Pregame Pepper

. . . Bubbles Hargrave finished in a three-way tie for the 1926 National League batting championship—with two Reds teammates, Rube Bressler and Cuckoo Christensen . . . but a lack of formal, official batting title standards led to NL president John Heydler awarding Hargrave the title after the season despite each of the trio playing in fewer than 115 games each.

. . . Hall of Fame manager Casey Stengel once nicknamed Hall of Fame second baseman Billy Herman John the Baptist: His head is always on the plate, and he cons the umpires into calling perfect strikes too high.

Leading Off

The Hoosier Heights

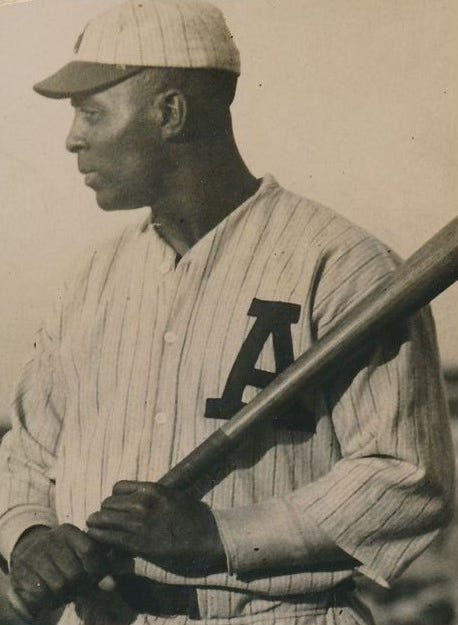

Hall of Famer Oscar Charleston is the best of Indiana’s starting nine.

By Chris Jensen

I had great fun coming up with all-time teams by players’ state of birth for my first book, Baseball State by State. However, that book came out in 2012, during Mike Trout’s rookie season, which is why he was only listed as a future star in the New Jersey chapter. I’ve wanted to do an updated version of the book, so I’ll start here by revisiting the Indiana all-time team, which includes those who played in the Negro Leagues:

Catcher—For catcher, Bubbles Hargrave prevails over Milt May. Hargrave batted over .300 six straight seasons, threw out 40.2 percent of base stealers and had a lifetime batting average of .310 with a 118 OPS+ compared to .263 and 93 for May. Plus, Bubbles is one of the all-time great nicknames.

First Base—I spent more time debating the all-time Hoosier first baseman battle between Don Mattingly and Gil Hodges than I did any other position for any state. I’m still not convinced it’s the right call, but I went with Donnie Baseball over Hodges.

Mattingly stood out with nine gold gloves, one MVP Award and a .307 lifetime average, compared to .273 average for Hodges. Hodges did have the edge in home runs (370 to 222), RBIs (1,274 to 1,099) and WAR (43.8 to 42.4), as well as two World Series titles, but his highest finish in the MVP balloting was seventh.

The deciding factor came down to the fact Mattingly was in the conversation to be called the best player in baseball for a four or five-year period, while Hodges was always a complementary player on some great Dodger teams.

Second Base—Hall of Famer Billy Herman is the logical choice at second base, after the ten-time All-Star batted .304 with 2,345 hits and accumulated 57.6 WAR. However, Frank (Weasel) Warfield was given strong consideration.

Playing with rage and fury for nineteen seasons in the Negro Leagues, Warfield was the best second baseman in the East during a playing career that lasted from 1914 to 1932. He batted .343 in his rookie season with the St. Louis Giants. His brilliant defensive play, daring baserunning, and sparkling play as a leadoff batter, was overshadowed by his dustups with opponents, umpires, and teammates.

Third Base—Scott Rolen has been enshrined in Cooperstown since my book came out, and he is the only noteworthy third baseman born in Indiana. He was named Rookie of the Year in 1997 and went on to win eight Gold Gloves for his sensational fielding at the hot corner. Rolen’s 316 home runs and .364 on-base percentage demonstrate he could and did beat you many different ways.

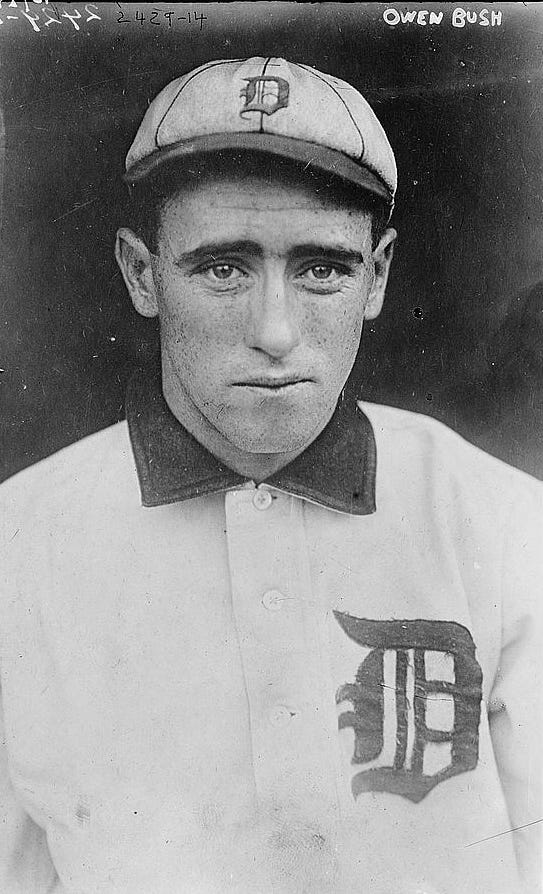

Shortstop—At shortstop, I went with Donie Bush, who excelled with the glove during the Ty Cobb era of the Tigers. Bush led American League shortstops in assists five times and putouts three times while also leading the league in walks five times. Honorable mention: Dickie Thon, who made one All-Star team during a 15-year career.

Outfield—Oscar Charleston is the greatest all-around player in the Negro Leagues, so he’s a no-brainer at one outfield spot. That leaves five Hall of Fame Hoosiers to choose from for the other two spots—not to mention Kenny Lofton, Cy Williams, and Negro League slugger Ted Strong.

I decided to stick with one original pick in Edd Roush, who batted .323 and won two batting titles. For the third outfield spot, I went back and forth about Lofton, who outpaced all the Hoosier outfielders except Charleston with 68.4 career wins above replacement-level (WAR).

Lofton batted .299 with 622 stolen bases, won four Gold Gloves, and made six All-Star teams. The deciding factor was Lofton’s seven seasons with at least 5.0 WAR, which indicates he had a bigger impact than the Hoosier Hall of Fame outfielders who proceeded him.

I gave Lofton the third outfield spot over original pick Max Carey. Carey ranks ninth all-time with 738 stolen bases, but his .285 average and 108 OPS+ demonstrate he was a notch below great. Sam Rice fell thirteen hits shy of 3,000 and batted .322 with six 200-hit seasons. However, Rice hit just 34 home runs despite playing mostly in the Live Ball Era, and his best season produced only 4.8 WAR. Nineteenth century star Sam Thompson averaged .331 but only had 1,988 career hits.

Chuck Klein capitalized on the cozy confines of the Baker Bowl to lead the league in homers four times, but he batted .353 in home games and .286 on the road. Underrated Strong averaged .323 for ten Negro League seasons with a 162 OPS+.

Designated Hitter—Ron Kittle gets the nod at designated hitter over Adam Lind. Kittle belted 176 home runs, but he was unable to duplicate his Rookie of the Year campaign in 1983 when he hit 35 homers and drove in 100 runs.

Hoosier Hurlers—Indiana has produced a number of exceptional right-handed starters including Babe Adams, Nig Cuppy, Dizzy Trout, Carl Erskine and Negro Leaguer Bill Holland. However, two Hall of Fame righties stood out for their achievements: Mordecai (Three Finger) Brown and Amos Rusie.

Rusie won 20 games in eight straight seasons from 1890 to 1898 and led the National League in strikeouts five times and ERA twice, on the way to 246 career wins. In the end, I stuck with Brown, who had a longer, more dominant career. Brown led the Cubs to four World Series (with two titles) in five seasons and posted a microscopic 1.06 ERA in 1906.

Tommy John is an easy choice for best left-handed starter. John won 288 games with a 3.34 ERA over a 26-year career. Art Nehf (184 wins) and Paul Splittorf (166 wins) are two other notable southpaws from Indiana.

For Indiana’s best relief pitcher, three-time All-Star Dan Plesac earns the nod with 158 saves and 1,064 appearances over 18 seasons. Ron Reed (103 saves, 3.46 ERA) and LaTroy Hawkins (127 saves, 1,042 appearances over 21 seasons) also received strong consideration.

The Skipper—Gil Hodges earns the selection as all-time Hoosier manager for leading the Miracle Mets to the 1969 World Series championship. Craig Counsell, Don Mattingly, Oscar Charleston, Frank Warfield, Donie Bush and Lloyd McClendon were other managers under consideration.

But Indiana’s all-time best player can only be Charleston, who remains underappreciated for his greatness.

Chris Jensen has written for Seamheads, Start Spreading the News, Elysian Fields Quarterly and the Yankees Annual Yearbook. He is the author of the recently released Baseball’s Two-Way Greats: Pitching/Batting Stars from Ruth and Rogan to Ohtani, as well as Baseball State By State. He can be contacted at chris.jensen81@hotmail.com.

Extra Innings: What They Said . . .

Oscar Charleston was Willie Mays before we knew who Willie Mays was.

—Buck O’Neil, Hall of Famer.

Did [manager Donie Bush] benching [Hall of Famer Kiki] Cuyler cost the Pirate the pennant? Obviously, it did not. Afterward, they went 34-18 and finished in first place . . . Did benching Cuyler cost the Pirates the [1927] World Series? Almost certainly not. The ‘27 Yankees were among the greatest teams ever; the ‘27 Pirates were not . . . Did trading Cuyler [after the ‘27 season] cost the Pirates any future pennants? Probably not. Cuyler remained a fine player, if less than wonderfully durable, through 1936. In all those years, the Pirates were competitive in only 1932 (four games out) and ‘33 (five).

—Rob Neyer, in Rob Neyer’s Big Book of Baseball Blunders.

His extraordinary baserunning talents inspired his nickname, Weasel Warfield, but the use of this nickname by the press was extremely rare during his lifetime. It first appeared in print in 1930, just two years before his death, and in the context of the nose-biting incident between Warfield and Marcell. Later, one sportswriter correctly stated that Warfield’s “pet name was ‘the weasel’ due to the fact that, like his namesake, he was cunning, brainy, and a strategist parexellence [sic].”—Margaret M. Gripshover, writing Warfield’s bio for the Society for American Baseball Research Bio Project.

To be honest with you, I thought he should have gotten in a few years ago. I was very happy for him. This guy is the ultimate professional, played the game the right way. As a manager, as a coach, you looked at guys like that, very few mental mistakes, always on top of his game. Played the game as hard as you could play for nine innings. There was really nothing Scott couldn’t do on the baseball field. He was a hitting machine, he drove in runs, hit lots of doubles, unbelievable third baseman. He had a tremendous pair of hands, a great arm. If he didn’t play a game, it was because he had an injury or something like that. This guy posted every day. His work ethic, off the charts. This guy was a tremendous baseball player.

—Larry Bowa, when Scott Rolen was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2023. The same Bowa who once ripped Rolen ten new ones, as the Phillies’ manager, in 2002, when Rolen called out the team’s then-upper management over empty promises about team improvements and a new ballpark. (Fans deserve a better commitment than this ownership is giving them, Rolen said.)