To cite some examples, Class of 2025 electee Dick Allen missed earlier election by a single vote twice. So did manager Lou Piniella, who’s still on the outside looking in.

Former Dodger standouts Tommy John and Steve Garvey also would have fared better with a bigger and more versatile panel.

And it’s fair to wonder whether Marvin Miller would be enshrined today after going 0-for-7 in his earlier attempts to land a spot where none truly exists for labor leaders.

Already, the Eras Committees select candidates from early baseball in one election, before 1980 in another, and managers, executives, and owners in a third.

That’s confusing, since the original Veterans Committee considered all candidates at once — and also since any players, including new inductees Dave Parker and Allen — span multiple time-frames.

Since many voters don’t fill out their ballots completely, it’s become exceedingly hard to gather 75 per cent of the vote. That’s the only logical reason a man like Dale Murphy, with consecutive MVPs and runner-up finishes in both home runs and RBIs during a single decade, can’t make any headway.

If the annual vote did not differentiate between players, managers, owners, or peak seasons, here are the Top Ten men most deserving of election by the veterans:

Dale Murphy — consecutive MVPs, 5 Gold Gloves, 2 HR crowns, 30/30 year

Lou Whitaker — great Tigers 2B should have been elected before Trammell

Charlie Finley — innovative A’s owner and one-man front office won 3 WS

Luis Tiant — big-game pitcher who starred for several AL clubs

Tommy John — 288 wins, 12 shy of “certain” election if not for elbow surgery

Lou Piniella — Player, manager, and GM who could win in any category

Steve Garvey — Durable, dependable first baseman hit for power and average

Thurman Munson — Too bad lane crash ended career prematurely

Lew Burdette — Warren Spahn’s sidekick was 1957 World Series MVP

Cito Gaston — Who can argue with two world championships?

Honorable Mention: George Steinbrenner, Don Mattingly, Thurman Munson, Danny Murtaugh, Leo Mazzone, Scott Boras, David Wright, Alvin Dark, Joe Niekro, John Franco.

Former AP sportswriter Dan Schlossberg of Fair Lawn, NJ is currently on a book-signing tour that will take him to the Atlanta All-Star Game and the Hall of Fame, plus assorted libraries, service clubs, schools, and synagogues. Contact him via ballauthor@gmail.com.

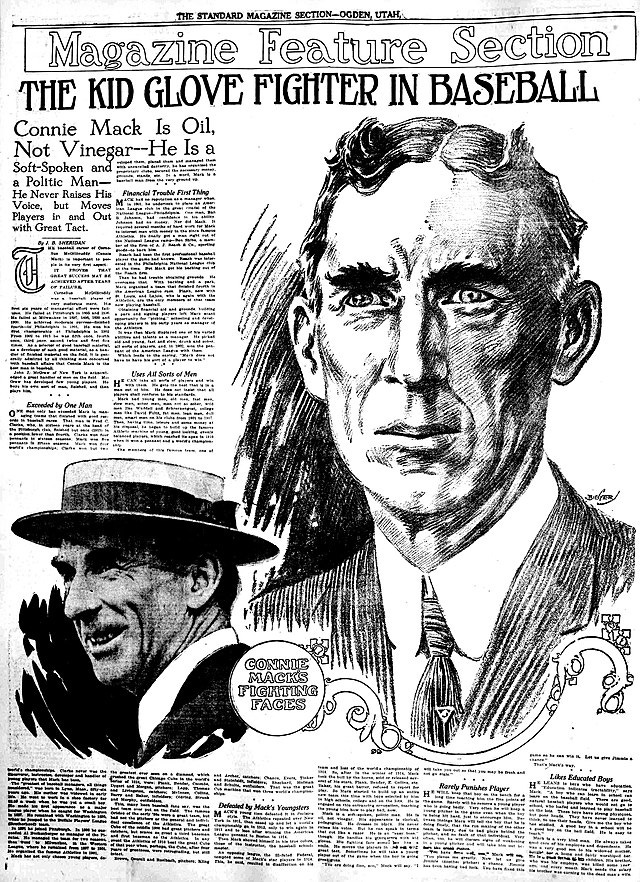

Timeless Trivia: Connie Mack’s Marks Can’t Fall

Because he was a club owner who wouldn’t fire himself, Connie Mack managed the Philadelphia Athletics from 1901-50, finishing with more wins (3,582), more losses (3,814), and more games than any other pilot.

Called ‘the Tall Tactician’ because he stood 6’2” tell and always wore a business suit that made him seem taller, Mack won nine pennants and went 8-3 in World Series play (his 1902 team was the last to win a pennant before the Series started).

He signed Rube Waddell, traded Shoeless Joe Jackson, and built three great dynasties: one early in the 20th century, one just before the advent of the Federal League, and a third as the Roaring ‘20s morphed into the Tumultuous ‘30s.

His Athletics were the first team to train in Fort Myers, a sleepy Southwest Florida backwater where he soon joined winter residents Thomas Edison and Henry Ford as local celebrities.

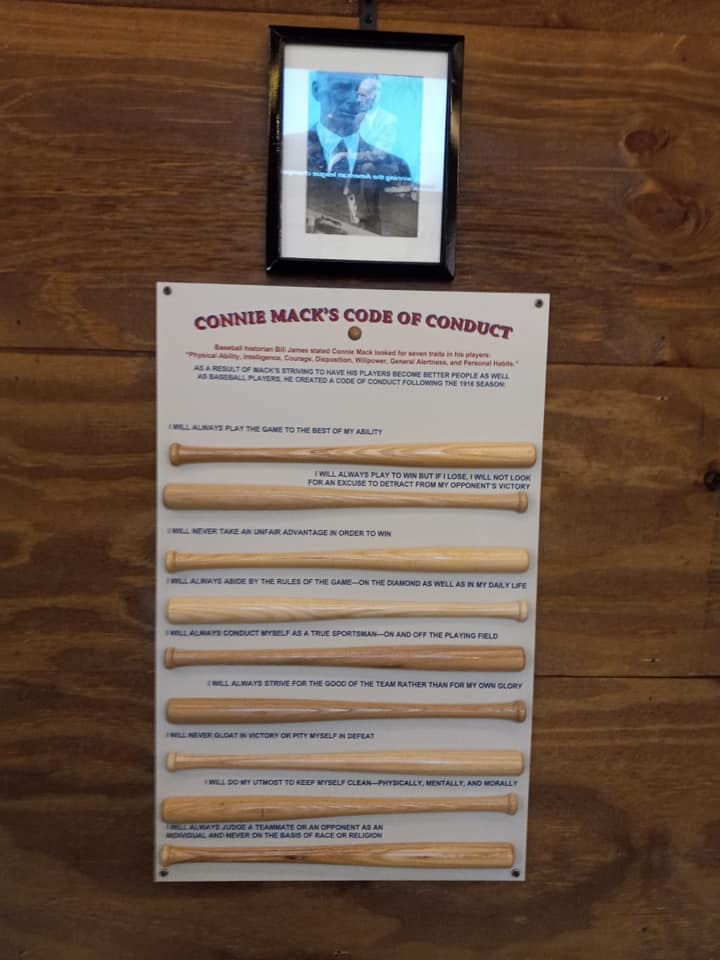

Mack eschewed uniforms and dressed instead in civvies, distinguishing himself from other managers. Because he respected intelligence, he also hired more college products than any clubs.

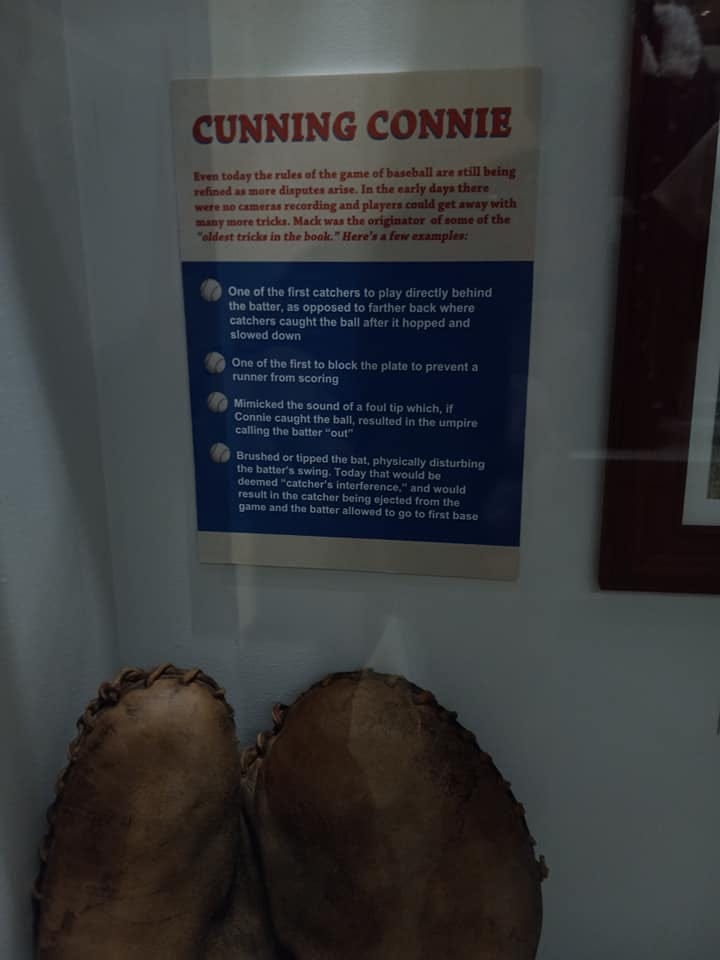

The son of Irish immigrant parents, including a Civil War vet, Mack made his debut as a player in 1886, lasting 11 seasons as a good-field, no-hit catcher before becoming a manager and part-owner. He was the first catcher to stand directly behind home plate rather than in front of the backstop.

A proper Massachusetts native, Mack never drank or swore — making himself more like star Giants pitcher Christy Mathewson than John McGraw or any of his fellow managers.

By the time he reached his 80s, however, the game had passed him by. Mack sometimes slept during games, made questionable decisions, and refused to spend money even for such basic expenses as a phone line from dugout to bullpen.

When he retired at age 89, he was succeeded by Jimmie Dykes, who later claimed fame of his own when he was traded for rival manager Joe Gordon.

A Hall of Famer since 1937, Mack died at age 93 in 1956.

Know Your Editors

HERE’S THE PITCH is published daily except Sundays and holidays. Benjamin Chase [gopherben@gmail.com] handles the Monday issue with Dan Freedman [dfreedman@lionsgate.com] editing Tuesday and Jeff Kallman [easyace1955@outlook.com] at the helm Wednesday and Thursday. Original editor Dan Schlossberg [ballauthor@gmail.com], does the weekend editions on Friday and Saturday. Former editor Elizabeth Muratore [nymfan97@gmail.com] is now co-director [with Benjamin Chase and Jonathan Becker] of the Internet Baseball Writers Association of America, which publishes this newsletter and the annual ACTA book of the same name. Readers are encouraged to contribute comments, articles, and letters to the editor. HtP reserves the right to edit for brevity, clarity, and good taste.