Does Unbanning Rose and the Black Sox Pass the Smell Test?

And, is Rob Thompson still the best man to manage the Phillies?

Pregame Pepper

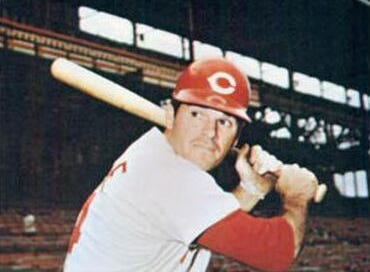

One of the game’s greatest players has engaged in a variety of acts which have stained the game, and he must now live with the consequences of those acts. By choosing not to come to a hearing before me, and by choosing not to proffer any testimony or evidence contrary to the evidence and information contained in the report of the special counsel to the commissioner, Mr. Rose has accepted baseball’s ultimate sanction, lifetime ineligibility.

. . . [L]et there be no doubt or dissent about our goals for baseball or our dedication to it. Nor about our vigilance and vigor—and patience—in protecting the game from blemish or stain or disgrace. The matter of Mr. Rose is now closed. It will be debated and discussed. Let no one think that it did not hurt baseball. That hurt will pass, however, as the great glory of the game asserts itself and a resilient institution goes forward. Let it also be clear that no individual is superior to the game.

—A. Bartlett Giamatti, baseball commissioner, announcing Pete Rose’s banishment for gambling on the game, August 1989.

Leading Off

Rose is Unbanned. (The Black Sox, Too.)

Why does it flunk the proverbial smell test so far?

By Jeff Kallman

March: Donald Trump harrumphs that by thunder he’s going to hand the late Pete Rose a pardon because MLB lacked “the courage or the decency” to put him into the Hall of Fame. The fact that the Hall of Fame makes its own rules on ballot eligibility, including the rule that barred Rose from Hall ballots, never crossed Mr. Trump’s mind.

The further fact that a president’s pardon power doesn’t include overturning, essentially, an enterprise’s employee’s banishment for written-rules cause, didn’t cross the mind of a president to whom the law is his to bend, shape, contort, distort, or snort. (And if you don’t like it, tough you-know-whatties.)

16 April: Commissioner Rob Manfred had a meeting with Mr. Trump. Said before, saying again: Mr. Manfred, like Mr. Trump, is a man who seems too often to point the way to right reason by standing athwart it.

“I met with President Trump two weeks ago, I guess now,” said Manfred, as cited by The Athletic on 29 April, “and one of the topics was Pete Rose, but I’m not going beyond that. He’s said what he said publicly, I’m not going beyond that in terms of what the back and forth was.”

What a pair: A word-salad baseball commissioner in a sit-down with a word-salad president. Or was that a word-salad president in a sit-down with a word-salad baseball commissioner? Whichever you prefer, what came next was almost predictable except for the actual moment it would be made so.

28 April: As Manfred told The Athletic for that same 29 April article, he decided on this date that he would rule on Rose’s reinstatement, a decision he made about three months after Rose’s family petitioned him to reinstate him posthumously.

Reality: Once Manfred made that decision, and let it be known publicly that he would rule on Rose, the only question remaining was when, not if, Manfred would say, yes, folks, Rose is being reinstated to baseball. (If you think otherwise, folks, I know some tariff-paying penguins who’d like to sell you timeshares on their Heard and McDonald Islands.)

That when turned out to be yesterday. The day before the Reds planned to hold Pete Rose Day, conveniently enough.

Manfred to the Baseball Writers Association in 2022: “I believe that when you bet on baseball, from Major League Baseball’s perspective, you belong on the permanently ineligible list.” That was then: Manfred, in essence, was upholding The Rule, which mandates permanent banishment for betting on games in which you’re supposed to perform whether as a player, a coach, or a manager, and does. not. distinguish. whether you bet on your team to win or lose.

Manfred, on Tuesday, announcing Rose’s reinstatement: “In my view, a determination must be made regarding how the phrase ‘permanently ineligible’ should be interpreted regarding Rule 21 [the gambling rule under which Rose was banished]. Obviously, a person no longer with us cannot represent a threat to the integrity of the game.”

That also means that invited in from the cold are the ghosts of the banished 1919 Black Sox, only two of whom (Shoeless Joe Jackson, Eddie Cicotte) would have been considered viable Hall of Fame candidates if not for their taints. Also, such others among the banished deceased as six players, one coach, and even one owner. (William Cox, Phillies, forced to sell his team and banned for life, after either his freshly-fired manager Bucky Harris or Harris friends blew the proverbial whistle on Cox placing bets on Phillies games.)

Manfred’s about face, whether entirely his own or after an arm-twisting by a particularly corrupt and witless American president, doesn’t mean that Rose is going to be hustled into Cooperstown post haste. Manfred may sit on the Hall’s board (a perk of his office) but it doesn’t mean he can decide the Hall should start prepping for Rose’s induction—or order it.

Rose’s partisans (they remain legion enough) may not like it after getting one thing for which they’ve hungered for longer than Rose himself played baseball, but it will take the next meeting of the Classic Baseball Era Committee to vote on whether to enshrine him—if the Hall’s Historical Overview Committee puts Rose on the Classic Era ballot in the first place. The Classic Era Committee won’t meet again until near the end of 2027.

We are left, then, to contemplate the prospect of three men who stained the game they professed to love being handed the game’s highest honour, even posthumously. We should contemplate even more the prospect that a baseball commissioner with a passion for tinkering with baseball’s rules and play as a childlike scientist given unlimited laboratory access has just rendered The Rule meaningless.

The Rule was provoked into being after the Eight Men Out proved the culmination of a gambling infestation plaguing baseball for well before one of their rank approached gamblers about a World Series fix. The Rule remains posted vividly in every professional baseball clubhouse. It was there before Pete Rose first entered one, it remained after he last left one, and it still remains.

For now.

Once Manfred had a sit-down with a President Trump who made a point of bellowing publicly that he believes Rose was done dirty, however erroneously, was it inevitable or predictable that the commissioner would lift Rose’s permanent banishment one way or another? Did Manfred act entirely on his own? Did he get a presidential threat of one or another kind to his backside unless he un-banished Rose?

This business is flunking the proverbial smell test worse than any student ever flunked logic.

Jeff Kallman edits the Wednesday and Thursday editions of Here’s the Pitch. You can reach him at easyace1955@gmail.com.

Cleaning Up

Assessing Rob Thompson

Is the Phillies’ skipper one of baseball’s best?

By Russ Walsh

In a 2023 article in Esquire, sportswriter Joe Posnanski called managing a baseball team “the most mysterious coaching job in all of sports.” The gist of the article was that defining why Bruce Bochy (Rangers) might be the best manager of all time, or why Craig Counsell (Cubs) might be worth $40 million, is a daunting task.

Managing a baseball team is subject to the fates more than other sports. Will your hottest hitter come up in the right spot? Will your starting pitcher keep you in the game? What key injury will foil all your plans?

As much as managers get criticized for in-game decisions—putting in a pinch hitter, failing to make a defensive change, pulling the starter for a middle reliever—managers only really impact the game in progress on the margins.

Certainly, what makes for a good manager is more than the won/loss record. While the won/loss record may be the immediate cause of a firing (ask the Pirates’ Derek Shelton, or the Rockies’ Bud Black), winning percentage is a weak criterion for managerial excellence.

Bochy, widely considered the best, has a losing record, 2189-2206 at this writing. Terry Francona, on everyone’s list as a top manager was 285-363 in his three seasons with the Phillies, who fired him and watched him build a winner in Boston four years later. Francona was a great manager with a poor team in Philadelphia. When he had the right players, he became a legendary manager.

To find out what makes a good manager, then, go deeper.

It is more about building a winning culture than winning today’s game. It is more about taking the media heat off your players than calling for a hit and run. It is more about managing the relationships of a group of highly paid athlete’s in a sport built, most of the time, on failure. It is more about organization and preparation than moment-to-moment decision making.

Ultimately, it is about putting your team in the best position to win. If that is the criteria, then the Phillies’s Rob Thompson deserves to be where he is rarely found—on the list of the very best managers in major league baseball.

Under their previous manager, Joe Girardi, a good manager with a proven record of success, the Phillies were a star-studded, underachieving, .500 baseball team. From the moment the unassuming Thompson took over, the Phillies took off. The 2022 Phillies earned a wild card spot in the playoffs by going 65-46 under Thomson and then made an improbable run to the World Series, before losing the series to the Houston Astros in six games.

The team has improved during the regular season each season under Thomson since then, going 90-72 in 2023 and 95-67 last year. Each of those years, of course, ended in playoff disappointment. And there is the rub. The failure to make it back to the World Series and win it has placed Rob Thomson on the hot seat.

It shouldn’t. The playoffs are a crap shoot. It is often the hottest team and not necessarily the best team that advances. But when you are spending big money on a team of supposed All-Stars, the owner and the fans expect to go all the way to the top. Just a week ago, Bleacher Report’s Zachary D. Rhymer put Thompson on the “honorable mention” list for managers ripe for firing saying, “if progress continues to stall or even reverses, a new leader could be needed.”

Moving on from Thomson would be a mistake.

Phillies fans tend to like fiery, in- your-face managers in the Dallas Green and Larry Bowa mode, but such managers don’t have a great track record. Green was successful (with a team that should have won at least twice before he took it over) despite his abrasive style, not because of it. He lasted only two seasons on the Phillies’s bench.

Bowa toned down his act and did a solid job with a young Phillies team, until he had a clash with the best Phillie of the time, Hall of Famer Scott Rolen. It is hard to imagine the current Phillies crop of wealthy veterans welcoming a martinet-style manager into the fold.

Thompson has little charisma. He doesn’t call attention to himself. His post-game press events can be snoozers. The closest he’ll come to criticizing his players in public is to say, “He made a mistake; he knows it,” or “Yes, we’ll speak to him about that.” The lack of big personality might actually be an asset on a team that features Bryce Harper, Nick Castellanos, and Kyle Schwarber.

The players carry the charisma load, and Thompson has their back.

I’ve watched Thompson closely for three years now. His forte, it seems to me, is playing chess while the fans are calling for checkers. That sometimes means making decisions early in the season that don’t seem designed to win the game on that day. Thompson is a master of the long game.

If he feels he has overused his leverage relievers, he may bring a back-of-the-bullpen guy in for a leverage situation, saving his best guys, because he knows he will need those leverage relievers to be healthy down the road. The same goes for his core position players. It may mean sticking with a slumping Alec Bohm, over a red-hot Edmundo Sosa, because he knows he is not winning pennants with Edmundo Sosa as his third baseman, and that showing confidence in a proven hitter like Bohm will likely ultimately pay off.

As any check of social media feeds will tell you, this style of saving his best for when he really needs it can drive fans crazy. But it has also been shown to be effective.

Ultimately, of course, Thompson must satisfy the ownership. Phillies owner John Middleton has invested a lot of money into “getting his f***king [World Series] trophy back.” The Phillies are trying to win this year with, essentially, the same team that failed to win the last three years.

It seems harsh to judge Thompson for the upper management decisions, but if the Phillies fail to make the playoffs this year or fail to advance past the first two rounds, Thomson’s head may be on the chopping block. But firing Thomson would be a mistake.

One of the key factors of any successful enterprise is consistency at the top of management. There are times where a change in field management seems warranted. But the Phillies have the right manager for this team. What is not certain is if they have the right mix of players. And then, of course, there is the matter of being the hot team when it comes time for the playoffs.

Russ Walsh is a retired teacher, writer, baseball coach, and long-suffering Phillies fan, who writes for the Society for American Baseball Research and has recently begun posting his own newsletter about baseball history called The Faith of a Phillies Fan on Substack. You can reach him at ruswalsh@comcast.net.

Extra Innings: They Said It, We Didn’t

Did Rose’s death soften Manfred? Was the case presented to the commissioner by Rose’s lawyer and daughter singularly moving? Doubtful on both counts, considering Manfred’s resistance to reinstating Rose in the past. Only after Trump entered the picture did the commissioner do an about-face.

Manfred is nothing if not shrewd. He surely did not want to risk the president embarrassing him publicly on social media. He also likely did not want to get on Trump’s wrong side at a time when he is pushing for a direct-to-consumer streaming service for the league, and the migration from broadcast to streaming by professional sports leagues is under government scrutiny.

—Ken Rosenthal, The Athletic.

Apparently it’s OK to gamble on baseball now, even those involving your own team, while making a mockery out of the sport’s most sacred rule.

You want to cheat, lie, go to prison for tax evasion and be accused of statutory rape, hey, all is forgiven.

You learn in journalism school that you can’t libel the dead.

Who knew that once you’re dead, all could be forgiven too?

—Bob Nightengale, USA Today.

It’s a serious dark day for baseball. For my dad, it was all about defending the integrity of baseball. Now, without integrity, I believe the game of baseball, as we know it, will cease to exist . . . The basic principle that the game is built on, fair play, and that integrity is going to be compromised. And the fans are losers. I don’t know how a fan could go and watch a game knowing that what they’re seeing may not be real and fair anymore. That’s a really scary thought.

—Marcus Giamatti, actor/director/musician, and son of commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti, who banished Rose in 1989.