A Cooperstown Case for Dizzy Dismukes

Negro Leagues legend and a true jack of all baseball trades.

Pregame Pepper

. . . Dizzy Dismukes’s teammates for his 1915 no-hitter included Hall of Fame outfielder Oscar Charleston.

. . . The Indianapolis ABCs for whom Dismukes pitched the no-no were named for the initials of their original organiser, the American Brewing Company.

. . . Another ABCs teammate, second baseman Bingo DeMoss, eventually became the manager in the United States Baseball League—organised by Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey to scout black players for the Dodgers. The team DeMoss managed in the short-lived league: the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers.

Leading Off

Dizzy in Nickname Alone

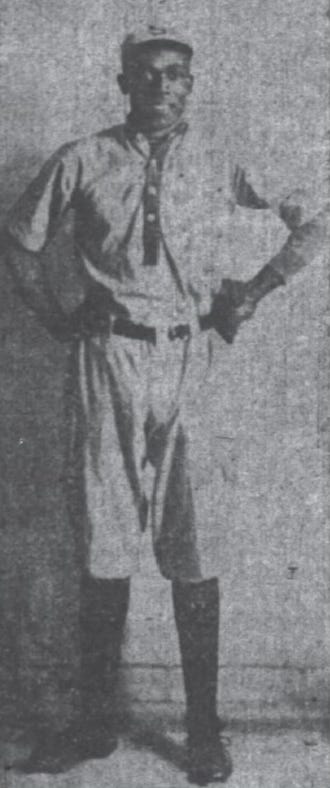

A Cooperstown case for Negro Leagues pitcher/jack-of-all-trades Dizzy Dismukes.

By Bill Johnson

In baseball, there is a demand for all manner of skill and experience. Only on the rarest occasions is such an array of talent found in a single person. One such savant was William (Dizzy) Dismukes.

He was a star pitcher, throwing a no-hitter against none other than Rube Foster’s 1915 Chicago American Giants, and tossing a four-hit complete-game against the 1911 Pittsburgh Pirates.

He spent parts of two decades as a manager credited with at least 196 career wins. He was the traveling secretary for the 1942 Kansas City Monarchs. He was a part-time baseball writer with the Pittsburgh Courier. He was even the secretary of the Negro National League for a time.

In the early 1950s, Dismukes became one of the first black scouts in organized baseball, working for both the Chicago White Sox and the New York Yankees. In 1952, in fact, the Courier listed him among the best Negro Leagues pitchers of all time.

All those make him one of the more important people inbaseball history. He’s been somewhat anonymous to the general public, but Dismukes richly deserves consideration and election to the Hall of Fame.

Born in 1890 in Birmingham, Alabama, Dismukes attended Talladega College, in Alabama, before taking up professional baseball. In 1908, at 17 years of age, he began his baseball career as a right-handed submarine-style pitcher for the East St. Louis Imperials.

His baseball skill and mercenary approach took him to the Kentucky Unions in 1909, and briefly to the Indianapolis ABCs, where he pitched against C.I. Taylor’s Birmingham Giants in a late July barnstorming series in Indiana. Dismukes then joined the powerful West Baden (Indiana) Sprudels.

It was with the Sprudels that the pitcher tossed what proved to be one of the most notable games of his career, the 1911 four-hitter in an exhibition against the Pirates on September 10. In a fitting postscript to the day, interim Pirates manager Bill Keen noted that he failed “to see anything humorous in defeat at the hands of a colored team . . .”

Dismukes returned to the C.I. Taylor-led ABCs in April 1915. In his non-barnstorming appearances, he is credited with a 14-5 record over 188 innings pitched that year, and in his second start with Indianapolis, he threw a no-hitter against Foster’s American Giants on May 9.

After a hitch in the Army, Dismukes returned to Dayton in 1919. Somewhere in his career, he was tagged with the nickname “Dizzy.” It was certainly an ironic moniker, as he was regarded as one of the more cerebral and calm players of the time.

Turning 30 years old in 1920, he logged 187 innings in the new Negro National League, and the team enjoyed a winning record on the season. Near the end of the 1921 season, he moved to the Pittsburgh Keystones as player-manager.

The 1922 season in Pittsburgh proved important in Dismukes’s career and life in that he was also invited to begin to contribute the occasional baseball column to the Courier, where he would opine on the state of the game, the level of play, and generally bridge the gap between newspaper-reading fans and the players on the field.

Dismukes would continue to write his columns for years, finally giving up the typewriter to work as a front-office executive for the Monarchs in the 1940s.

He returned to the ABCs in as player-manager in 1923, following the sudden death of mentor Taylor. After leading the team to a 51-33 record in 1923, but only a 5-21 mark in 1924, he left midseason to manage the Birmingham Black Barons. After a reported disagreement with Black Barons’ owner Joe Rush, however, he left again, and finished the year with the Homestead Grays.

Now a baseball nomad, Dismukes spent the next fifteen years pitching for, and managing, the Memphis Red Sox, the St. Louis Stars, the American Giants [after Foster’s sudden demise in 1930], the Columbus Blue Birds, the Black Barons, the Atlanta Black Crackers, and the Grays.

He was named to his final, interim managerial job with Kansas City after Newt Allen’s surprise resignation in 1942. Dismukes then moved into the role of the club’s traveling secretary when Frank Duncan took over as player-manager during that memorable campaign.

He remained with the Monarchs’ front office until 1953, when the Yankees offered him a job as a scout, focusing his search on the array of untapped talent that still existed in the Negro American League. The move was significant, in that the Yankees still had not fielded a black player eight years after Jackie Robinson broke the color line for the crosstown rival Brooklyn Dodgers.

The scouting job also proved to be the most lucrative in Dismukes’s career. He had never married, so the arduous lifestyle was fine with him, and the $10,000 per year that he earned certainly made the effort worthwhile.

Once the Yankees introduced Elston Howard as their first black big leaguer in 1955 and began to populate their minor-league system with talented minority players at all levels, Dismukes moved on. He scouted for the White Sox in 1956, and returned to the field in 1957, replacing Jelly Taylor as manager of the Monarchs. After the 1958 season, Dismukes hung up his spikes for good.

Over the next few years, his health began to falter, and on June 30, 1961, Dismukes passed away. He is buried at the Mount Hope Veterans Memorial Cemetery, in Campbell, Ohio. But a baseball legacy as all things to all people, and his extraordinary excellence in every role, make him very worthy of Cooperstown consideration and election by the Classic Baseball Era Committee in 2027.

Bill Johnson has contributed nearly 50 essays to SABR’s Biography Project, and presented papers at the 2011 Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, the 2017 and 2023 Jerry Malloy Negro League Conferences, and the inaugural Southern Negro League Conference. He has published a biography of Hal Trosky (McFarland and Co., 2017) and an article about Negro American League All-Star Art (Superman) Pennington in the journal Black Ball. He is on ‘X’: @bjohnson162.

Extra Innings: What He Said

The general public. feels that the Yankees are against Negro players, and that makes it tough for me. Just recently I had a good Negro prospect lined up but lost him. A scout from another team came along and signed the boy after his father told him that the Yankees didn’t really want Negro players . . . The people who have been critical of the Yankees have been most unfair. Just because they didn’t keep [first baseman Vic] Power and sent Howard to Toronto does not mean they are anti-Negro. I know that they are not adverse [sic] to Negro players. All they are looking for is the Yankee type of player, race or color does not matter.

—Dizzy Dismukes, as cited by legendary Pittsburgh Courier sportswriter Wendell Smith, September 1954.

Know Your Editors

HERE’S THE PITCH is published daily except Sundays and holidays. Benjamin Chase [gopherben@gmail.com] handles the Monday issue with Dan Freedman [dfreedman@lionsgate.com] editing Tuesday and Jeff Kallman [easyace1955@outlook.com] at the helm Wednesday and Thursday. Original editor Dan Schlossberg [ballauthor@gmail.com], does the weekend editions on Friday and Saturday. Former editor Elizabeth Muratore [nymfan97@gmail.com] is now co-director [with Benjamin Chase and Jonathan Becker] of the Internet Baseball Writers Association of America, which publishes this newsletter and the annual ACTA book of the same name. Readers are encouraged to contribute comments, articles, and letters to the editor. HtP reserves the right to edit for brevity, clarity, and good taste.

There was a team called the Atlanta Black Crackers. Wow!