A Hall-of-Famer’s “Stunt Catch” Blows Up In His Face

A stunt turns into a great prank on a Hall of Fame manager Wilbert Robinson

IBWAA members love to write about baseball. So much so, we've decided to create our own newsletter about it! Subscribe to Here's the Pitch to expand your love of baseball, discover new voices, and support independent writing. Original content six days a week, straight to your inbox and straight from the hearts of baseball fans.

Pregame Pepper

Did you know…

. . . One of the first to fly in an airplane, Casey Stengel was a Kansas City native, born in July 1890. Roughly nine months previous, Smoky Joe Wood was born in Kansas City (though he would graduate high school in Colorado). Wood was a great example of how the “old school” handling of pitching arms burned out more of the elite players than it pushed into superstardom.

Wood made his Major League Baseball debut at age 18 and immediately was considered to have the best fastball in the game. No less than Ty Cobb considered Wood to have the fastest pitch that he ever faced. Wood’s 1912 was one of just 115 seasons in the history of the game where a pitcher recorded 10+ bWAR. Wood went 34-5 with a 1.91 ERA and 1.02 WHIP over 344 innings with 258 strikeouts, 35 complete games and 10 shutouts.

Unfortunately, Wood totaled 434 2/3 innings over six seasons after his amazing season, still producing tremendous numbers when he was on the mound, but too frequently dealing with a bum arm to consistently take his turn in the rotation.

Leading Off

A Hall-of-Famer’s “Stunt Catch” Blows Up In His Face

By Paul Jackson

In 1915, the Brooklyn Dodgers held their spring training camp in Daytona Beach, Florida, playing on a field named “Ebbets Field” in honor of the club’s president, Charles Ebbets. The team was mainly called the “Dodgers” by this point in history, but a new nickname would soon become popular: the “Robins,” a cap-tip to Brooklyn’s beloved manager, Wilbert Robinson.

Robinson was a living legend, a catching pioneer, and a former member of the famed National League Baltimore Orioles of the late 19th century. The 50-year-old manager was long-removed from his playing days, but still confident in his abilities in the spring of 1915, declaring he remained “the greatest pop-fly catcher in history.”

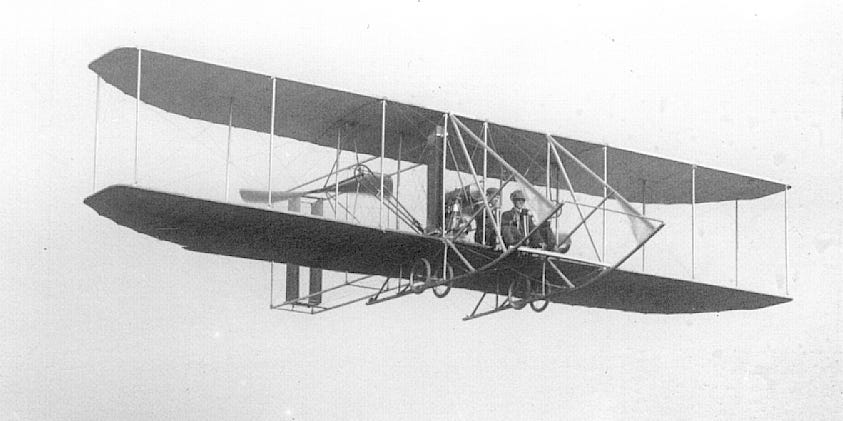

Near Daytona’s Ebbets Field sat the Hotel Clarendon, a white-glove beach resort that attracted wealthy snowbirds every winter. Along with its high-end amenities, the hotel partnered with professional aviators to offer three-minute “aeroplane excursions” over the beach and Atlantic Ocean, for the low-low price of $15 ($570 in today’s money). This was quite a perk in a year when fixed-wing aircraft had only existed for a decade, and there was just one kind of plane in commercial production: the Wright-Burgess Model B.

On their own dime, no ballplayer could afford to fly, but a wealthy booster in winter quarters nearby had kindly offered to cover the cost of any Dodger passenger. By mid-March, 18 players had reportedly flown, including Robinson. It was not for everyone, however, including 24-year-old infielder Casey Stengel, one of the team’s young stars. “I have flown many miles since then,” Stengel said in 1956, “but I wasn’t about to fly back there in a kite made out of a shirt material, pasted with glue and held together with wires.”

Making a different choice was the craft’s pilot, a pioneer aviator named Ruth Bancroft Law. Law received her piloting license in 1912, and just three years later she had a national reputation as a crack mechanic and a skilled and daring stunt flyer. Casey Stengel wouldn’t even sit on a glue-and-wire kite like the Model B, but Ruth Law would fly loop-the-loops in one, sitting and standing.

In March 1915, Law was the Clarendon’s pilot-in-residence. In between flying Dodgers, she also flew the owner of a local sporting goods store, who decided to use his $15 to get some free promotion. As Law flew him over Daytona Beach, he threw branded golf balls down into the sand below. Word of this stunt got back to the Dodgers practicing nearby, but Robinson was reported to be unimpressed, saying, “If somebody threw a baseball out of a plane, I bet I could catch it.” Somebody took that bet.

Local newspaper accounts also suggest some thinking that the ceremonial first pitch at upcoming official spring opening of Ebbets Field could be thrown from Law’s aeroplane. Charles Ebbets himself seems to have been toying with the idea of throwing the ball as Law flew him over the park.

Whether as test-subject or dare-actor, on March 13, with the team idled by wet weather, Robinson donned catching gear and prepared to make an attempt. The ball would be thrown by the team’s trainer, a man named Frank Kelly (or Kelley). During his complimentary flight, Kelly had reportedly felt quite comfortable, “climbing in the machine with all the nonchalance with which he would jerk a stiffened arm into condition.” Kelly was thrilled to get another trip, even after Law told him it would be the first time she’d ever flown in rain.

Law piloted her Wright-Burgess Model B to somewhere around 700 feet and banked to begin a run on the beach below. With the plane “roaring” overhead at approximately 45 miles an hour, Kelly tossed his cargo, which began a windblown descent. Robinson circled underneath, shouting for room and tracking the target as it grew larger in his vision. Various accounts have the object impacting Robinson’s arm, his wrist, his chest, or his stomach, but all agree it struck him and exploded in a mist of juice and pulp. It was a grapefruit.

How the expected baseball became a surprise grapefruit is unclear. Later accounts suggest a plot by some of the players to play a joke on Robinson (Stengel, the most famous member of that team, would come to be implicated), but 1915 accounts say that Kelly simply forgot to bring a baseball to the airfield, requiring some creative last-minute improvisation. All considered, we think it most likely that the grapefruit came from Ruth Law herself, by way of her mechanic, who rushed to find her something of comparable size to throw, perhaps taken from one of their lunches.

No one warned Robinson, however, and as what appeared to be blood and soft tissue splattered over his uniform, the confused manager briefly lost his cool, fearing he had been mortally wounded by a baseball. Various accounts have him expressing this sentiment in different ways, “I’m killed!” “I’m covered in blood!” and so on. But the best account--almost certainly apocryphal--has him declare, “Good God, it’s punctured my belly. There’s the grapefruit I had for breakfast!”

Once he realized his players were shrieking with laughter, Robinson gradually came to his senses. He was understandably upset when he found out what had happened, but the good joke had been a good lesson, learned the easy way. For the Dodgers’ spring opener, Ruth Law performed a flyover, but the ceremonial first pitch was thrown out by the city’s mayor, launched safely from the box seats next to the field

Paul Jackson writes about baseball, history, and culture on Substack at Project 3.18 and on Instagram. He has previously written for ESPN.com. Paul can be reached via email at pjacks2@gmail.com.

Extra Innings

By the end of the 1915 season, the Brooklyn club would have four future Hall of Famers on the team, with Robinson and Stengel both making enshrinement as a manager and Zack Wheat and Rube Marquard, a midseason acquisition, both making the Hall as a player.

Marquard would go on to post a 1.58 ERA over 205 innings in 1916 as Brooklyn made the World Series.