He's-no-Ángel Hernández Packs It In

DAN'S ADVICE: DON'T LET THE BARN DOOR SMACK YOU ON YOUR WAY OUT

Pregame Pepper: Good News & Bad News

The Yankees lead the majors in walks and home runs, the Rays have the most infield hits, the Reds have the most stolen bases, and the Royals have the most bunt hits . . .

The Rockies have the worst ERA, Mets pitchers have issued the most walks, and the Pirates have the most blown saves . . .

Not surprisingly, the Oakland-Sacramento-Las Vegas team is averaging an MLB-worst 6,297 fans per game at the delapidated Oakland Coliseum . . .

With Toronto struggling, trade rumors have enveloped several players, with both the Dodgers and Braves reportedly bidding for Bo Bichette . . .

Washington’s Eddie Rosario, 2021 NL Championship Series MVP for the Braves, received an ovation from a Memorial Day crowd before his first at-bat for a visiting team at Truist Park but silenced the crowd with an RBI double against Charlie Morton. Rosario will always be remembered in Atlanta for his 2021 NLCS, including 14-for-25 (.560) with a double, triple, three homers, and nine RBIs against the Dodgers.

Leading Off

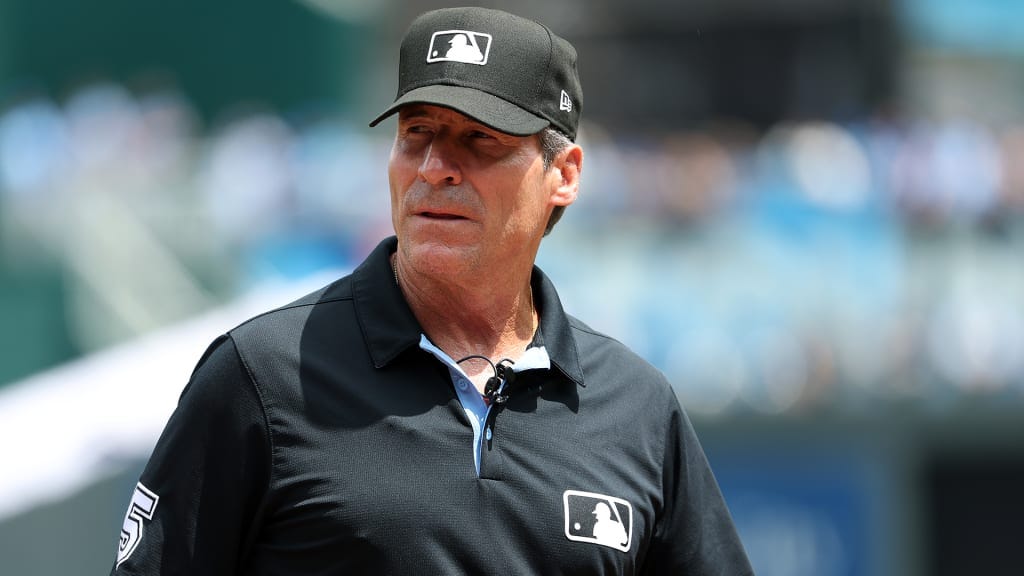

The Angel of Doom was the face of baseball?

An ESPN host said so. We should say ‘don’t even think about it’

By Jeff Kallman

The news broke on Memorial Day that baseball’s most controversial umpire, a designation you really have to earn, was retiring after negotiating a settlement with MLB. It went viral in better than record time. And it happened days after The Athletic published a deep and nuanced dive into the man versus the too-well-earned professional rep.

For what seemed half-eternity, Ángel Hernández was the No. 1 nuisance aboard baseball’s 10 least-wanted umpires list, and he’d gotten there the old-fashioned way —he earned it. The Angel of Doom earned it with flagrantly bad pitch calls, a kind of smirking eagerness to stir confrontations, and a non-existent sense that he might want to admit he was wrong when confronted with the evidence.

When it turned out USA Today’s Bob Nightengale wasn’t kidding around when he broke the news, it seemed 85-90 percent of the mood was happy-days-are-here-again. Rob Manfred may be baseball’s Public Enemy Number One as often as not, but Hernández probably had a tight grip upon Public Enemy Number One-A. Videos of his worst seemed going almost as viral as the news itself.

But then ESPN Radio host Evan Cohen threw a morning-after stink bomb into the ding-dong-the-witch-is-dead party. Cohen’s response to the Angel of Doom’s departure was, essentially, not so fast, are we really sure this is good for the game, because, you know, Hernández’s retirement removes the face of baseball?

Cohen’s co-host Chris Canty shot that one down swiftly: “It’s great for baseball,” Canty said definitively. “We don’t need to have the umpires being the story around every single game. Nobody paid money to come see you, Angel . . . It ain’t about the umpires, it’s about the players on the field. So, I’m glad that Ángel Hernández is gone.” But maybe not swiftly enough.

There are those who do think the umpires are the game’s faces. One of them was the late Hall of Fame umpire Doug Harvey, sort of, in his memoir titled (wait for it) They Called Me God: “We’re the backbone of the game, the game’s judge, jury, and executioner. Without us, there’s no game.”

“We should never know the umpire’s name,” said Cohen’s co-co-host Michelle Smallmon. Well, that’s not entirely true. When I was watching baseball ardently as a boy in and around New York, I knew a lot of umpires’ names, thanks to the diligence of the original Mets broadcast team of Lindsey Nelson, Bob Murphy, and Ralph Kiner, plus those manning the ancient network Games of the Week.

I was just as familiar with such umpires as Harvey, Al Barlick, Ken Burkhardt, Shag Crawford, Augie Donatelli, Chris Pelekoudas, Ed Sudol, Harry Wendelstedt, and Lee Weyer, as I was with Henry Aaron, Dick Allen, Ernie Banks, Yogi Berra, Roberto Clemente, Bob Gibson, Sandy Koufax, Juan Marichal, and Willie Mays.

(We could have just as much fun with their names, too. If we thought Weyer got one wrong, which wasn’t very often, actually, we had mad fun calling him Weyer Fraud. Al Garlick, Shaggy Dog Crawford, and Ed Pseudo got a lot of play, too. Just kidding, gentlemen.)

But I don’t remember any of those umpires becoming even a twentieth as infamous for malpractice as Hernández became. Those umps were the presumed adults in the room and behaved that way most of the time.

It wasn’t easy when confronted with such instigators as Leo Durocher, Billy Martin, and Earl Weaver. (That sonofabitch called me names that would get a man killed in some places. And that was on days I didn’t throw him out. —The late Steve Palermo, on Weaver.)

It was child’s play when confronted with maturities such as Gil Hodges or Walter Alston. They may have been human and may have made their mistakes, but those umps never really seemed to suggest up yours! was the proper response to being called out for them.

Doug Harvey’s smug pronunciamento to one side, most of those umps never once thought of themselves as the faces of baseball. At least, not publicly or in cold print. The owners had to learn the hard way (and often still do) that baseball’s faces were (are) the players on the field whom they could no longer bind and keep as chattel after 1975.

Let a Donatelli or a Pelekoudas go on the record thinking their breed were baseball’s faces, and you couldn’t set up a road block big or fast enough to stop them being run out of town. And maybe off the continent.

Too many umpires today behave professionally as though such road blocks couldn’t (wouldn’t dare!) exist. They have reason enough. Baseball’s government has long enough been wary of trying to impose accountability upon umpires within reasonable equality to that imposed upon players, coaches, managers. So has their union.

The World Umpires Association, the phoenix that arose from the self-immolating ashes of the original Major League Umpires Association (which immolated itself because of an attempt at accountability), is just as wary of considering that, just maybe, those among their clients who soil things for the comparative many should be made to answer when their errors become flagrant and voluminous enough.

Hernández wreaked enough damage upon baseball without going into retirement leaving even one observer mourning the loss of the face of the game. But if you’re going to be foolish enough to think an umpire is baseball’s face, consider this: Could we talk the Topps, Panini, and Upper Deck people into producing umpire cards?

Imagine baseball cards with the umps and their mugs on the front and their true stats on the rear. Where fans and others could see pocket evidence that they weren’t seeing things at or in front of the games. The stats on the back would (should) surely include accuracy rates, percentages of wrongly called balls and wrongly called strikes, ejections, and calls overturned upon review.

You can only imagine an Ángel Hernández card now. (Fair play: He’s said to be so nice off the field that he might have gotten a perverse kick out of being asked to sign one.)

But take heart. We still have the C.B. Bucknors, Phil Cuzzis, Laz Diazes, Manny Gonzalezes, Alfonso Marquezes, and Hunter Wendelstedts among us.

If baseball’s government and the umpires’ union won’t entertain accountability, maybe a baseball card maker could give them a big shove in that direction.

Jeff Kallman is an IBWAA Life Member who writes Throneberry Fields Forever. He has written for the Society for American Baseball Research, The Hardball Times, Sports-Central, and other publications. He has lived in Las Vegas since 2007, where he plays the guitar and writes music when not writing baseball. He remains a Met fan since the day they were born.

Cleaning Up

Goodbye and Good Riddance to Angel Hernández

By Dan Schlossberg

Umpires are supposed to be anonymous, impartial arbiters who serve as the policemen of the game.

For the most part, that’s true, though long-time umps like Al Clark (26 years in the majors) insist the men in blue are actually the third team on the field — and worth watching as they communicate with each other and take different positions depending upon game situations.

Occasionally, umpires gain recognition. Doug Harvey was so serious, so resolute, and so professional that his nickname was “God.” Bill Klem was so good at calling balls and strikes that he worked exclusively behind the plate for the last 14 years of his career. And Emmett Ashford, who became the first black umpire in 1966, bellowed his strike calls for the whole stadium to hear.

And then there was Ángel Hernández, who never met a bad call he didn’t like.

He did the baseball world a favor when he retired the day after Memorial Day.

Universally regarded as the worst umpire in baseball, his lack of ability as a balls-and-strikes guy was challenged only by the late Eric Gregg.

Let’s put it this way: Chipper Jones once said he refused to watch any Braves game in that included Hernández behind the plate.

On April 12 of this year, to cite one recent example, Rangers rookie Wyatt Langford struck out on three straight called strikes that clearly missed the zone, with seven other outside pitches in the same game also called strikes by Hernández.

“I have decided that I want to spend more time with my family,” the Cuban native said in a statement. “Needless to say, there have been many positive changes in the game of baseball since I first entered the profession. That includes the expansion and promotion of minorities. I am proud that I was able to be an active participant in that goal while being a Major League umpire.”

Hernández, an umpire for 33 years, twice sued Major League Baseball for alleged discrimination regarding his failure to win prestigious appointments to umpire post-season games. He lost both cases, including the most recent in 2017 (and a subsequent appeal).

The 62-year-old arbiter, who last officiated in a World Series game 19 years ago, worked his last regular-season game on May 9. He spent the past two weeks working out a financial settlement with MLB.

“Starting with my first Major League game in 1991, I have had the very good experience of living out my childhood dream of umpiring in the major leagues,” he said. “There is nothing better than working at a profession that you enjoy. I treasured the camaraderie of my colleagues and the friendships I have made along the way, including our locker room attendants in all the various cities.”

Apparently, he liked them better than they liked him.

A lightning rod for controversy, he was widely considered the worst umpire in the game by players, managers, media members, and fans.

That poor reputation dates back to player polls by Sports Illustrated in 2006 and 2011 ranking him as the third-worst umpire and an ESPN poll in 2010 in which 22 per cent of the respondents fingered Hernández as the worst man in blue.

Hernández began his career as an umpire at the age of 20 in the Florida State League and became a full-time MLB ump in 1993.

Timeless Trivia: San Diego’s Super Bullpen

Rookie San Diego reliever Jeremiah Estrada, 25, lowered his ERA to 0.55 Tuesday night by fanning his 13th hitter in a row — a major-league record. The once-wild righty from nearby Palm Desert, CA went into this season with 16 1/3 innings of big league experience but fanned 18 of the first 21 hitters he faced . . .

The bullpen tandem of Estrada and Roberto Suarez could both be on their way to Texas for the July 16 All-Star Game and could garner Cy Young Award votes too . . .

The Padres have already had one of their relievers (Mark Davis) win a Cy and three others (Rollie Fingers, Goose Gossage, and Trevor Hoffman) reach the Baseball Hall of Fame . . .

Hard to believe erstwhile All-Star Josh Hader, now with Houston, is just a distant memory in San Diego . . .

Estrada consistently throws in the upper 90s, blending his heater with a novel pitch he calls a “chitter,” a cross between a change-up and split-fingered fastball.

Know Your Editors

HERE’S THE PITCH is published daily except Sundays and holidays. Benjamin Chase [gopherben@gmail.com] handles Monday and Tuesday editions, Elizabeth Muratore [nymfan97@gmail.com] does Wednesday and Thursday, and Dan Schlossberg [ballauthor@gmail.com] edits the weekend editions on Friday and Saturday. Readers are encouraged to contribute comments, articles, and letters to the editor. HTP reserves the right to edit for brevity, clarity, and good taste.