IBWAA members love to write about baseball. So much so, we've decided to create our own newsletter about it! Subscribe to Here's the Pitch to expand your love of baseball, discover new voices, and support independent writing. Original content six days a week, straight to your inbox and straight from the hearts of baseball fans.

Pregame Pepper

Did you know…

Lefty Carlos Rodón has not thrown a big league pitch since signing a six-year, $162 million contract with the Yankees in December. When asked if a July return could be realistic, Rodón said that he could not put a timeline on his recovery . . .

When the week began, the Braves owned a National League-best 24-11 record, matching the 1969, ‘97 and ‘98 teams for the best 35-game start in franchise history . .

Kansas City southpaw Ryan Yarbrough went on the 15-day injured list after suffering multiple head fractures when a batted ball struck him in the face . . .

Baltimore’s Kyle Gibson had induced 10 groundball double-plays by May 7 . . .

Oriole teammates Adley Rutschman and Gunnar Henderson were roommates in college . . .

Over the first month of this season, the Mets had their worst starting pitching since the hapless expansion club of 1962 . . .

The Braves are on pace to win 111 games but probably won’t. Since 1906, the lone NL team that did was the 2022 Dodgers, which lost to the Padres in the playoffs. Four teams, including the Braves, won in triple digits last season, a major-league record . . .

Atlanta’s two best starters, Bryce Elder and Spencer Strider, were selected in consecutive rounds (the fourth and fifth) of the same amateur draft.

Leading Off

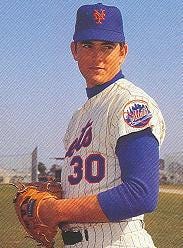

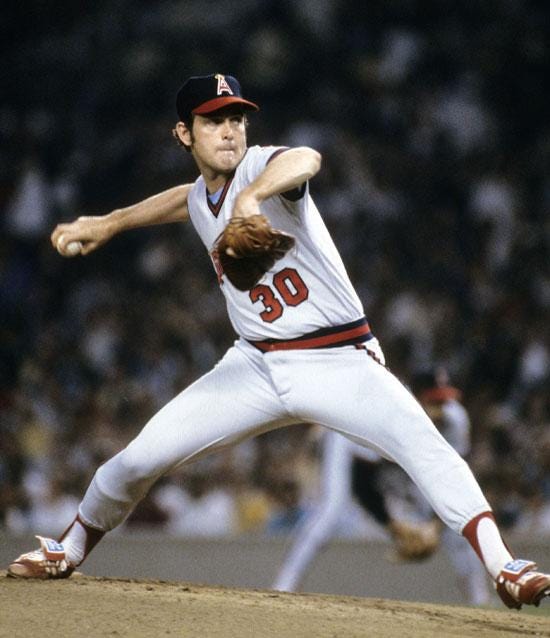

Nolan Ryan’s Final Save

By Paul White

Fifty years ago today, on May 12, 1973, Nolan Ryan recorded the third and final save of his lengthy Hall of Fame career.

When he first arrived in the big leagues with his blazing fastball in 1966, the New York Mets didn’t really know what to do with Ryan, and that never really changed. He had just a brief call-up in 1966, followed by a lost season in 1967 in which Ryan was sick, serving in the Army Reserve, or pitching just 11 innings briefly in the minor leagues.

When he returned to the Mets in 1968, Ryan mostly started, and was great at first, but then the wheels fell off in June and July and he was farmed out again. When he was recalled in September, he made just three appearances, all in relief. The next year, as the Mets and their young pitching staff finally broke through and won the World Series, Ryan was primarily a reliever for the only time in his career. The team had a collective ERA of 2.99, while Ryan’s stood a half-run higher.

The 1970 season saw similar results from him, and the same in 1971. Overall, in his time with the Mets, Ryan started 74 games and posted an ERA of 3.57. In his 31 relief appearances, he had an ERA of 3.70. It seemed that the Mets couldn’t agree on which role he should fill, so they included him in a trade to the California Angels for Jim Fregosi before the 1972 season.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

Though the Angels already had a decent group of starting pitchers in Andy Messersmith, Clyde Wright, and Rudy May, they made Ryan a full-time starter for the first time in the big leagues. He responded immediately, leading the league with 9 shutouts and 329 strikeouts, while making the All-Star team for the first time and finishing 8th in the voting for the Cy Young Award. It would seem his days as a reliver were done.

And, for the most part, they were. But a few factors combined on the night of May 12, 1973, to put Ryan on the mound for a save opportunity.

The first was the Angels awful bullpen that year. They would finish the season with just 19 saves as a team, lowest in the major leagues. It not an accident that the Angels’ rotation led the league in complete games in 1973. Their poor bullpen demanded that the starters pitch as long as possible.

The second factor was that the Angels, despite their terrible bullpen, had a decent record to that point in the season. They had entered their series against the first-place White Sox with a 13-11 record, trailing them by just 4 games. A sweep of the series would have tied them for first place.

They lost the first game, 4-3, in 12 innings when reliever Ron Perranoski, in one of the final games of his career, surrendered the winning run. Then the final factor came into play.

In the second game of the series, Nolan Ryan had one of the worst starts of his life.

The first batter he faced, Pat Kelly, hit a double to right field, and advanced to third on a fly ball by Carlos May. That was the only out Ryan would record. Dick Allen scored Kelly with a double. After a walk and a single loaded the bases, Allen stole home for the second run. A wild pitch moved up the other runners before another double scored them. Ryan was pulled at that point, but the runner he left on base later scored. The final damage was five earned runs on four hits and a walk, a pair of wild pitches, and no strikeouts in just one-third of an inning. The Angels lost the game and stood six games out.

So, when Angels manager Bobby Winkles found his team leading the third game of the series, 6-5, in the 8th inning, and reliever Dave Sells put the first two White Sox hitters on base with singles, he didn’t hesitate to bring in Ryan for his first relief appearance as an Angel. There was no one better in the bullpen, and Ryan was fresh from his abbreviated start the night before.

Ryan was at his dazzling best. A tapper back to the mound resulted in a force out at third base, then Ryan struck out Johnny Jeter, walked Pat Kelly (because no Nolan Ryan appearance was complete without a walk), then caught Allen looking for the third out. The ninth inning was even quicker. Ryan struck out the first two batters before retiring Rick Reichardt on a fly ball to end the game and secure the final save of his career.

That was not Ryan’s final relief appearance, but he probably wishes it was. In August he was brought into a game in Yankee Stadium and was roughed up, surrendering two runs on three hits and a walk in just a third of an inning. And the next season he relieved Frank Tanana in a game against the Twins and promptly blew the save by giving up home runs to fellow Hall of Famers Harmon Killebrew and Rod Carew. It was a sad ending to Ryan’s career as a reliever.

Just three days after his final career save, Ryan threw the first of seven no-hitters in his career. It safe to say that no one remembers his brief time as a reliever given how well his career as a starter worked out.

Paul White is an IBWAA Life Member who writes at Lost in Left Field. He is also a member of SABR and has written for their BioProject and Games Project. Paul is currently writing a book for McFarland Publishers about the evolution of the Hall of Fame’s recognition of baseball’s racial and ethnic pioneers. He lives with his wife in the suburbs of Kansas City.

Cleaning Up

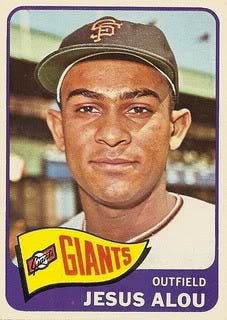

Four Alous Carved a Niche In Baseball History

By Dan Schlossberg

The San Francisco Giants have had a rich and colorful history since coming to the Pacific Coast in 1958.

After importing Willie Mays from New York, they added four more future Hall of Famers in Orlando Cepeda, Willie McCovey, Gaylord Perry, and Juan Marichal.

They made wind and fog major factors in game outcomes, with little Stu Miller forced into an All-Star Game balk by the elements.

And they brought three brothers into the big leagues in time for their careers to overlap.

In fact, on Sept. 10, 1963, Felipe, Matty, and Jesus Alou made history not only by batting in the same inning but by producing identical results: groundouts against the not-so-illustrious Carl Willey of the New York Mets. It was the only time three brothers hit in the same half-inning.

They made more history five days later by appearing in the same outfield, with Matty, Felipe, and Jesus from left to right for the last two innings of a Giants-Pirates game. They would repeat that performance once more before Felipe was traded to the Braves.

Together, the three Alous combined for 5,000 hits in 47 seasons, most of them with the Giants.

With 5,094 hits, they had more hits than the DiMaggios, Delahantys, Sewells, Boyers, Aarons, or any other brother combines.

They could certainly hit: Matty won the NL batting crown with a .342 mark for the 1966 Pirates, while Felipe finished second with a .327 average in Atlanta. It was the only time brothers finished first and second in a major-league batting derby.

All four Alous who played in the majors (including Moises, son of Felipe) appeared in the World Series and produced three home runs — all by Moises with the 1997 Marlins. Moises also had his family’s best batting average (.321) in the Fall Classic.

Felipe, the second Dominican big-leaguer after Ozzie Virgil, became the first Dominican to reach 2,000 hits and 200 home runs (Sammy Sosa soon joined him).

He later managed the Montreal Expos, where he became the fifth man in major-league history to have his son as one of his players. The others were Connie Mack, Yogi Berra, Cal Ripken, Sr. (twice), and Hal McRae, with Bob Boone joining them later.

Moises turned out to be the family standard-bearer as a player, hitting .303 with 332 home runs and making the National League All-Star team six times.

Former AP sportswriter Dan Schlossberg of Fair Lawn, NJ is writing a Hank Aaron book and promoting another title, Baseball’s Memorable Misses: an Unabashed Look at the Game’s Craziest Zeroes. He’s booking appearances by email: ballauthor@gmail.com.

Timeless Trivia

“Obviously the Cardinals were used to one guy behind the plate for close to two decades. The nuances of that position, maybe very subtle, are what a lot of our pitchers were used to. What we were seeing was a lack of confidence. Normally, you would say, why didn’t you address this in spring training? But in spring training, it’s so different in terms of what people are trying to work on. Pitchers are going a couple of innings. It doesn’t really count.”

— Cardinals GM John Mozeliak on turning catcher Willson Contreras into a DH

Vida Blue, who passed earlier this week, was the last switch-hitter to win the American League MVP award and one of only two to ever win it, following Mickey Mantle. The DH was two years from being introduced to the American League during that 1971 season, and since Blue hit from both sides of the plate he was and is the last switcher to win the award in the AL.

Carl Erskine not only threw the first pitch at the L.A. Memorial Coliseum but was the first Dodger in the Modern Era to throw two no-hitters in his career . . .

Warren Spahn threw more gopher balls (18) to Willie Mays than any other pitcher . . .

Since World War II, the man with the most seasons of at least 10.0 WAR is Willie Mays with six: 1954 (10.4), 1958* (10.2), 1962 (10.5), 1963 (10.6), 1964 (11.0) & 1965 (11.2). The only other hitters with more than two are Mickey Mantle and Barry Bonds with 3 each. Carl Yastrzemski, Cal Ripken, Jr. and Mike Trout have two apiece ..

Mays, at 92 the oldest living Hall of Famer, had 23 hits in his 24 All-Star games. His 20 runs and 40 total bases (tied with Musial) are also ASG records. Ted Williams once accurately observed, “They invented the All-Star game for Willie Mays!”

Know Your Editors

HERE’S THE PITCH is published daily except Sundays and holidays. Benjamin Chase [gopherben@gmail.com] handles Monday and Tuesday editions, Elizabeth Muratore [nymfan97@gmail.com] does Wednesday and Thursday, and Dan Schlossberg [ballauthor@gmail.com] edits the weekend editions on Friday and Saturday. Readers are encouraged to contribute comments, articles, and letters to the editor. HTP reserves the right to edit for brevity, clarity, and good taste.

I believe Nolan Ryan could make a roster still today 😀