Willie or Not? Was Mays Greatest Player Of All Time?

ALSO: OVER-EAGER PHILLIES FANS GAVE MARCELL OZUNA THE SHAFT

IBWAA members love to write about baseball. So much so, we've decided to create our own newsletter about it! Subscribe to Here's the Pitch to expand your love of baseball, discover new voices, and support independent writing. Original content six days a week, straight to your inbox and straight from the hearts of baseball fans.

Pregame Pepper

Did you know…

Rookie Wyatt Langford’s cycle, the first this season, was also the first for the Rangers in seven years . . .

Long-time Yankee Andy Pettitte had more wins (256) than Carl Hubbell, Bob Gibson, Whitey Ford, or Pedro Martinez — plus a record 19 wins in postseason play . . .

San Diego could save $90 million by dumping the contracts of Yu Darvish (5 years, $78 million left) and Jake Cronenworth (7 years, $80 million to go) . . .

The lame-duck Oakland A’s set a dubious major-league mark for the longest opening streak (28 games) before a starting pitcher got a win . . .

This is the 50th anniversary of Oakland’s third straight World Series win . . .

The Houston Astros were called Houston Colt .45s and then Houston Colts before the opening of the Houston Astrodome, the first domed ballpark and the first with artificial turf . . .

The year Hall of Famer Larry Walker hit a career-best 49 homers, he had more on the road (29) than at his home park, hitter-friendly Coors Field (20) . . .

Tampa Bay Rays president Erik Neander grew up in Oneonta, NY, near Cooperstown; swam in Otsego Lake; went to exhibition games at Doubleday Field; and got autographs during Induction Weekends.

Leading Off

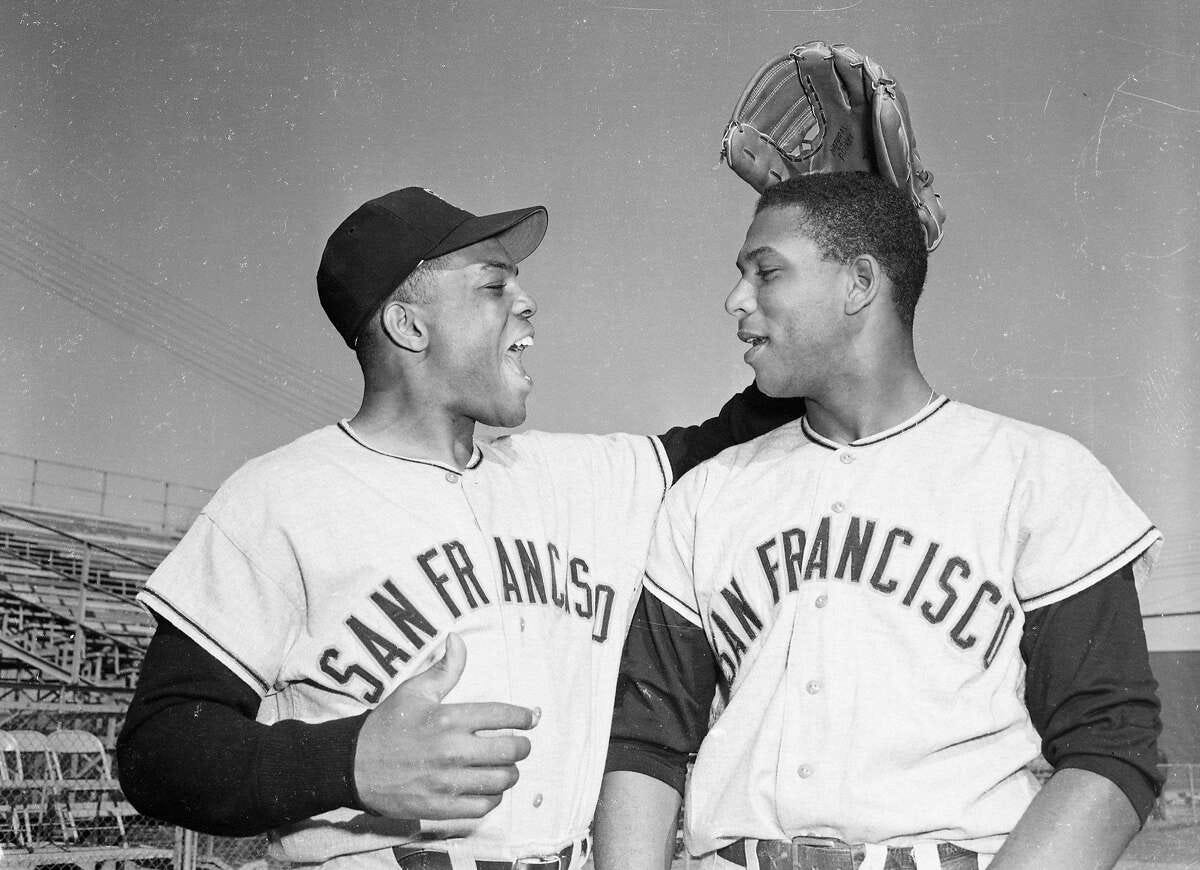

What Willie really left behind . . .

. . . namely, rip-roaring arguments over the greatest living former player

By Jeff Kallman

Three days before the Field of Dreams Negro Leagues tribute game at Birmingham, Alabama’s Rickwood Field, Hall of Famer Willie Mays expressed regret that his health would keep him from being on hand in the first professional ballpark in which he played. One day later, Mays went to the Elysian Fields at 93.

It took all of about a day before the arguments began. OK, that’s a slight exaggeration. But those arguments were (are) over who now is baseball’s greatest living player among those long retired from the field. The arguments never really cease, of course. But the death of a Mays provokes into overdrive the arguments themselves and the absurdities within.

When the father-and-son team operating Almost Cooperstown asked the question, I went against my better judgment and weighed in. I took what I thought a measured and sensible approach by naming the best according to a) their primary playing positions; and, b) their career wins above replacement-level player (WAR). That’ll teach me.

You sort of expect that to yield a swarm of those indignant about whom you left off the list, if not about WAR itself. The indignant often isolated a single statistical point or play highlight (don’t ask how many hoisted Pete Rose—who isn’t even close—merely by showing clips of his fabled headfirst slides) that didn’t take into even small account the player’s entire game.

Presuming Almost Cooperstown meant position players may have been a mistake, too, since many of the indignant weighed in with pitchers who generally belong in their own category. But these are the leading WARriors among the retired still alive who’ve played in the post-World War II/post-integration/night-ball era and are still among the living:

C—Johnny Bench.

1B—Albert Pujols.

2B—Rod Carew.

3B—Mike Schmidt.

SS—Álex Rodríguez.

LF—Barry Bonds.

CF—Ken Griffey, Jr.

RF—Reggie Jackson.

DH—Frank Thomas.

I knew there could be problems going in right there. Even if only a fool or a sports talk radio host might deny that one and all of them belong in conversations about the greatest of the great.

A-Rod’s value is almost entirely in his bat; he finished his career among the lowest-ranking shortstops for run prevention. Cal Ripken, Jr., who does not live by 2,131 alone, was a great hitter and the number three run-preventive shortstop of all. (Ahead of him: Hall of Famer Ozzie Smith; and, Mark Belanger, who played shortstop like an Electrolux but couldn’t hit if you held his family for ransom before every plate appearance he was allowed to make.*)

Carew was a great hitter and a not-so-run-preventive second baseman. (-5 below his league average.) In fact, he was more run preventive playing first base. (+10 above his league average.) Schmidt was great at run prevention playing third base, but there’s a guy about to be inducted into the Hall of Fame who was better. Hands up to everyone who knows it’s Adrián Beltré. (Beltre: +168; Schmidt: +129.) Now lower your hands if you weren’t surprised.

Mr. October had only five seasons in which he delivered above-league-average run prevention in right field. The most run-preventive right fielder among living former players is Jesse Barfield (+149), but he didn’t quite hit well enough to reach the Hall of Fame in an era where Hall voters still didn’t take defense as seriously as they should.

Pujols’s injury-instigated decline phase was a heartbreaker, but it didn’t ruin La Maquina for assessing him as a first baseman. He’s the absolute best-hitting first baseman of all, no questions asked . . . and, he’s the number three first baseman all time for run prevention (+100), behind should-be Hall of Famer Keith Hernandez (+120) and about-to-be-inducted Hall of Famer Todd Helton (+106).

What of those WARriors whose careers are seen as tainted by actual or alleged performance-enhancing substances? Simpler than you think. Both A-Rod and Barry Bonds built Hall of Fame cases well before they were suspected of having begun to indulge. Which means Bonds, the all-time WARrior among left fielders, still leaves Rickey Henderson (the greatest leadoff man of them all, but the Man of Steal wasn’t so run-preventive in left field) behind by two state lines.

Perhaps we should consider who excelled both ways the longest and at the toughest field positions. Griffey played a tough position but his injury-instigated decline was almost as sad as Pujols’s. Bench, Carew, and A-Rod changed positions for various reasons, two moving to third base and one (Carew) moving to first base. Schmidt got out when he realized his not-so-great 1988 was going to be the norm if he stayed in, retiring emotionally in May 1989 despite being among the National League’s RBI leaders at the time.Mays was just too overwhelming a choice as the greatest living baseball player before his death. After him, the choices are both enlightening and troubling, for the lack of absolute clarity.

The No. 2 all-around catcher who ever strapped it on (Bench) doesn’t always look that much better than the number one all-around third baseman who ever hit the field (Schmidt), but they both look a little better for playing tougher field positions than the number-one left fielder (untainted) who ever patrolled that corner. Round and round again.

Usually considered distinct from position players, the pitchers are a problematic bunch in their own right. Do you take the peak values of Sandy Koufax, Juan Marichal, or Pedro Martinez? The career values of Steve Carlton, Randy Johnson, Greg Maddux, or Nolan Ryan? The peak and career values of Roger Clemens, Johnson, Maddux, or Marichal? How much of their mound success was a question of the defenses behind them and the offenses supporting them in hand versus whatever they handled by themselves on the mound? Who’s the man you want most if your World Series gets to a seventh game? (Hint: They didn’t call him the Left Arm of God just to be cute.**)

Maybe the real legacy Mays left behind, other than his extra-terrestrial play on both sides of the baseball, is baseball’s second-oldest profession—rip-roaring arguments. Much like watching Mays play, those are the gifts that keep on giving. Because if you ask me the same question a year from now, my answers might be somewhat different, and just as non-conclusive.

* Mark Belanger actually holds one of the most dubious batting records in major league history—no player in the American League’s history was ever pinch hit for more than Belanger, who bore the indignity 333 times.

** Sandy Koufax’s peak was so off the chart that we don’t think of him in career value terms, ordinarily, since his first six seasons were those of a good, not great pitcher. But among those who pitched in the post-World War II/post-integration/night-ball age, Koufax’s 2.69 fielding-independent pitching rate—measuring the things pitchers can and do control—is the lowest among the still living. It isn’t close. The only starting pitcher with a lower FIP who’s played in the same era is the still-technically-active . . . Jacob deGrom.

_____

Jeff Kallman is an IBWAA Life Member who writes Throneberry Fields Forever. He has written for the Society for American Baseball Research, The Hardball Times, Sports-Central, and other publications. Jeff has lived since 2007 in Las Vegas, where he plays the guitar and writes music when not writing baseball. He remains a Met fan since the day they were born.

Cleaning Up

Ozuna Deserves All-Star Spot Over Any Phillies

By Dan Schlossberg

Here is where Marcell Ozuna ranked among all NL players as of June 28:

Batting average: .303 (sixth)

Home runs: 21 (second, trailing Ohtani)

OPS: .953 (third)

RBIs: 64 (second)

Phillies DH Kyle Schwarber didn’t rank among the NL’s top five in any of these categories. He ranked 13th with a .820 OPS.

A late rush from Philadelphia ballot-box stuffers helped Schwarber but sentiment against Ozuna still runs strong in the wake of his legal problems (suspensions and fines for alleged domestic violence in 2022 and driving under the influence a year later).

Fourteen months ago, it looked like Ozuna's career or at least his Braves tenure might be ending. He even batted .085 for the first month of the 2023 season.

Then, like a lightning bolt striking a tree, he caught fire.

Here’s where he ranks among all players since May 1, 2023:

Batting average: .299 (ninth)

Home runs: 59 (third, trailing Ohtani and Aaron Judge)

OPS: .963 (sixth)

RBIs: 162 (first)

But if the coaches and players vote the way the fans did, then Ozuna -- previously selected to the NL squad in 2016 and 2017 -- could find himself the year’s most significant All-Star snub.

The 33-year-old Dominican, who formerly played for the Miami Marlins and St. Louis Cardinals, broke into the majors in 2013. He delivered career peaks with 40 homers in 2024, 124 RBIs in 2017, and a .338 batting average in the virus-shortened season of 2020, when his 18 homers and 56 RBIs in 60 games led the National League.

Ozuna actually flirted with the elusive Triple Crown, last won in the NL by Joe Medwick in 1937, both in 2020 and earlier this season.

He should be headed to his third All-Star Game but first with the Braves, who signed him as a free agent on Jan. 21, 2020.

After sending eight players to the Midsummer Classic in Seattle last summer, Atlanta may have to settle for half as many. Starting pitchers Max Fried, Chris Sale, and Reynaldo Lopez are virtual locks to go, with Ozuna likely, and 40-year-old middle reliever Jesse Chavez a dark-horse candidate.

Philadelphia red will dominate the National League clubhouse in the wake of a concerted ballot-box stuffing campaign spurred by the team’s shameless promotion of sending fan favorites to the game rather than the most deserving players.

Thanks, MLB, for inspiring such shoddy conduct and depriving worthy players of their 15 minutes of fame.

Dan Schlossberg of Fair Lawn, NJ is the author of Home Run King: the Remarkable Record of Hank Aaron and more than three-dozen other baseball books, including collaborations with Ron Blomberg, Al Clark, and Milo Hamilton. His e.mail is ballauthor@gmail.com.

Timeless Trivia: Orlando Cepeda Carried a Big Bat

“Hank [Aaron] could do it all, and do it as well as anyone. He often does not get the full credit he deserves for being such a superb all-around player. He could do all the things Willie Mays could do, he just wasn’t as flashy. Just ask the people who played baseball with Hank day in and day out. They’ll tell you what a complete baseball player Hank really was.”

— The late Orlando Cepeda in his 1998 autobiography Baby Bull

The second black Puerto Rican (after Roberto Clemente), Cepeda was 1958 National League Rookie of the Year and later its MVP . . .

The Baby Bull, also nicknamed Cha Cha, was an All-Star 11 times . . .

He was the first player to sign a contract (with the Boston Red Sox) to serve as a full-time designated hitter . . .

What goes around comes around: in 1966, the Giants traded Cepeda to St. Louis for Ray Sadecki. Three years later, the Cardinals sent Cepeda to Atlanta for Joe Torre. In 1974, St. Louis swapped Torre to the New York Mets for Sadecki . . .

Cepeda and Torre won MVP awards with the Cardinals in 1967 and 1971 . . .

In 1999, Cepeda was elected to the Hall of Fame by the old Veterans Committee.

Know Your Editors

HERE’S THE PITCH is published daily except Sundays and holidays. Benjamin Chase [gopherben@gmail.com] handles Monday and Tuesday editions, Elizabeth Muratore [nymfan97@gmail.com] does Wednesday and Thursday, and Dan Schlossberg [ballauthor@gmail.com] edits the weekend editions on Friday and Saturday. Readers are encouraged to contribute comments, articles, and letters to the editor. HTP reserves the right to edit for brevity, clarity, and good taste.