Hank Greenberg Was A Hero On And Off The Field

PLUS: BASEBALL AND THE BRAVES WILL MISS SUPER-FAN JIMMY CARTER

IBWAA members love to write about baseball. So much so, we've decided to create our own newsletter about it! Subscribe to Here's the Pitch to expand your love of baseball, discover new voices, and support independent writing. Original content six days a week, straight to your inbox and straight from the hearts of baseball fans.

SPECIAL NEW YEAR’S OFFER FOR OUR READERS

GET HERE’S THE PITCH 2025

Selected and edited by Dan Schlossberg

(215 pp, $24.95)

This first annual collection of 35 great baseball stories, analysis, memories, and trivia for the baseball fanatics on your gift list (including you) is available now for $24.95 at

http://www.actasports.com

But subscribers to this newsletter get 10% off on one copy or 20% off on two or more copies by calling 800-397-2282, talking to a real live person (not an AI robot), and ordering directly from the publisher. Offer good only through February 1, 2025!

Pregame Pepper

Did you know…

Few fans have heard of Xavier Edwards, the switch-hitting shortstop of the Miami Marlins, but in 2024 he hit for the cycle July 28 and then had three triples in one game Sept. 27 — the first time that happened since Yasiel Puig did it in 2014 . . .

Edwards, 24, not only did it from both sides of the plate but collected four RBIs too with his 4-for-6 performance in Toronto, becoming the fourth player in 100 years to do all those things in the same game . . .

Charlie Morton, 41, wants to keep pitching but only if he can find a team that trains close to his Bradenton, FL home . . .

That means the Rays, Pirates, Orioles, and Braves are his top choices — but will he take a cut from the $20 million Atlanta paid him last season? . . .

During the 13 years they played together, Eddie Mathews hit more home runs than Hank Aaron. Both peaked with 47-homer seasons, the Braves franchise record before Andruw Jones (51) and later Matt Olson (54) passed them . . .

Speaking of Jones, Sarah Langs of MLB.com wrote a brilliant end-of-the-year essay recommending his long-overdue enshrinement into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Leading Off

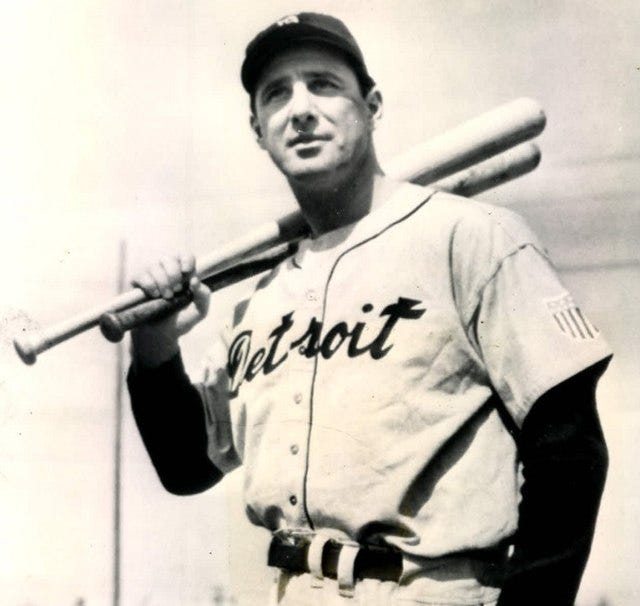

Hank Greenberg: A Hero from Another Time

By Bill Pruden

While baseball’s history is central to much of its appeal, there is a growing disconnect between the sport’s hallowed past and its media-dollar-driven present.

Indeed, as the new year opens and the hope so central to each new season comes to the fore, I find myself torn between honoring the game’s past or bemoaning its present.

Consider the case of Blake Snell, the high-priced free agent the Los Angeles Dodgers added to their roster this winter.

What does it say about the modern game that Snell — who will pitch in the shadow of Dodgers’ Cy Young Award starters Don Newcombe, Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, Fernando Valenzuela, Orel Hershiser, and Clayton Kershaw — has two Cy Young Awards of his own but only a single complete game on his major-league resume?

But rather than belabor the modern changes that both befuddle and distress me, I want to start the new year by harking back to another time to write about a man, born on New Year’s Day 1911, who struck fear in the hearts of the best hurlers of his day while embodying the characteristics that were at the heart of baseball’s place as the national pastime.

That man is Hank Greenberg.

Born in the Bronx, not far from Yankee Stadium, he was the third of four children of Jewish immigrants who had come to the US from Romania. His parents intended to name him Hyman only to have the birth certificate mistakenly list him as Henry.

He was an outstanding all-around athlete at James Monroe High School, where he starred in basketball — leading the team to the city championship -- track & field, soccer, and of course, baseball, his favorite.

At 18, the 6-foot, 4-inch Greenberg was coveted by the New York Yankees, but Hank recognized the obstacle that the team’s incumbent first baseman, Lou Gehrig represented. After turning down the home team’s offer, he accepted a scholarship to New York University. But he traded books for baseball when he signed with Detroit at the end of his freshman year.

In a token pinch-hit at bat for the Tigers –- he popped up to second against Red Ruffing on September 14, 1930 against the Yankees but spent 1930-1932 in the minors. The New York native played for teams in Hartford, Raleigh, Evansville, and eventually Beaumont, Texas where in 1932 he hit 39 home runs, drove in 131 runs, and won the MVP Award while leading the team to the Texas League championship.

Upon reaching the majors in 1933, Greenberg was an immediate star, hitting .301, the first of eight .300 seasons in a row. While he only hit 12 home runs (in 117 games) he still drove in 85 runs.

With the exception of 1936, when a wrist injury limited him to 12 games, from 1933 through 1940 he hit 246 home runs, topped by 58 in 1938. Three times he led the American League with RBI totals of 150, 168, and an AL-record 184 (tied with Lou Gehrig) in 1937.

With war raging in Europe, and the US having instituted a military draft, in October of 1940, he became the first major-leaguer to register for the draft. Nineteen games into the 1941 season, Greenberg entered the Army, only to be honorably discharged on December 5. In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, he reenlisted, serving in the US Special forces and doing time in the China/Burma/India theater. Overall, Greenberg served a total of 47 months, longer than any big-league player.

Returning to the Tigers in June 1945, he picked up where he had left off, hitting .311 with 13 homers and 60 RBIs in 78 games, adding offensive punch to a team headed by pitching Triple Crown winner Hal Newhouser. It went on to defeat the Chicago Cubs in the World Series.

Though Hammerin’ Hank’s average dipped to .277 in 1946, he led the American League with 44 home runs and 127 RBIs as the Tigers finished second behind the Boston Red Sox.

A year later, Greenberg and the Tigers ensnared in a major contract dispute. When he decided to retire rather than take a pay cut, the team sold his contract to the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Desperate to have Greenberg play, the Pirates made him baseball’s first $100,000 ballplayer.

His switch to the National League came at a fortuitous time, as 1947 was Jackie Robinson’s rookie year. As someone who had endured his own share of bigotry because of his religion, Greenberg publicly welcomed Robinson — and privately told him he had similar troubles and would help keep his head above water (that promise, conveyed the first time they met at first base, was painfully omitted from the film 42).

Robinson acknowledged and appreciated Greenberg’s support.

Beyond his own on-field contributions of 25 home runs and 74 RBIs, Greenberg mentored promising Pittsburgh rookie Ralph Kiner, a slugger who would go on to a Hall of Fame career of his own thanks to seven straight home run crowns.

The 1947 season proved to be Greenberg’s last. He finished with 331 home runs and drove in 1,274 runs while compiling a career batting average of .313 and a slugging average of .605. He was American League Most Valuable Player in 1935 and 194 and reached the Hall of Fame in 1956.

And he did it all while missing three full seasons and parts of two others because of his wartime service in the Army.

Greenberg remained in baseball after his retirement as a player.

He served in the front office of both the Cleveland Indians and the Chicago White Sox and was known for his advocacy of African American players.

Years later, Greenberg was one of the few players who publicly supported Curt Flood’s challenge to MLB’s reserve clause, even testifying in court on Flood’s behalf.

That wasn’t surprising to those who had watched Hank Greenberg over the years; who had seen him sit out games during Yom Kippur (the Jewish Day of Atonement); or knew of his lengthy military service record.

Such actions were simply a reflection of who he was: a model of the best baseball could offer — on and off the field — at a time when the game was truly the undisputed national pastime.

Bill Pruden is a high school history teacher whose love for baseball history was sparked as a 7-year-old when he witnessed Roger Maris hitting his 61st home run at Yankee Stadium in 1961. He has been writing about the game -- primarily through SABR-sponsored platforms -- for about a decade. His email address is courtwatchernc@aol.com.

Cleaning Up

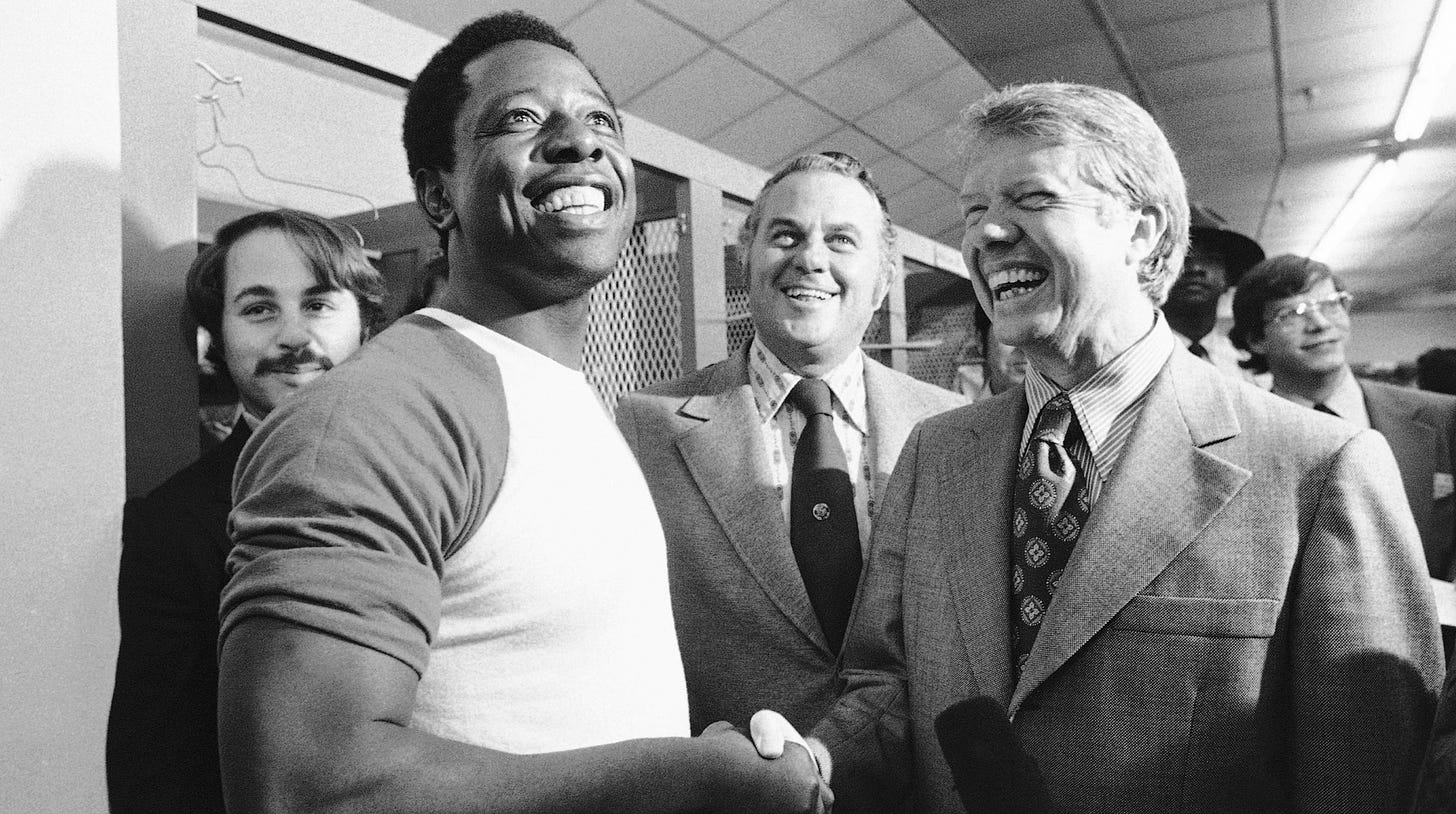

Jimmy Carter Loved Baseball And The Braves

By Dan Schlossberg

Two years before he ran for President, Jimmy Carter was in Atlanta Fulton County Stadium to witness baseball history.

Then the Governor of Georgia, Carter came to the ballpark on April 8, 1974 as he had so many times before: wife Rosalynn on his arm, red-and-blue Braves cap on his head.

Carter was in the clubhouse in previous September when Hank Aaron was closing in on Babe Ruth’s home run record. He even interrupted an interview this reporter was conducting with Aaron during a rain delay (the game was eventually cancelled and not made up, forcing the slugger to wait in limbo for seven more months).

That plate read “HR 715” and prompted a great Carter quip: “They gave him the Cadillac. I gave him the tag.”

The car, along with other gifts, came from the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce but the frugal Carter was front-and-center with his pertinent but much more inexpensive contribution.

The 39th president, who died at age 100 just before New Year’s Eve, was always contributing to the Braves and to the game.

As governor and later as president, he hosted softball games involving his media contingent — and followed with a Southern-style barbecue — at his home in rural Plains, GA.

A one-time peanut farmer, Carter later became a nuclear engineer in the U.S. Navy. He was married for — are you ready for this? — 77 years. No major-league manager ever lasted that long (Connie Mack holds the record at 53).

When he wasn’t throwing out the first pitch before a game, Carter was cheering for the team from the Owner’s Box just to the right of home plate. Ted Turner was often there too, along with Jane Fonda and Rosalynn. The Carters made it a point to stay awake for the television cameras.

Carter, by the way, had better control than many of the Braves’ pitchers. When he threw out that pitch from the mound, it was always a perfect strike.

Although Barack Obama, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, the two George Bushes, and the ambidextrous Harry S Truman were baseball fans too, none was as rabid as Jimmy Carter. He truly loved the game — and would have made a fine Commissioner if he weren’t always galavanting the globe in the name of world peace.

He will always be remembered as a friend of the game and a personal friend of Hank Aaron’s. They even went on European ski vacations with their wives.

After he reached the White House, Carter had Henry as his honored guest in the Oval Office. He wasn’t the first wise Henry to sample the sofa — Kissinger beat him to it —but he probably had a better year.

Upon his passing, the Braves issued condolences. "The Atlanta Braves are deeply saddened by the passing of President Jimmy Carter," the team said in a statement. "President Carter was a testament to the best America, and Georgia, can produce. He served both his country and home state with honor his entire life.

"While the world knew him as a remarkable humanitarian and peacemaker, we knew him as a dedicated Braves fan and we will miss having him in the stands cheering on his Braves. Our deepest condolences to his children, grandchildren and great grandchildren."

Here’s The Pitch weekend editor Dan Schlossberg of Fair Lawn, NJ is national baseball writer for forbes.com, columnist for Sports Collectors Digest, and contributor to Memories & Dreams, USA TODAY Sports Weekly, various SABR publications, and a myriad of other outlets. His books include two Hank Aaron biographies. Want a book talk? Contact Dan via email ballauthor@gmail.com.

Timeless Trivia: Aaron, Mathews, And Homers

Hank Aaron and Eddie Mathews shared the Braves franchise record of 47 home runs in a season until Andruw Jones (51) and later Matt Olson (54) broke it . . .

Aaron and Mathews were two of the four straight Braves hitters who homered against the Reds in 1961 . . .

Mathews hit 370 home runs by age 30, topping Aaron’s 342 by the same age . . .

His 47-homer season for the Milwaukee Braves in 1953 stopped Ralph Kiner’s streak of seven straight home run titles . . .

Aaron reached the majors a year later but hit only 13 in his rookie year . . .

From 1952-59, Mathews led the majors with 299 home runs, topping 40 four times . . .

Mike Schmidt eventually erased the Mathews marks for home runs by a third baseman in a season and in a career.

Know Your Editors

HERE’S THE PITCH is published daily except Sundays and holidays. Benjamin Chase [gopherben@gmail.com] handles the Monday issue with Dan Freedman [dfreedman@lionsgate.com] editing Tuesday and Jeff Kallman [easyace1955@outlook.com] at the helm on Wednesday and Thursday. The last original editor, Dan Schlossberg [ballauthor@gmail.com], edits the weekend editions on Friday and Saturday. Former editor Elizabeth Muratore [nymfan97@gmail.com] is now co-director [with Benjamin Chase and Jonathan Becker] of the Internet Baseball Writers Association of America, which publishes this newsletter and the annual ACTA book of the same name. Readers are encouraged to contribute comments, articles, and letters to the editor. HtP reserves the right to edit for brevity, clarity, and good taste.